#Eric Toensmeier

Text

Currently Reading

Dave Jacke with Eric Toensmeier

EDIBLE FOREST GARDENS

VOL 2 - DESIGN & PRACTICE

Ecological Vision and Theory for Temperate Climate Permaculture

#Dave Jacke#Eric Toensmeier#farm life#farming#food forest#forest garden#permaculture#reading#sustainability

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

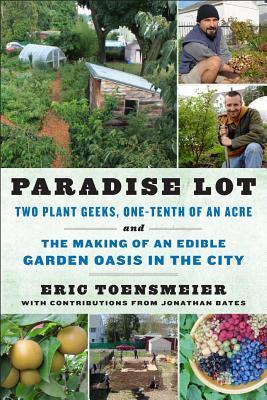

Read Paradise Lot: Two Plant Geeks, One-Tenth of an Acre, and the Making of an Edible Garden Oasis in the City PDF BY Eric Toensmeier

Download Or Read PDF Paradise Lot: Two Plant Geeks, One-Tenth of an Acre, and the Making of an Edible Garden Oasis in the City - Eric Toensmeier Free Full Pages Online With Audiobook.

[*] Download PDF Here => Paradise Lot: Two Plant Geeks, One-Tenth of an Acre, and the Making of an Edible Garden Oasis in the City

[*] Read PDF Here => Paradise Lot: Two Plant Geeks, One-Tenth of an Acre, and the Making of an Edible Garden Oasis in the City

0 notes

Text

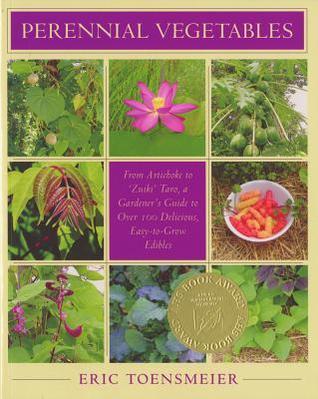

Read PDF Perennial Vegetables: From Artichokes to Zuiki Taro, a Gardener's Guide to Over 100 Delicious and Easy to Grow Edibles EBOOK -- Eric Toensmeier

Download Or Read PDF Perennial Vegetables: From Artichokes to Zuiki Taro, a Gardener's Guide to Over 100 Delicious and Easy to Grow Edibles - Eric Toensmeier Free Full Pages Online With Audiobook.

[*] Download PDF Here => Perennial Vegetables: From Artichokes to Zuiki Taro, a Gardener's Guide to Over 100 Delicious and Easy to Grow Edibles

[*] Read PDF Here => Perennial Vegetables: From Artichokes to Zuiki Taro, a Gardener's Guide to Over 100 Delicious and Easy to Grow Edibles

0 notes

Text

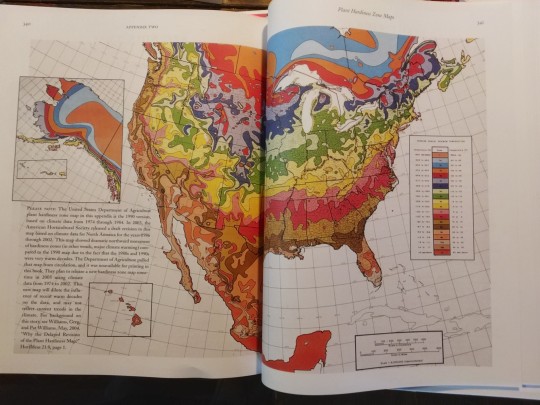

Permaculture for the eastern US

Pretty cool books.

The USDA hardiness zone map is most interesting.

This is the 1990 version. The authors note that this is based on data from 1974-1984. Ten years.

They also note that the American Horticultural Society drafted an updated map in 2003, based on data from 1986-2002. This map showed that the warmer zones were creeping north. 16 years of data.

The Department of Agriculture pulled this new map from circulation, so it wasn't available for this book.

Instead they were going to release a new map, including data from 1974-2002, (28 years), thus diluting the more recent numbers.

The printed 1990 map shows Slaughterhouse House in zone 6b. The most recent 2012 map shows us in zone 7a, and covers the years of 1974-2005. 30 years. That's a half-zone increase, which is 5F/2.8C

There is a nice explainer of the changes in the maps at

https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/apme/51/2/2010jamc2536.1.xml

It has a weak argument for going from the most recent 10 years in 1990 to the most recent 30 years in this round ("more stable statistically", "yields a clearer picture"), so you might want to adjust your hardiness zone accordingly. I'm thinking we may be in zone 7b.

Near us, in Rabun County, GA, there is a resort town called Sky Valley. When D was in high school, it was a ski resort, and she spent a lot of time there, her parents even bought a time share.

I went to the time share once, during the beginning of Operation Desert Storm, January 17, 1991 - we watched it on TV. There was snow on the ground outside, and the 1990 USDA hardiness map was being developed.

I don't remember it being a ski resort then. Things were already changing.

Sky Valley is no longer a ski resort with charming chalets, it's now a golf resort with charming chalets. The ski slopes are gone.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forest Gardens: Create a Food Forest in Your Backyard

If you live somewhere with space for growing food, a forest garden or food forest is one of the best ways to grow it.

What is a Forest Garden?

A forest garden is a garden designed to mimic the interrelationships that exist in the natural environment. As your forest garden gets established it becomes more and more hands-off except for harvesting, creating less work for you and letting nature take the reins.

When you intentionally group and place plants like wild trees, shrubs, ground-cover, and vines together they'll grow symbiotically, requiring no additional fertilizer, water, pest/disease control. This grouping of mutually beneficial plants is called a guild. When you put lots of guilds together you get a forest garden.

A well-known example of a guild is the three sisters, an Indigenous method of growing corn, beans, and squash together in the same mound. The corn grows tall, providing shade for the squash and a trellis for the beans to climb. The beans fix nitrogen in the soil to fertilize the corn and squash. The squash covers the ground, creating a living mulch for the corn and beans. The plants fulfill each other's needs and grow better together than they would separately.

There are infinite ways to create guilds and in turn forest gardens! Fruit tree guilds like these are a great example.

Designing a Forest Garden

You don't need a space the size of an actual forest to grow a forest garden. Even a small bit of land can hold food producing plants. The key is finding a group of plants that all benefit each other so you can create guilds even in small spaces.

Here's a basic guideline to creating a guild:

For every large/tall food producing plant/shrub/tree, include a nitrogen fixing plant/shrub/tree, a plant that attracts beneficial insects, a plant with a deep tap root to pull up nutrients from the soil, and a ground cover to create a living mulch.

This is a step up from the three sisters, and it can go even further! Forest gardens can be as huge or as small as you want them to be.

Consider the sun. All of your plants will need adequate sunlight, so plant your tallest plants to the north, then moving south plant your smaller trees, vines, herbs, and ground covers.

Figuring out What to Grow in Your Food Forest

So many plants can thrive in a food forest. What you grow is going to need to be tailored to your space, your needs, and your climate.

Both annuals and perennials work well, but perennials are often preferred.

Grow plants native to your area. Learn your growing zone and research your native plants. If you live in the United States this tool from the National Wildlife Federation will show you your native plants by typing in your zip code.

If possible, connect with other permaculturists in your area or growing zone (either on social media or in person!) and learn what they're growing and how they have it organized.

Keep on reading and learning! Books, classes, websites, blogs, YouTube videos, there's so many great resources out there. Gaia's Garden by Toby Hemingway and Edible Forest Gardens by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier are considered some of the best books on the subject. I've found lots of helpful books on free websites like Z Library and the Internet Archives!

Creating a food forest takes a lot of planning, but the end result is so worth it. Better for the land, easier on us, and we still get incredible harvests. Happy growing!🌱

Source

#permaculture#food forest#forest garden#foodforest#forestgardening#backyard food forest#gardening#organic gardening#solarpunk#sustainable farming

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

@whimsandsighs thank you so much, this looks really good and also your reply made me realize I've never posted a list of my favorite related books!!!!! what an oversight! here we go, everyone reply with yours

- "Edible Forest Gardens" by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier, volumes 1&2 - my (signed!) copies of these are some of my most prized possessions. full of invaluable information on how to design and implement successful permaculture plantings tailored to whatever land you're working with, including tables of plants

- "A World of Difference: Encountering and Contesting Development" by Eric Sheppard et al. - technically this is a political economy/geography textbook and it's pretty dense but it is excellent and comprehensive and provided my entire understanding of agricultural colonialism among many other things

- "Food Fight" by Daniel Imhoff - a bit outdated now but goes into a lot of detail about U.S. agricultural policy, specifically the 2014 farm bill, in a quick easy read with a lot of nice infographics

- "Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies" by Seth Holmes - a very good and brutal ethnography of a community of migrant farmworkers, essential reading for U.S. consumers imo

- "Radical Agriculture", ed. Richard Merrill - the essay collection for which this blog is named. ITS GOOD

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

A BRIEF HISTORY OF PERENNIALS CROPS

According to Perennial Vegetables by Eric Toensmeier, most North American gardening and farming traditions come from Europe, where there are very few perennial crops except fruits and nuts.

Cold and temperate Eurasian agriculture centered around livestock, annual grains, and legumes, and early European settlers to North America simply brought their seeds and their cultivation methods with them, including draft animals for plowing up the soil every year.

However, in more temperate and tropical areas of the world, including much of North America, perennial root, starch and fruit crops were actively bred, selected and cultivated. These perennial crops were favored perhaps because they require less work to grow, and lacking large domesticated draft animals, only hand tools were available for farming.

Whatever the origin of our neglect of these amazing plants, we shouldn't ignore these useful and productive foods any longer. Perennial vegetables should be much more widely available, especially because, compared to annual crops, they tend to be more nutritious, easier to grow, more ecologically beneficial, and less dependent on water and other inputs.

BENEFITS OF PERENNIAL CROPS:

PERENNIAL CROPS ARE LOW MAINTENANCE

Imagine growing vegetables that require just about the same amount of care as perennial flowers and shrubs—no annual tilling and planting. They thrive and produce abundant and nutritious crops throughout the season. Once established in the proper site and climate, perennial vegetables planted can be virtually indestructible despite neglect. Established perennials are often more resistant to pests, diseases, drought, and weeds, too.

In fact, some perennials are so good at taking care of themselves that they require frequent harvesting to prevent them from becoming weeds themselves! The ease of cultivation and high yield is arguably the best reason for growing them.

PERENNIAL CROPS EXTEND THE HARVEST

Perennial vegetables often have different seasons of availability from annuals, which provides more food throughout the year. While you are transplanting tiny annual seedlings into your vegetable garden or waiting out the mid-summer heat, many perennials are already growing strong or ready to harvest.

PERENNIAL CROPS CAN PERFORM MULTIPLE FUNCTIONS

Many perennial vegetables are also beautiful, ornamental plants that can enhance your landscape. Others can function as hedges, ground covers or erosion control for slopes. Other perennial veggies provide fertilizer to themselves and their neighboring plants by fixing nitrogen in the soil. Some can provide habitat for beneficial insects and pollinators, while others can climb trellises and provide shade for other crops.

PERENNIAL CROPS HELP BUILD SOIL

Perennial crops are simply amazing for the soil. Because they don’t need to be tilled, perennials help foster a healthy and intact soil food web, including providing habitat for a huge number of animals, fungi and other important soil life.

When well mulched, perennials improve the soil’s structure, organic matter, porosity and water-holding capacity.

Perennial vegetable gardens build soil the way nature intended by allowing the plants to naturally add more and more organic matter to the soil through the slow and steady decomposition of their leaves and roots. As they mature, they also help build topsoil and sequester atmospheric carbon.

DRAWBACKS OF PERENNIAL CROPS

Some perennial vegetables are slow to establish and may take several years to grow before they begin to yield well. (Asparagus is a good example of this.)

Like many annuals, some perennial greens become bitter once they flower, therefore they are only available very early in the season.

Some perennials have strong flavors which many Americans are unaccustomed to.

Some perennials are so low-maintenance that they can quickly become weeds and overtake your garden, or escape and naturalize in your neighborhood. (Daylilies are a good example of this.)

Perennials vegetables need to be carefully placed into a permanent place in your garden and will have to be maintained separately from your annual crops.

Perennials have special pest and disease challenges because you can’t use crop rotation to minimize problems. Once some perennials catch a disease, they often have it forever and need to be replaced.

PERENNIAL CROPS GROWN AS ANNUALS

Some perennial crops are grown as annuals because they are easier to care for that way. For example, potatoes are technically perennials, but we grow them as annuals because pests and disease pressure in North America requires us to rotate potatoes often.

On the other hand, some plants we grow as annuals do quite well as perennials, like kale.

CULTIVATING PERENNIAL CROPS

One way to incorporate perennial veggies into your garden is to expand the edges of an already established garden. Simple extend an existing garden bed by 3 or 4 feet and plant a border of perennials there.

Or, if you already grow a perennial ornamental border or foundation shrubs, consider integrating some perennial vegetables, such as sea kale or sorrel. Many have attractive leaves or flowers to enhance the landscape.

You can also take advantage of currently unused areas of your landscape, matching the conditions to the appropriate perennial. There are some perennials, like wild leeks, that will grow in shady, wet or cool conditions where you couldn't ordinarily grow food!

If you’re already growing perennial vegetables and want to take your garden or homestead to the next level, consider Permaculture gardening.

By imitating nature’s ecosystems, this approach promotes greater partnerships between plants, soil, insects, and wildlife. In Permaculture designs, edible vegetables, herbs, fruiting shrubs and vines grow as an understory to taller fruit and nut trees. This technique is sometimes called “layering” or building a “guild.”

Layers or Guilds need to be built over a couple of years. In the first year, plant fruit trees as the outposts around your property. That same year and over the next several years, use sheet mulching to prepare planting areas beneath the trees for the understory plants. Sheet mulch a 2- to 3-foot-radius around each fruit tree the first year and gradually increase the mulched area as the trees grow.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Readers Respond to the August 2020 Issue

Readers Respond to the August 2020 Issue

[ad_1]

In “The Biomass Bottleneck,” Eric Toensmeier and Dennis Garrity address the strategy of drawing down billions of tons of carbon dioxide by using biomass for energy and carbon capture. Their analysis concludes that the amount of biomass required would leave the world with inadequate arable land to grow food. And they indicate that available biomass waste that currently has no other use is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Waiting for Skirret seed to ripen. This Umbelliferous plant has slender, sweet, white roots that grow in clumps. It is from northeastern Asia (where it is still eaten), and was very popular in medieval Europe, but like the Parsnip, it was cast aside when the Andean Potato arrived on the scene. According to Eric Toensmeier in “Perennial Vegetables”, this perennial tastes best when you eat some of the older roots when dividing the plants - not when grown from seed (as I’ve done). #skirret #siumsisarum #seedkeeping #seedsaving #perrenialvegetables (at Delaware County, Pennsylvania)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Reading

Dave Jacke with Eric Toensmeier

EDIBLE FOREST GARDENS

VOL 1 - VISION & THEORY

Ecological Vision and Theory for Temperate Climate Permaculture

#Dave Jacke#Eric Toensmeier#farm life#farming#food forest#forest garden#permaculture#reading#sustainability#biodynamic farming

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Perennial Vegetables by Eric Toensmeier – Item of the Day https://ift.tt/2hsnIFw

0 notes

Link

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J via The Survival Podcast

0 notes

Text

weeds - friends to the soil

When thinking about how best to prepare any type of disaster, natural or otherwise, one of the first questions that always comes up (apparently after how much toilet paper do I need to stockpile), is where do we get our food? Say you’ve got a supply of some cans and non-perishables stored away… is there a way to ensure you will still have some noms if you aren’t at home, or your house is impacted, or you run out of edible supplies when disaster strikes?

Since I was young I have been in love with the idea of foraging and understanding ecosystems enough to know what different plants are telling us. I recently read The Hidden Life of Trees written by Peter Wohlleben, a German forester who started studying the trees in the forests he helped commodify. He figured out so many insights about how a forest is doing, what the natural age of trees and their progressions through life look like in various conditions, which ones play well with others and which ones bide their time until they can takeover. He addresses forest fires and moisture-loss, how and why trees grow weak and unstable when their root system is maimed (which is why you see so many felled trees have those huge horizontally spreading root systems!), and more. (Did you know most of the time moss is not a good indication of which way civilization is? It forms on the side of the tree where rainwater drips down, so only if civilization causes specific tree warping patterns would it really line up.) Anyway, it was a fascinating book that argued maybe we need to look at trees a bit more like how we see animals rather than just as firewood and lumber, and it gave logical reasons for why we shouldn’t clear old trees from forests. In general the book helped me start to think about different frameworks for how we can think about ecosystems, from forests to our local suburban landscapes.

It was after that book that I started back in on permaculture books, finishing up Paradise Lot by Eric Toensmeier and Jonathan Bates the other night. Though I have differing ideas on a few points, I’m pretty confident that I have found my people. I have been getting all manner of ideas and new knowledge that I am eager to try out in our backyard (and to some extent the front, depending on how much we can do without the HOA getting annoyed) from this book. With all these new plans swirling in my head, I started looking into how to be more self-reliant especially in a suburb. Most of the country lives in suburbs of some sort now and we tend to waste our resource spaces with grass and large houses, furthering dig ourselves into the mud should grocery stores shut down/online shopping go offline. And so began my quest on how to start to amend that trend, beginning with our own little family. In a future post I’ll talk about water conservation after I’ve learned more.

Since the weather has been warming, Figlet and I have been adventuring outside in our backyard often to figure out what’s already happening out there, sans human intervention. We have identified that we currently have a lot of ground ivy, hoary bittercress, wild onion or wild garlic (not sure which yet), and some specific scatterings of daffodils (Narcissus pseudonarcissus), mock/Indian strawberry, and wine raspberry, so I decided to start my permaculture/foraging research with those guys.

What I learned is that all but daffodils are edible, and also that the appearance of many of these plants in a yard can indicate signs about the state of the soil. I’ll go into each below.

Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea)

These pretty little guys are popping up all around our yard mostly around the center bits of our yard, and around the above-ground tree roots. Apparently these guys show up and prevent soil erosion (which supports one of our theories that the hilly nature of our yard means that soil has been getting washed down the hill, exposing the tree roots, what with their horizontal growth, over time). Ground ivy is a cool plant because it was also historically used to brew beer, predating hops! Their presence might indicate that there is a high level of organic matter in the soil, which bodes well since I was hoping to make a sort of mandala of vegetables grow around their areas, in between the tree roots.

Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium purpureum)

I never knew this plant existed (or never noticed it before) but this year I am seeing it everywhere (especially in this one parking lot under the evergreen bushes). I hear the leaves and flowers made into a tea (though too much can cause a laxative effect) and it can be a used as a poultice. They pop up in early spring and are great for pollinators.

Hairy/hoary Bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta)

This guy has edible leaves and flowers, that I’ve read one can use similarly to other cresses (like watercress!). I’m still working on learning more about this little guy.

Wild Garlic (Allium vineale) or wild onion (Allium canadense)

I’m not sure if we have crow garlic (Allium vineale) or wild onion (Allium canadense) but we’ll see when the flowers come up and/or when I get around to digging up some of the bulbs… (or if I just get better at identification). Either way they are the most prolific thing in our yard at the moment, and both are edible. There are also other edible types called Allium ursinum and Allium tricoccum… and basically the internet calls them all wild onion and wild garlic so this is where the scientific names (and photos) really help.

Wine Raspberry (Rubus Phoenicolasius)

This guy is a non-native from Japan. It produces berries similar to raspberries, but apparently are so good, you’ll have to be on the ball to beat the birds to them. They also have intimidating looking spikes and are showing up all in our woods. Peter Wohlleben would probably point out how they are able to take over so easily because the woods don’t have their natural level of fall trees and other debris to kill off such invaders.

Mock/Indian Strawberry (Duchesnea/Potentilla Indica)

I kept thinking these plants were wild strawberry… but the leaves were so weird, and the flowers were yellow. Google led me to Mock Strawberry. Apparently these berries are kind of bland, but the leaves can made into a potherb or they can be made into a poultice and used for eczema!!! HWAHHHH? HELLO FREE HOME REMEDY.

Common Blue Violet (Viola sororia)

These guys are lovely. I don’t know why they are called blue since all our shades are a lovely violet, but oh well. I hear they are great for teas with their lovely flowers.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

The infamous invasive weed that everyone is always trying to pull out. It apparently can be harvested, using the roots like horseradish, sautéing the leaves, and tossing the flowers into salad.

Stonecrop (Sedum sarmentosum)

This succulent looking plant is popping up all around the sunny side of our yard intermixed with the violets and the moss. I read that Koreans will

Moss

Apparently this is a huge sign that our yard has areas that are acidic and soggy (the latter which isn’t surprising since a lot of our yard is in the shade and was buried under full leaves for years).

Other familiar faces of the suburbs

Crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis)

This guy shows up in soil that is lacking nitrogen and calcium. It can also indicate that the soil is acidic, which might be good for some crops like blueberries, potatoes, and tomatoes, but won’t work if it too acidic. I’ll keep searching the yard to see if we have any and add a photo later if I should discover one.

Plantain (Plantago major)

Grows in compacted (heavy trampled) soil, that is often very claylike. Plantains are edible in their entirety (squeezing the juice out of them, or using the leaves) and have a rich history of being used for bladder and GI problems, skin problems, toothaches, you name it! Still looking for some in our yard, but so far I haven’t found any.

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

The infamous yard weed of every traditional grass-growers nightmare. These guys show up in compacted soil, and their presence is actually a good thing because they grow long taproots that help pull nutrients from deep in the soil and help fertilize your yard. Also they are said to grow in places with low calcium but high potassium. Dandelions are also high in a bunch of nutrients and can be used to make tea, used instead of coffee grounds (baking the roots), and their leaves are edible as well for greens. I found this little guy on the side of the house… so many the foundation was made with potassium?? (I know literally nothing about housing materials).

Speedwell (Veronica hederifolia and Veronica filiformis)

I saw the purple version of this (V. hederifolia) flowering next to the sidewalk off the highway by where we live. I then found a different species of it with pink leaves (V. filiformis) in our backyard in one spot, so I might want to get some water-hogging, dirt-aerating plants for there as apparently these guys pop up where the soil has bad drainage and compaction.

My gardening direction

As I learn more, I find myself so excited to experiment with the land we are renting. I’m like a mad scientist, that ignores rhyme and reason and formal frameworks of established scientific directions to be like “BUT HOW CAN I GROW THIS WARM SEASON CROP IN THE TAIL END OF WINTER RIGHT NEXT TO THIS INVASIVE NATIVE WEED?!” I realized my style of gardening is pretty aggressively minimalist (and insane/defying convention and years of human cultivation strategies). I want to learn how to garden without any enhancements… no added soil, no external mulch, no buying lime or sand… basically only growing with the land and current ecosystem I have, general gardening tools (a shovel, an aerating fork thing, a smaller trowel), sticks and logs for fences, recycled things from the house (I used egg cartons to start some seeds indoors on window sills but am now trying to grow without that method as well), kitchen scraps for compost, and then my one caveat is buying seeds. My thought is that it would be interesting to see how someone could take whatever land they have, whatever the conditions, and really work with what they have to see what they could produce. I can take it to the extreme and say I’m curious to see how can we grow and make food when Home Depot, Lowes, Tractor Supply Co, etc are barren and we have to just know how to grow with those packets of seeds we stored long ago and nothing else but the land we are near. I want to learn how to tend to the land that has been completely overhauled by humans… de-forested years ago, landscaped down to the weirdest of conditions, probably with big ole trees erratically sticking roots up aboveground, or patches of dry clay near housing foundations. I want to experiment to see how one can really work with the remaining surviving weedy nature and see if humans can live off, and tend to that kind of land. Stay tuned to more adventures as the seasons progress, if I am successful or fail miserably.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Permaculture[

edit

]

Bill Mollison, who coined the term permaculture, visited Robert Hart at his forest garden in Wenlock Edge in October 1990.[30] Hart's seven-layer system has since been adopted as a common permaculture design element.

Numerous permaculturalists are proponents of forest gardens, or food forests, such as Graham Bell, Patrick Whitefield, Dave Jacke, Eric Toensmeier and Geoff Lawton. Bell started building his forest garden in 1991 and wrote the book The Permaculture Garden in 1995, Whitefield wrote the book How to Make a Forest Garden in 2002, Jacke and Toensmeier co-authored the two volume book set Edible Forest Gardens in 2005, and Lawton presented the film Establishing a Food Forest in 2008.[31][32][33]

Austrian Sepp Holzer practices "Holzer Permaculture" on his Krameterhof farm, at varying altitudes ranging from 1,100 to 1,500 metres above sea level. His designs create micro-climates with rocks, ponds and living wind barriers, enabling the cultivation of a variety of fruit trees, vegetables and flowers in a region that averages 4 °C, and with temperatures as low as -20 °C in the winter.

0 notes

Text

Perennial Vegetables

From Artichokes to Zuiki Taro, A Gardener’s Guide to Over 100 Delicious and Easy to Grow Edibles

By Eric Toensmeier

Chelsea Green

2007

There is a fantastic array of vegetables you can grow in your garden, and not all of them are annuals. In Perennial Vegetables the adventurous gardener will find information, tips, and sound advice on less common edibles that will make any garden a perpetual, low-maintenance source of food.

Imagine growing vegetables that require just about the same amount of care as the flowers in your perennial beds and borders—no annual tilling and potting and planting. They thrive and produce abundant and nutritious crops throughout the season.

It sounds too good to be true, but in Perennial Vegetables author and plant specialist Eric Toensmeier (Edible Forest Gardens) introduces gardeners to a world of little-known and wholly underappreciated plants. Ranging beyond the usual suspects (asparagus, rhubarb, and artichoke) to include such “minor” crops as ground cherry and ramps (both of which have found their way onto exclusive restaurant menus) and the much sought after, anti-oxidant-rich wolfberry (also known as goji berries), Toensmeier explains how to raise, tend, harvest, and cook with plants that yield great crops and satisfaction.

Perennial vegetables are perfect as part of an edible landscape plan or permaculture garden. Profiling more than 100 species, illustrated with dozens of color photographs and illustrations, and filled with valuable growing tips, recipes, and resources, Perennial Vegetables is a groundbreaking and ground-healing book that will open the eyes of gardeners everywhere to the exciting world of edible perennials.

See the book.

from Gardening http://www.cityfarmer.info/2018/04/17/perennial-vegetables/

via http://www.rssmix.com/

0 notes