#Hamlet and Ofelia

Text

Sarah Bernhardt (French, 1844-1923), Ofelia (or The Death of Ophelia), 1880, white marble, private collection, Normandy.

The author of this dignified sculpture is the worldwide known actress Sarah Bernhardt, who delighted in sculpting marble, when she did not act on the stages of half the world. She began by opening her own studio in 1873 and creating works also exhibited at the Paris Salon and in London, where she was equally famous as a theatrical actress. The most ferocious criticism that was moved on her life was that she used to work on her sculptures dressed in a white pantsuit, clothing considered scandalous for a woman of the late 1800’s (the painter Rosa Bonheur had to ask for a special permission to go to the horse fairs wearing pants, not to dirty the long clothes).

The sculpture is a high relief depicting Ophelia, with her head turned to the side and eyes closed. She only wears a wreath of flowers on her head that goes down to partially cover her bare breasts. She seems to float on the water that moves her hair but, soon, poor Ofelia will drown (famous the painting by John Everett Millais, whose model was Elisabeth Siddal, future wife of Dante Gabriel Rossetti). Only in 1886, 6 years after the realization of this sculpture, did Bernhardt finally receive the honor of reciting in Hamlet, but she didn''t play the female role of Ophelia, but the male role of the protagonist Hamlet.

Once finished, Sarah Bernhardt took her high relief on tour in the United States, unwilling to part with her, and she presented it at the 1881 Paris Salon, where she received an honorable mention from the jury.

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ofelia" por John Everett Millais [1851/1852]

#art#arte#john everett millais#18th century#siglo xviii#obras#hamlet#william sheakespeare#sheakspeare#museum#museums#pre raphaelism#ofelia

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honremos la primer publicación con un personaje shakesperiano icónico en el mundo del arte, Ofelia...

Gertrude

"There is a willow grows askaunt the brook,

That shows his hoary leaves in the glassy stream,

Therewith fantastic garlands did she make

Of crow-flowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,

But our cull-cold maids do dead men’s fingers call them.

There on the pendant boughs her crownet weeds

Clamb’ring to hang, an envious sliver broke,

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And mermaid-like awhile they bore her up,

Which time she chaunted snatches of old lauds,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element. But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull’d the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death."

Gertrudis

"Donde hallaréis un sauce que crece a las orillas de ese arroyo, repitiendo en las ondas cristalinas la imagen de sus hojas pálidas. Allí se encaminó, ridículamente coronada de ranúnculos, ortigas, margaritas y luengas flores purpúreas, que entre los sencillos labradores se reconocen bajo una denominación grosera, y las modestas doncellas llaman, dedos de muerto. Llegada que fue, se quitó la guirnalda, y queriendo subir a suspenderla de los pendientes ramos; se troncha un vástago envidioso, y caen al torrente fatal, ella y todos sus adornos rústicos. Las ropas huecas y extendidas la llevaron un rato sobre las aguas, semejante a una sirena, y en tanto iba cantando pedazos de tonadas antiguas, como ignorante de su desgracia, o como criada y nacida en aquel elemento. Pero no era posible que así durarse por mucho espacio. Las vestiduras, pesadas ya con el agua que absorbían la arrebataron a la infeliz; interrumpiendo su canto dulcísimo, la muerte, llena de angustias."

1) John William Waterhouse – Ophelia, 1910

2) John William Waterhouse – Ophelia, 1894

3) Joseph Kirkpatrick – Ophelia, 1896

4) Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret - Ophelia

5) Arthur Hugues - Ophelia

6) Paul Albert Steck – Ophelia, 1895

7) Thomas Francis Dicksee - Ophelia

PARTE 1

#art#traditional art#19th century art#art details#british art#fine art#traditional painting#tragedy#shakespeare#hamlet#john william waterhouse#joseph kirkpatrick#arthur hughes#paul albert steck#thomas francis dicksee#waterhose#dicksee#ophelia#ofelia

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

[ID: thumbnail is a drawing of a dog curled up on itself, asleep. /id]

Ofelia by Kiltro

(It's a light, it's a light, it's a light, it's a light)

(It's a light, it's a light, it's a light)

It's a light, it's a light, it's a light, it's a light

It's a light, it's a light, it's a light, it's a light, it's a light

Think of a lot of things in the nights, you know?

I never sleep when you're gone

Caught in my obstinance

It's curious, what still keeps me up

It′s a soliloquy

Is there truly no one listening?

Do I run?

Stick here for life, I don't write

I needed more

Oh, easy come, easy go

Take it all from me

Easy come, easy go

Take it all from me

I think quite a lot of us in the nights, you know?

I never fuss when you leave

For all of my obstinance

It′s penitence, I act as you seem

I love like a smoking gun

Ripped a shot, then I hid and run from thе scene

You're sick of your lifе, I don't lie

The ones you need

Oh, easy come, easy go

Take it all from me

Easy come, easy go

You take it all from me

Easy come, easy go

Take away the wine? please

Easy come, easy go

You take them all from me

Said you love to think that I don′t know your reasons anymore

You said you love to think that I don′t know your reasons anymore

And I could disregard the nights like this you're never at the door

You sent me a ride, how am I? I needed more

Ofelia

Ofelia

Loves you so

Loves you so

Ofelia

Ofelia

Loves you so

It's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright

It's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright, it's alright

It's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie

It's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie

It's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie, it's a lie

#kiltro#ofelia kiltro#ophelia#hamlet#shakespeare#video#music#lyrics#This has been in my head a LOT this month#because of#social shakespeare#Youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ophelia#Amleto#Hamlet#ofelia#ophelia aesthetic#ofelia aesthetic#william shakespeare#litterature#british literature#letteratura#writing#write#writer#scrivere#scrittore#scrittura

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ofelia

Moise Kisling

Lithograph on paper, 1952

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

We can understand the expression of the slow heart in love with its maiden.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

my eyes are open

#Aged up I can see it#NEVER heard of this ship but I'm so down#Genuinely can't remember how old Nellie was. If she was legit just-turned 18 and ferrying these children around. Or she was 21.#21? ehhhh#listen we can just hand-wave Jonah into being 21 too. Fuck it.#Jonellie#They could do a rap of Hamlet; playing Hamlet and Ofelia and I think that would be a great bonding experience.

0 notes

Text

A Rundown on the Absolute Chaos that is First Quarto Hamlet

IMPORTANT UPDATE: This post may be getting a revamp with better citations—my cross-checking source was scrubbed from the internet entirely???

I said I was going to sleep before writing this. I did not. Here it goes anyway!

TL;DR: Multiple versions of Hamlet were printed between 1603 and 1623. Across these multiple texts, we get some fairly major differences in characterization and plot disparities. The First Quarto is most infamous for its oddness- which includes shockingly brief soliloquies, mother-son bonding, wild spellings of everyone’s names, and deleted/adapted scenes with major plot/character implications.

A full (long!) rundown is below the cut, including sources, transcribed Q1 content and lore, further Hamlet lore, and my fan theories! Feel free to skip the bits you don’t care about, I got way too into this.

Note: *I have updated these lines to their modern spellings for ease of reading

What is the First Quarto? What’s a “quarto”? Who wrote this?!

All pressing questions, my dear dedicated fan of William Shakespeare’s hit play Hamlet!

The First Quarto was published in 1603 and was (presumably, as implied by the name) printed as a quarto (a little book created by folding printed pages into four leaves- eight pages). It is much shorter than the later publications and is presumed to be transcribed from memory by an actor (probably the guy who played Marcellus), who may have been a member of a touring troop of actors performing the play.

Q1 is not necessarily considered a first draft of the play, but something of a “pirated” (by memory) copy that was later amended by Q2 and F1.

Are you saying that Hamlet comes with the stageplay equivalent of a “deleted scenes and extra credits” movie disc?

Yes! And not just one, but many: Quartos 1-5, the First Folio, multiple foreign language versions, and more! Your typical modern copy of Hamlet is a combination of the Second Quarto and First Folio.

Q2 (published in 1604 or 1605) is considered more “Shakespeare-accurate” than Q1- it seems to be a manuscript actually written by Shakespeare combined with an edited version of Q1′s Act 1 text rather than just some guy’s memory of the play. F1 was published much later (1623) and is some combination of another playhouse manuscript and possibly Q2 (but which—Q2 or the manuscript—had more influence in the creation of F1 is unclear). Q2 and F1 have tons of differences in wording and each has some content that the other doesn’t, but what you need to know here is that a typical modern script is an F1/Q2 combo (because editors didn’t think the public would want like six different scripts- fair enough.)

Quartos 3-5 are slightly edited versions of Q2. There seem to be a few other versions in different languages (like the German version) which share points from a variety of the above sources.

So... Q1? How is it any different from the version we all know (and love, of course)? What do the differences mean for the plot?

We’ll start with minor differences and build up to the big ones.

First of all, the language! Everything is spelled to the discretion of the transcriber, which produces gems such as “for England hoe.”

These spelling differences also extend to the characters! Laertes is “Leartes”, Ophelia is “Ofelia”, Gertrude is “Gertred” (or sometimes “Gerterd”), Rosencrantz is “Rossencraft”, Guildenstern is “Gilderstone”, and my favorite, Polonius gets a completely different name: Corambis.

(This goes on for minor characters, too. Sentinel Barnardo is “Bernardo”, Prince Fortinbras of Norway is “Fortenbrasse”, Voltemand and Cornelius- the Danish ambassadors to Norway- are “Voltemar” and “Cornelia” (genderbent Cornelius?/hj), Osric doesn’t even get a name- he is called “the Bragart Gentleman”, the Gravediggers are called clowns, and Reynaldo (Polonius’s spy) gets a whole different name- “Montano”.)

The stage directions include more detail! Ex: Ophelia enters in Act 4 with a lute to play along to her song of insanity. (*Enter Ofelia, playing on a lute, and her hair down, singing). (Some bits are missing direction though! In Act 3, when Hamlet calls upon Horatio to watch Claudius on the night of the play, there is no instruction for Horatio to enter the scene. He appears without being asked.)

There is a slight reordering of scenes in Act 3. Claudius and Polonius go through with the plan to have Ophelia break up with Hamlet immediately after they make it (typically, the plan is made in early II.ii and gone through with in III.i, with the players showing up and reciting Hecuba between the two events). In this version, the player scene (and Hamlet’s conversation with Polonius) happen after ‘to be or not to be’ and ‘get thee to a nunnery.’ I’m not sure if this makes more or less sense. Either way, it has minimal impact on the story.

Many lines, especially after Act 1 are considerably altered or shortened. Everyone is a lot more straightforward and (sometimes) a lot less iambic pentameter-y and poetic. A few examples: Laertes’ usually long-winded I.iii lecture on love to Ophelia is shortened to just ten lines (as opposed to the typical 40+). Polonius (er... Corambis) is still annoying and incapable of brevity, but less so than usual. His lecture on love is also cut significantly! Hamlet’s usual assailing of Danish drinking customs (I.iv) is cut off by the ghost’s arrival. He’s still the most talkative character, but his lines are almost entirely different in some monologues, including ‘to be or not to be’! In other spots, however, (ex: get thee to a nunnery!) the lines are near-identical. There doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to where things diverge linguistically.

And then the big differences: the additional scene and Gertrude’s promise to aid Hamlet in taking revenge. Act 3, scene 4 goes about the same as usual with one major difference: Hamlet finishes off not with his usual declaration that he’s to be sent for England but with an absolutely heart-wrenching callback to act 1, in which he echoes the ghost’s lines and pleads his mother to aid him in revenge. And she agrees. Here is that adapted scene (without line breaks for some reason- ah, formatting!):

*Gertrude: Alas, it is the weakness of thy brain which makes thy tongue blazon thy heart’s grief: but as I have a soul, I swear by heaven, I never knew if this most horrid murder: but Hamlet, this is only fantasy, and for my love forget these idle fits.

Hamlet: Idle, no mother, my pulse does beat like yours, it is not madness that possesses Hamlet. O mother, if you ever did my dear father love, forbear the adulterous bed to-night and sun your self by little as you may, in time it may be you will loathe him quite and mother, but assist me in my revenge and in his death, your infamy shall die.

Gertrude: Hamlet, I swear by that majesty that knows our thoughts and looks into our hearts, I will conceal, consent, and do my best what stratagem so ever thou shalt devise.

Hamlet: It is enough mother, good night. [to polonius] I’ll provide for you a grave who was in life a foolish and prating knave.

*exit Hamlet with Polonius’s body*

Despite having seemingly major consequences for the plot, this is never discussed again. Gertrude tells Claudius in the next scene that it was Hamlet who killed Polonius (Corambis, whatever!), seemingly betraying her promise.

However, Gertrude’s admission of Hamlet’s guilt (and thus, betrayal) could come down to the circumstance she finds herself in as the next scene begins. There is no stage direction denoting her exit, so the entrance of Claudius in scene 5 may be into her room, where he would find her beside a puddle of blood, evidence of the murder. There’s no talking your way out of that one…

And now the most drastic change: the bonus scene. After IV.vi (act 4, scene 6), (but before IV.vii) comes this scene*, in which Horatio informs Gertrude that Hamlet was to be executed in England but escaped. Here it is with modern spellings but without line breaks (man, I hate formatting things!)

Enter Horatio & Gertrude

Horatio: Madam, your son is safe arrive’d in Denmark. This letter I even now received of him, whereas he writes how he escaped the danger and subtle treason that the king had plotted, being crossed by the contention of the winds, he found the packet (letter) sent to the king of England, wherein he saw himself betray’d to death, as at his next conversion with your grace, he will relate the circumstance at full.

Gertrude: Then I perceive there’s treason in his looks that seemed to sugar o’re his villainy: but I will sooth and please him for a time for murderous minds are always jealous. But know not you, Horatio, where he is?

Horatio: Yes, madam, and he hath appointed me to meet him on the east side of the city to-morrow morning.

Gertrude: O, fail not, good Horatio, and commend me a mother’s care to him, bid him a while be wary of his presence, lest that he fail in that he goes about.

Horatio: Madam, never make doubt if that: I think by this news be come to court: he is arrive’d, observe the king and you shall quickly find, Hamlet being here, things fell not to his mind.

Gertrude: But what became of Guilderstone and Rossencraft?

Horatio: He being set ashore, they went for England and in the packet there writ down that doom to be performed on them pointed for him: and by great chance he had his father’s seal, so all was done without discovery.

Gertrude: Thanks be to heaven for blessing of the prince, Horatio, I once again take my leave, with thousand mother’s blessings to my son.

Horatio: Madam, adieu.

If Gertrude knows of Claudius’s treachery (”there’s treason in his looks”), her death at the end of the play does not look like much of an accident. She is aware that Claudius killed her husband and is actively trying to kill her son and she still drinks the wine meant for Hamlet!

Now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for! My thoughts! Yippee!

Clearly, my favorite gift this Christmas was my copy of The Riverside Shakespeare, gifted to me by my grandma. I don’t think I’ll ever sleep again now that reading this is an option. (This play has me head-over-heels, goddamn!)

Anyway, here are my thoughts on Q1 (as abridged as I can get them, seeing as this post is already nearly 2,000 words long.)

On Gertrude: WOW! I’m convinced that she is done dirty by First Folio and Q2! She and Hamlet have a much better relationship (Gertrude genuinely worries about his well-being throughout the play.) She has an actual personality that is tied into her role in the story and as a mother. I love Q1 Gertrude even though in the end, there’s nothing she can do to save Hamlet from being found out in the murder of Polonius and eventually dying in the duel. Her drinking the poisoned wine seems like an act of desperation (or sacrifice? she never asks hamlet to drink!) rather than an accident.

On the language: I think Q1′s biggest shortcoming is its comparatively simplistic language, especially in ‘to be or not to be’*: (again with the formatting!)

Hamlet: To be, or not to be, aye, there's the point. To die, to sleep, is that all? Aye, all: no, to sleep, to dream, aye, merry there it goes. For in that dream of death, when we awake, and borne before an everlasting judge, from whence no passenger ever returned, the undiscovered country, at whose sight the happy smile, and the accursed damn'd. But for this, the joyful hope of this, who’d bear the scorns and flattery of the world, scorned by the right rich, the rich cursed of the poor? The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd, the taste of hunger, or a tyrants reign, and thousand more calamities besides, to grunt and sweat under this weary life, when that he may his full quietus make, with a bare bodkin, who would this endure, but for a hope of something after death? Which puzzles the brain, and doth confound the sense, which makes us rather bear those evils we have, than fly to others that we know not of. Aye that, O this conscience makes cowards of us all.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s good, but it doesn’t feel quite complete, which makes sense for Q1- that’s the vibe I get overall from this version: it’s Hamlet at an earlier point in the play’s journey to becoming its modern renditions and compilations.

On the ending: The ending suffers from the same effect ‘to be or not to be’ does- it is simpler and (imo) lacks some of the emotion that F1 later emphasizes. Hamlet’s final speech is significantly cut down and Horatio’s last lines aren’t quite so potent- although they’re still sweet!

*Horatio, to Fortinbras and co.: Content yourselves, I’ll show to all, the ground, the first beginning of this Tragedy: Let there a scaffold be reared up in the marketplace, and let the State of the world be there: where you shall hear such a sad story told that never mortal man could more unfold.

Horatio generally is a more active character in Q1 Hamlet. This ending suits his character here: He will tell Hamlet’s story, tragic as it may be. It reminds me a bit of We Raise Our Cups from Hadestown.

Overall, I loved reading this version and highly encourage you to do the same! (Two PDFs are linked below!) The spelling is hard to overlook at times, but if you can get through it, this is a fascinating interpretation of the same Hamlet we love and it’s worth a read! There’s so much more I want to get into but I absolutely must sleep, so adieu for now!

And finally, my sources:

The Riverside Shakespeare (pub. Houghton Mifflin Company; G.B. Evans, et al.)

Q1 PDF (Internet Shakespeare) https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1/complete/index.html

***THIS SOURCE NO LONGER EXISTS.*** Q1 PDF (STF Theatre) https://stf-theatre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/HAMLET-%E2%80%93-the-1st-Quarto.pdf (cross-reference for lines)

#Hamlet#shakespeare#first quarto hamlet#oh man i am tired#definitely entered my unhinged college student era#classical literature#you will be the death of me!#this will be edited for clarity and punctuation later

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

just encountered first quarto hamlet for the first time in, apparently, my life, and what the fuck. we got queen gertred. we got ofelia and leartes and their dad corambis. and how could I forget that magnificent comedy duo, rossencraft and gilderstone! this is what happens when you order shakespeare off wish dot com

#hamlet#yeah yeah yeah spelling was loosey goosey and Shakespearean canon is the result of 400 years of editorializing#but CORAMBIS…

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

chapter II: ophelia and hamlet

/extract/

Oh Ofelia, the first time I watched you cry as I was the cause of it, I loved it, the gut wrenching feeling in my stomach made me crave more for it, I wanted to make you emit those sounds from your mouth again, and it didn't matter if they were of pleasure or pain.

I'm deeply sorry for all the trouble I've caused you, but a man like me craving flesh and bones like yours, couldn't help himself.

Oh dear Ofelia, how I wish I was you, to be inside you, to taste you and to devour you whole.

I loved you,

I really did,

In my own twisted way anyways.

#felix catton#felix catton x reader#wattpad#felix catton x reader x oliver quick#oliver quick#saltburn

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP (Re)Intro: Hamish

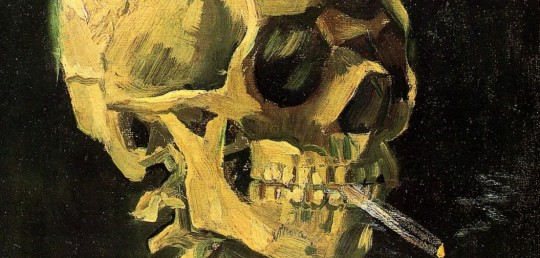

(Image ID: A cropped slice of Van Gogh's Skull with Burning Cigarette focusing on the facial structure.)

Genre: Literary Fiction/Gothic | Progress: Rewriting | World: Earth | POV: First Person Referral (I to You), Past Tense | Hamlet Retelling

Summary

Hamish Herbert Jr. is the son of Hamish Herbert Sr. and Genoveva Machado de Herbert, two prominent politicians, and all he wants to do is abandon his past. Horacio Aiza is a bright university student looking to leave his abusive childhood behind. Their codependent friendship leads them to Hamish's family home upon news of Hamish Sr.'s death. But once they arrive, Hamish and Horacio are haunted by both real and metaphorical ghosts as they attempt to uncover the truth. A Hamlet retelling.

In One Sentence

Upon the news of Hamish's father's death, Horacio accompanies him back to his abusive family, where both of their haunting pasts are just as dangerous as the present.

Literal Logline

"Ride or die" in the most literal sense, featuring ghosts.

Inspirations

Warsan Shire's poetry, NBC's Hannibal, Fransisco Goya's black paintings, "From Now On We Are Enemies" by Fall Out Boy, The Secret History by Donna Tartt

Why am I rewriting it?

Put quite simply, Hamish was my first novel that I took some real risks with. Looking back at the last draft (from 2020, before I was even a man), I can fully identify that many of my literary hallmarks were established in this novel. It was a test of my ability to write unlikable, morally-gray characters in a way that didn't have to be fully-explained, and with little satire, unlike Jeez Take the Wheel. It was the first novel I posted to my writing Insta, so it has some great nostalgia for me. And it feels right to return to now that I've established myself as an author of semi-gothic stories with plenty of fabulism. I feel like now I can elevate Hamish to a level I didn't achieve before, now that my skills are more mature.

Characters

Hamish Herbert Jr. (you) is a neurotic mess of a man, plagued by PTSD and his own dark thoughts. Eccentric, fascinating, and full of philosophic musings on every facet of life, Hamish is the manic pixie dream boy of his own life.

Horacio Aiza (I) is equally as riddled with PTSD, but chooses to focus instead on Hamish's issues than on solving his own problems. Quiet and reserved, he tempers Hamish's more emotional side while also providing the narration for the story. His nostalgia makes every moment bittersweet.

Genoveva Machado de Herbert is Hamish's mother. She is a stern, no-nonsense woman who cares more about her chances of being reelected for governor than her son.

Hamish Herbert Sr. is dead.

Claude Herbert is Hamish's uncle, along with being Genoveva's accomplice and lover. Though once loved, he is now just as cruel as both of his parents.

Pol Bello is Genoveva's lawyer, friend, and accomplice. He believes himself to be more important than he is.

Ofelia Bello is Hamish's ex-girlfriend. Enigmatic and brilliant, she becomes an ally to Horacio, though she does not seem to have good luck.

Leon Bello is Hamish's ex-boyfriend. He highly distrusts Hamish for cheating on his sister (with him) and has inherited Pol's self-importance.

Playlist

"From Now On We Are Enemies" - Fall Out Boy

Dirty Laundry - Bitter:Sweet

Archive - Mal Blum

Grave Digger - Matt Maeson

Wait - The Dear Hunter

Mama's Gun - Glass Animals

Domestic Bliss - Glass Animals

Excerpt

You scraped your ragged fingernails against my skin, the places where the curling script rested on your own ribs. This is where love comes to die. You’d gotten it, you said, when you were high, when you were sad, when you were remembering what you shouldn’t. I’ve always loved that poem, you said, and now it’s with me forever. “My father— I don’t know how I’m supposed to handle it all.”

Taglist

Ask to be tagged! I'll hopefully be making a few posts about this project.

#wip intro#wip#current wip#writers of tumblr#my writing#writing community#writeblr#writing blog#gothic literature#literary fiction#hamlet#hamish

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ofelia en el arte, parte 2.

Hamlet

I loved Ophelia. Forty thousand brothers

Could not with all their quantity of love

Make up my sum. What wilt thou do for her?

Hamlet

Yo amé a Ofelia como cuatro mil hermanos no hubieran podido hacerlo con todo su amor. ¿Qué quieres hacer por ella?

Friedrich Wilhelm Theodor Heyser - Ophelia

John Everett Millais - Ophelia, 1852

Constantin Meunier - Ophelia

Alexandre Cabanel - Ophelia, 1883

John William Waterhouse - Ophelia

#art#traditional art#19th century art#art details#british art#fine art#traditional painting#tragedy#shakespeare#hamlet#ophelia#ofelia#friedrich heyser#john everett millais#constantin meunier#alexandre cabanel#john william waterhouse#pre raphaelite

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey ! Thank you for all those polls !

Here are a few characters for already submitted names :

Augustus the shop keeper - Disney Fairies

Richter - Lilo and Stitch, the series

Here are a few other characters for other names :

Liesel Meminger - The Book Thief

Liesl Von Trapp- The Sound of Music

Liesel Van Helsing - Grimm

Liesel - World Flipper

Liesel - Legend of the Cryptids

Ofelia - Pan's Labyrinth

Ophelia - Hamlet

Ophelia Ramirez - Juniper Lee

Zelda Heap - Septimus Heap

Princess Zelda - Legend of Zelda

Zelda Spellman - Sabrina the Teenage Witch

Zelda - The Sandman

Angus MacGyver - MacGyver

Angus - Devil May Cry

Angus - Brave

Thank you for the suggestions!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here we see the Italian bass Nazzareno de Angelis (1881 – 1962) as King Henry from Lohengrin. I love the imposing costume and regal pose.

De Angelis was born at L’Aquila on 17 November, 1881 and began his musical life as a boy soprano, first with local choirs, then at the Capella Sistina in the Vatican. After his voice lowered, he studied with one Dr. Faberi at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome. For several years, he and his mentors wondered about his true vocal placement, and he studied both baritone and bass scores with equal intensity. The top of his voice was tremendous, but it became increasingly clear that it was centred where kings, prophets and devils live. His last two years at the Accademia were spent developing repertoire, and he gave several recitals there before making his opera début at the Comunale of L’Aquila in May of 1903 in Linda di Chamounix, followed by an opera called“L’Educate di Sorrento, by E. Usiglio, at the same theatre.

Hearing of his enormous success the management of Rome’s Teatro Quirino immediately engaged him, and, in early July, he débuted in Norma. He subsequently appeared at the Teatro Adriano as Il Spettro in Hamlet, to the Ofelia of Maria Barrientos and the Hamlet of Battistini, followed by Rigoletto and Tosi Orsini’s Yanthis. In 1904, after some twelve performances of La Gioconda at the Teatro Lirico of Milan, he appeared at Santa Maria Capua Vetere as Colline and at the Quirino in La Favorita, Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Basilio), Carmen (Zuniga), Ernani, Norma and Rigoletto. Carlo Galeffi was his Rigoletto in several performances. He toured the Netherlands from December of 1904 to May of 1905, singing such diverse roles as Dr. Grenvil in La Traviata, Zuniga in Carmen, Sparafucile in Rigoletto, Ferrando in Il Trovatore, Fouquier-Tinville in Andrea Chénier, Tom in Un Ballo in Maschera, Angelotti in Tosca, Basilio and Raimondo in Lucia di Lammermoor. The company gave performances in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague.

In the Autumn of 1905 he appeared at Mirandola in La Gioconda, at Parma’s Teatro Reinach in Rigoletto and Faust, and at Cagliari’s Teatro Regina Margherita as Alvise, along with those first historic performances of Mefistofele. Gaspare Nello Vetro’s Teatro Reinach says of his Faust Mefistofele: “The young Nazzareno De Angelis, now at the outset of his career, received the greatest applause and had to repeat ‘Dio dell’ Or’ at every performance.” At Cagliari, after his first performance of Boito’s Devil, the applause was interminable and it immediately led to a contract at Bari’s very important Teatro Petruzzelli, where he added Lohengrin and Iris to his roster of operas.

In the Spring of 1906 he left on his first South American tour, appearing at Santiago de Chile and Valparaiso from June to November. He sang nine roles to enormous success. On 16 August, the region was stunned by an earthquake so severe that performances had to be suspended until 1 September. The opera house at Valparaiso was almost completely destroyed, and it was there that the greatest damage occurred. Hundreds of people died, and the wounded numbered in the thousands. Despite recurring after-shocks, the season eventually returned to normal and, in addition to his scheduled performances, he participated in several hastily arranged benefits for earthquake victims. Among his new assignments were Ludovico to the commanding Otello of Antonio Paoli, and Marcel in Gli Ugonotti. His receptions were increasingly enthusiastic, and, before the season ended, he happily agreed to return. That agreement was honoured in both 1908 and 1909. El Mercurio said of him: “…. at the end of the Prologue to Mefistofele, De Angelis received a huge and most sincere ovation.” A later review stated that “he has reminded us again as Mefistofele how superb an artist he is, and in Germania has made us marvel at his versatility in this new role”.

The 1908 season saw him in eight operas including Gli Ugonotti with Hariclea Darclee, and in 1909, he sang nine roles including the creator part of Aquilante in Gloria After his appearances at Santiago, he is thought to have sung in Buenos Aires at the Teatro Coliseo, but no details have been unearthed about his roles during that engagement. He returned to the South American continent in 1910, 11, 12, 14, 19 and 1926, and he appeared in Buenos Aires, Rosario, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro and São Paolo. He sang Mefistofele in every theatre at which he appeared, and in every season, except for 1914. The list of operas he performed in South America only is long: Tannhäuser, La Sonnambula, I Puritani, Gomes’s Il Guarany and Salvator Rosa, Galitsky in Prince Igor (his only Russian opera, though sung in Italian), Les Huguenots (also in Italian), de Campos’s Um Caso Singular, Verdi’s Otello and Franchetti’s Germania.

On 15 January, 1907 he débuted at La Scala as Alvise in La Gioconda and appeared for the first time in Tristan und Isolde, La Wally and as Aquilante de Bardi in the world premiere of Cilea’s Gloria. Despite recurring arguments with the theater’s management, including one four year hiatus, he would sing twenty four roles over twelve seasons. The year offered two other very important debuts, Alvise at the Teatro Verdi of Firenze with Eugenia Burzio, and King Marke at Bologna’s Teatro Comunale with Amelia Pinto, Giuseppe Borgatti and Giuseppe Pacini. Tristan und Isolde received fifteen performances and was followed by De Angelis’ only appearances in Tschaikovsky’s Iolanthe.

1908 brought with it the beginning of his Scala partnership with Ester Mazzoleni. They first appeared in Franchetti’s Cristoforo Colombo conducted by Toscanini in a run of 16 performances, followed by a revival of La Forza del Destino. Mazzoleni described the event:

You will not be able to imagine what happened on that opening night. Icilio Calleja started ‘O tu che in seno agli angeli’ both too soon and out of tune, at which point all hell broke loose in the house. The theatre took on the atmosphere of a bullring, and, as often happens when things are not going well, the audience vented its rage at everything in sight. Both Pasquale Amato and Luisa Garibaldi were booed and hissed without mercy. The only ones who escaped their fury were De Angelis and myself. At the end, after almost collapsing from nervous exhaustion, we received a standing ovation. Notwithstanding our personal success, Toscanini, eyes ablaze, cancelled the remaining performances.

On 19 December, 1908 De Angelis and Mazzoleni appeared in the historic production of Spontini’s La Vestale, a revival that was repeated 16 times, and then travelled to Paris. Verdi’s I Vespri Siciliani was next in the list of successes, and, on 30 December, 1909, they caused a sensation in Cherubini’s Medea. In March 1910, they appeared in what was to be their last opera together, Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine. This unbroken string of personal triumphs is one of the most legendary of all stories associated with the Milan theatre. Among other memorable evenings at La Scala was the world première of Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei Tre Re on 10 April, 1913 in the role of Archibaldo, which he later premièred at the Colón of Buenos Aires, the Costanzi of Rome, Rio de Janeiro, São Paolo and Trieste’s Teatro Verdi.

Of his Archibaldo in the Rome première of L’Amore dei Tre Re, Il Tempo, on 15 March, 1919, said: “De Angelis, the old lion, he of the pungent, powerful voice, sang the ideal performance of Montemezzi’s king.”

Most of 1910 was spent in the Western Hemisphere. On 31 May De Angelis debuted at Buenos Aires’ Teatro del Opera in Lohengrin with Salomea Krusceniski, Luisa Garibaldi, Dygas and Riccardo Stracciari ,and he completed his season in Aida with Giannina Russ, Garibaldi, and Giovanni Zenatello, Norma with Russ, Garibaldi and Dygas, Mefistofele with Krusceniski and Dmitri Smirnov and Gotterdammerung with Krusceniski and Dygas. In August, the company visited Montevideo for a three week season. after which De Angelis traveled to Chicago for his only performances in the United States.

On 3 November, 1910 he sang in the inaugural performance of the Chicago Civic Opera Company as Ramfis. The cast included Karolewicz, de Cisneros, Bassi, Sammarco and Dufranne. He subsequently sang Colline in La Boheme with John McCormack, Raimondo in Lucia di Lammermoor and Ashby in La Fanciulla del West. On 18 January 1911, in a closing night gala, he appeared as Ashby with Carolina White, Caruso and Sammarco. It is curious that De Angelis accepted a contract with Chicago for roles so small when he had already become the most important bass at La Scala and in many of South America’s theatres. Perhaps the heady company that he would be keeping attracted him; that, with the hope that other more important roles would come his way. He visited several other cities, but, outside of a single appearance in Fanciulla del West at Milwaukee in November.

Upon his return to Italy, De Angelis prepared for the most important début of his career: the Costanzi of Rome. The theatre was to present a gala ‘Musical Exposition’ of opera and ballet in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the declaration of the Kingdom of Italy. Among the notable events were the company premières of Verdi’s Macbeth and Donizetti’s Don Sebastiano and the Italian première of La Fanciulla del West, with Eugenia Burzio and Giovanni Martinelli. Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe presented local premières of Les Sylphides and Giselle with Nijinsky, and Toscanini conducted several of the operas. In the midst of this carnival of riches, on 16 April, 1911, De Angelis débuted as Don Basilio with the stellar cast of Graziella Pareto, Umberto Macnez, Titta Ruffo and Giuseppe Kaschmann. The theatre was packed with family, friends, colleagues from his days at the Vatican and the Conservatorio, and former teachers. Dal Costanzi all’Opera states that “it was an evening of surpassing grandeur, refinement and polish, a performance beyond any criticism”. Il Giornale d’Italia reported that “De Angelis convinced a highly expectant audience that he is truly an artist of the first rank….The tumultuous applause that greeted the singers became a roar each time that he appeared before the great curtain”. He was to tell Paolo Silveri many years later that it was the most emotionally satisfying evening of his career. The bond between singer and city had been permanently cemented and he would return in thirteen additional seasons in seventeen roles.

On 23 May, De Angelis debuted at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires as the Landgrave in Tannhauser with Pasini-Vitale, Ferrari-Fontana and De Luca. He sang in ten operas, including his first performances in Don Carlo with Agostinelli, Garibaldi, Constantino and Ruffo, La Sonnambula with Barrientos and Bonci and I Puritani with Barrientos, Bonci and De Luca. The Colon hosted him the following year in seven operas, including his only performances as Friar Lawrence in Gounod’s Romeo et Juliette with Lucrezia Bori and Giuseppi Anselmi. De Angelis sang at the Colon for the last time in 1914, but he returned to Buenos Aires in 1919 as Basilio, Mefistofele, Galitzky, Mose and Archibaldo at the Teatro Coliseo.

On 10 October, De Angelis sang Mefistofele at the Costanzi for the first time, and it would be the defining event of his career. The first night audience cheered for nearly an hour and the next day’s reviews were among the most laudatory ever seen:

Mefistofele at Rome - Il Corriere d’Italia - 11 October, 1911. “This singer and magnificent actor can truly claim to be the greatest basso currently on the lyric stage. Extraordinary power, an excellent voice, clear and perfect diction and impeccable technique were all completely confirmed last night. His success was enormous.”

His triumph was reported on the front page of newspapers throughout Italy and he was immediately asked to sing the role in virtually every Italian theatre. Within four months he had débuted at Turin’s Regio, Trieste’s Verdi and the San Carlo of Naples, where he sang fourteen performances of the opera. Barcelona’s Liceo received him with enormous acclaim in April of 1913 and Mefistofele was to serve as his debut role at Venice’s Fenice, Genoa’s Carlo Felice and Politeama, Brescia’s Grande, Padua’s Verdi, Palermo’s Massimo and the Verona Arena. In 1918, De Angeles sang the role for the first time at La Scala with Linda Cannetti, Elena Rakowska and Gigli, and, in 1920, at Milan’s Dal Verme, he appeared in some fifteen performances of the opera with Hina Spani as Margherita. It was so overwhelming a part of his career, that in 1923, it was the only role he sang.

On 4 April, 1915, he sang Mosè for the first time, appearing at Rome’s Teatro Quirino and took the role to Firenze, Livorno’s Teatro Goldoni, the Comunale of Bologna and Milan’s Dal Verme. The cast included Giannina Russ, Adele Ponzano, Luigi Pieroni and Alessandro Dolci, and was conducted by Mascagni. The tour was among the very few performances he gave between the Spring of 1915 and the Winter of 1918. A 1916 press release from the Teatro Municipal of Santiago, Chile notes that, because he was serving in the Italian armed forces, he would not be able to appear. He returned to the stage at Rome’s Costanzi in February, 1918, and sang Mosè there on 23 April.

Mosè - 2 June, 1918 - Rome Dal Costanzi all’Opera. “On the closing night, which presented the tenth performance of Mosè, De Angelis achieved one of the greatest successes of his career.”

La Tribuna said: “The great bass received an ovation perhaps without parallel in memory. His performance was of monumental proportions, and the audience responded in kind.”

Over the next several years, De Angelis sang Mose at La Scala, Buenos Aires, Rosario, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paolo, Bergamo, Genoa, Ferrara, Trieste, Turin, Ancona, and, for the last time in 1925 at the Verona Arena.

Although De Angelis’ stage debut was in Linda di Chamounix, Donizetti and Bellini seem not to have been composers for whom he felt much affinity. In 1911, he sang in La Sonnambula and I Puritani at the Colón of Buenos Aires and, on the closing night of the 1926 season at Rio de Janeiro, he sang one additional lonely performance of I Puritani. By 1912, he had stopped singing in La Favorita and Lucia di Lammermoor and seems never to have appeared in a Donizetti opera again. He sang important revivals of Norma with Giannina Russ, Claudia Muzio, Vera Amerighi-Rutili, Bianca Scacciati and Iva Pacetti, but they were few in number and widely separated in time.

Lucia di Lammermoor at Buenos Aires - La Prensa - 27 May, 1911 Though the soprano role is the centrepiece of this opera, Barrientos’s grand companions, Constantino, Ruffo and De Angelis were all triumphant.

Norma at Rome - Il Tevere - 28 December, 1928 The evening confirmed the triumph of Norma, and of Muzio, Luisa Bertana, the tenor Mirassou and Nazzareno De Angelis, who conferred, with beauty of voice and physical presence, the ultimate realization of Oroveso.

Don Basilio in Il Barbiere di Siviglia was a very important role in De Angelis’s career, and he sang it in both the largest and smallest theatres. In the Spring of 1916 he toured among Parma’s Regio, Naples’ San Carlo, Pisa’s Verdi, Pesaro’s Salon Pedrotti and Rome’s Quirino in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the opera’s premiere. The cast for the performances was Fanny Anitua as Rosina; Carpi and Macnez sang Almaviva; Galeffi portrayed Figaro and Kaschmann, Bartolo. At Rome, the cast included de Hidalgo, Salvati and De Luca. He sang it at the Costanzi in 1919 and garnered his usual superlatives.

Il Barbiere di Siviglia at Rome - Il Messagero - 16 February, 1919 “This old opera rarely has one divo, fewer times two, but tonight there were four, de Hidalgo, Schipa, Galeffi and De Angelis, truly an Olympus of singers. It was a marvellous evening, one which made us almost believe that we were seeing the opera for the first time. The soloists sang as though inspired by some magic spirit.”

In 1919, De Angelis toured to Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paolo as Basilio with Angeles Ottein, Tito Schipa and Armand Crabbe. It was on this tour that he appeared in Prince Igor, Il Guarany and Salvator Rosa for the only times in his career. In 1921 he appeared as Basilio at Spoleto with the inimitable Conchita Supervia and in 1922 he appeared in a lavish production at La Scala with de Hidalgo, Hackett and Galeffi. In 1925 he made both his Swiss debut and farewell as Basilio at Lugano.

His Wagner roles were seven: King Marke in Tristan und Isolde, Wotan in both Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, King Henry in Lohengrin, Hagen in Götterdämmerung, the Landgrave in Tannhäuser and Gurnemanz in Parsifal. In 1914, he sang Gurnemanz an amazing twenty seven times during La Scala’s first season of Parsifal and premièred the opera at Buenos Aires’s Teatro Colón the following May. In January 1922, he returned to La Scala for eleven performances in a cast that included Helene Wildbrunn, Amadeo Bassi, and on the fourth night, the debut at that theater of Apollo Granforte. He appeared at Paris as Gurnemanz in May of the same year. De Angelis appeared in Die Walkuere at Rome, La Scala, Naples, Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paolo and in Das Rheingold at Bologna, Rome and La Scala. In the winter of 1938 at Rome, he sang Wotan in Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, as well as Hagen, in the first ‘Ring’ ever performed completely in Italian. The undertaking was supervised by Tullio Serafin and the four operas were broadcast throughout Italy. De Angelis’ last Wagner performances were as Gurnemanz at the San Carlo of Naples in April, 1938.

Of his performances in the 1938 ‘Ring’at Rome, the following reviews are quoted.

Il Messagero, 25 January - Das Rheingold De Angelis sang with enormous resonance. His achievement was hard to imagine, sung with the greatest of expression, vigour and vibrancy.

Il Piccolo, 27 January - Die Walkuere He maintained a level of excellence throughout this very long and difficult role that was exceptional.

Among Verdi’s operas, he sang Zaccaria in Nabucco, Silva in Ernani. Ferrando in Il Trovatore, Grenvil in La Traviata, Sparafucile in Rigoletto, Tom in Un Ballo in Maschera, Padre Guardiano in La Forza del Destino, Procida in I Vespri Siciliani, Fiesco in Simon Boccanegra, King Philip in Don Carlo, Ramfis in Aida and Lodovico in Otello. Interestingly, he sang far fewer performances of Verdi than he did of Wagner. In fact, in no Verdi opera, outside of Aida, did he sing more than twenty five performances, and Simon Boccanegra, had only one revival, at La Scala in 1933. It was his last new role.

Aida - Rome - La Tribuna - 6 October, 1911 The Ramfis of Nazzareno De Angelis showed an extraordinarily robust, mellow and vibrant voice.

Nabucco - Rome - La Tribuna - 2 June, 1916 A memorable evening of art, of patriotic love.... in which all the artists offered a spectacle of singular interest. The interpreters, Nazzareno De Angelis in the white robes of the high priest, Zaccaria, Carlo Galeffi, Cecilia Gagliardi and Fanny Anitua gave superb examples of their great art.

Non-operatic appearances were fairly infrequent. He sang in Verdi’s Manzoni Requiem several times, most importantly at La Scala in 1913 under Toscanini’s direction, at Rome’s Teatro Augusteo in both 1913 and 1922, and in 1924 at Vicenza and the Verona Arena. The Verona engagement with Rinolfi, Minghini Cattaneo and Taccani, was so successful that after two performances in the outdoor stadium, an additional two were given at the Teatro Filarmonico with Lucia Crestani singing the soprano music. In May 1938 he returned to the work for the last time when he sang it at Rome’s Teatro Adriano with Caniglia, Stignani and Alessandro Granda. On 4 December 1924, under Toscanini’s direction, he and Hina Spani sang at Giacomo Puccini’s Funeral in the Duomo of Milan, and on the 29th , the program was repeated at La Scala. Among De Angelis’ more interesting concerts were three at Rome’s Teatro Quirino. On 4 April 1915 he appeared with Russ and Battistini in an all Mascagni programme honouring the composer. In September, 1915 he appeared in a composition called Inno alla Patria by Zandonai accompanied by Gabriella Besanzoni, and in June 1916, he sang in Canto di Guerra, written by the great bass-baritone Giuseppe Kaschmann.

De Angelis’ career in Iberia was not impressive. He sang Mefistofele at La Coruña, Spain in 1908 and appeared at Barcelona’s Liceo in the Spring of 1913 as Boito’s Devil. The La Coruña engagement includes a reference to Gounod’s Faust, which, if it were to have happened, would have been an extremely interesting juxtaposition of roles. Perhaps it did. There are announcements of a second engagement at La Coruña in 1912, but I have found no details. It would seem, from the evidence, that he never appeared in Portugal.

By 1927, De Angelis was averaging no more than 20 performances a year, though he continued to make recordings at a prodigious rate. In 1934, his only appearances were as Mefistofele at Piacenza and, about a year later, he sang Oroveso, Gurnemanz and Padre Guardiano at Genoa’s Carlo Felice. After a three-year absence, he returned to Rome’s Teatro Reale in January of 1938 for Mefistofele and the celebrated ‘Ring Cycle’. In August, after a debut at Rome’s Caracalla as Mefistofele, he sang his valediction at Naples’ Arena Flegrea as Boito’s Beelzebub, with Delia Sanzio, Margherita Grandi and Granda. De Angelis had appeared in fifty seven operas and had sung well over fifteen hundred performances.

It has been reported that he gave occasional recitals until about 1942. Upon his eventual retirement, he taught in Milan and, later, at his favorite city, Rome. He died on 14 December, 1962, in Rome, at the age of 81.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Nazzareno de Angelis#bass#Lohengrin#Richard Wagner#Wagner#Paris Opéra#La Scala#classical musician#classical musicians#classical voice#classical history#classical art#musician#musicians#music education#music theory#history of music#historian of music#diva#prima donna

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

loki and sylvie are literally hamlet and ofelia

6 notes

·

View notes