#Elizabeth of Bohemia

Text

I am sorry for displaying an absolutely juvenile sense of humour, but this poor chap did not exactly win the lottery with this name...

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

As someone whose interest in the Middle Ages is set in the pre-WOTR eras, I occasionally read scholarship on it and sit there blinking because like. wow. wow. this is what being lost in the sauce is like. Historians are really so attached to their ideas of what people are like they've lost all sense of context

Like, I read Michael Hicks going on about how Elizabeth Woodville pursuing Sir Thomas Cook for queen's gold was evidence of harassment and an attempt to punish him twice even though Elizabeth's pursuit of queen's gold was hardly unusual. It also makes me wonder what Hicks would say about Anne of Bohemia pursuing William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury for queen's gold to the point of having the sheriff of Kent distraining him (seizing his goods) until Courtenay complained to the king (and this is apparently despite the parliament declaring the month before Courtenay's complaint that queen's gold did not apply to payments made to enter archbishoprics).

I mean, the issue is reputation - Anne of Bohemia is "good queen Anne", typically depicted as passive and meek, while Elizabeth Woodville's reputation typically runs to the gold-digging, ambitious femme fatale and bad queen.

#wotr historiography is really that bad huh#blog#elizabeth woodville#anne of bohemia#william courtenay archbishop of canterbury#queen's gold#queenship#reputation and representation

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

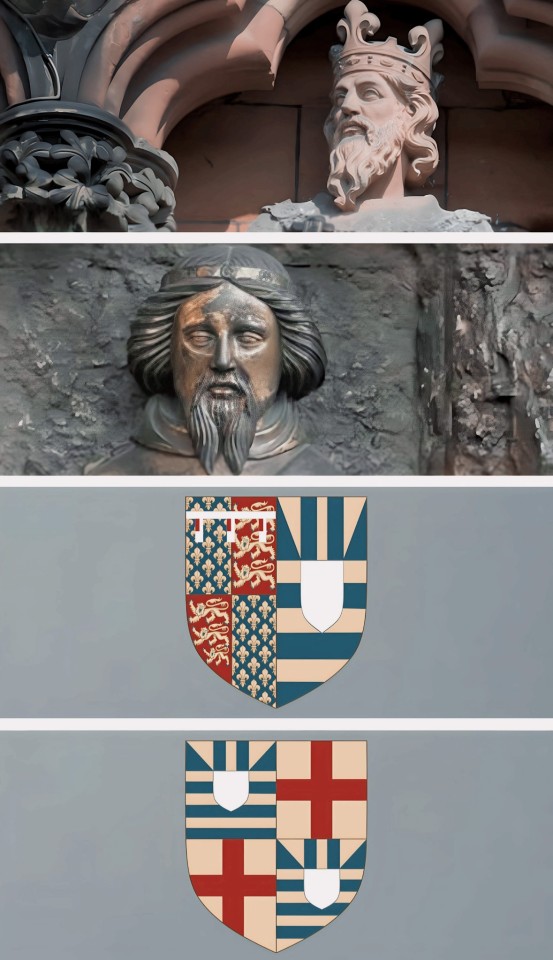

CONSORTS OF ENGLAND SINCE THE NORMAN INVASION (2/5) ♚

Eleanor of Castile (November 1272 - November 1290)

Margaret of France (September 1299 - July 1307)

Isabella of France (May 1308 - January 1327)

Philippa of Hainault (January 1328 - August 1369)

Anne of Bohemia (January 1382 - June 1394)

Isabella of Valois (October 1396 - September 1399)

Joan of Navarre (February 1403 - March 1413)

Catherine of Valois (June 1420 - August 1422)

Margaret of Anjou (May 1445 - May 1471)

Elizabeth Woodville (May 1464 - April 1483)

#my photoset.#history#historyedit#history edit#plantagenets#lancaster#house of lancaster#house of york#elizabeth woodville#margaret of anjou#catherine of valois#the king netflix#the white queen#joan of navarre#isabella of valois#anne of bohemia#philippa of hainault#isabella of france#margaret of france#eleanor of castile#royalty#royals#medieval history#medieval queens#queen consorts#war of roses#english history#historical royals#consorts of england#consorts of england and britiain.

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

why do historical fiction authors have to make their heroines so god-awful?

#constance of york deserves better than those horrible novels#catherine de valois deserves better than literally any novel ever written about her#anne of bohemia deserves better than josephine tey's shitty play#elizabeth woodville deserves better than literally every novel written about her#etc etc etc#text posts#and the thing is that all of these women HAVE really interesting fascinating lives that SHOULD have novels written about them#but the ones that exist are so terrible

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Descendants of the Tudors

#descendants of the tudors#henry vii#margaret tudor#james v#mary queen of scots#james vi and i#elizabeth stuart queen of bohemia#henry frederick hereditary prince of the palatinate

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

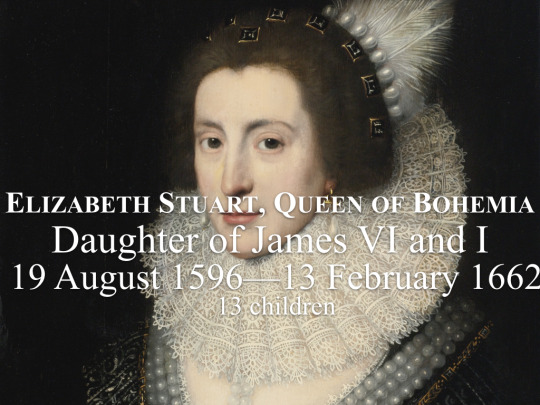

Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia (1642) by Dutch painter Gerard von Honthorst.

Despite not being overly affectionate to her children, Elizabeth was very involved in their education. Her daughters were also taught the classical languages alongside their brothers. According to author Nadine Akkerman, she even taught her children six languages herself! If she was present in these modern times, she would have been a teacher.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

@balldwin said: [ BEHIND ]: upon entering the same room as the receiver, the sender steps behind them, and winds their arms around the receiver’s waist, drawing them close against them.

Perhaps because he is the lord of his own demesne, he doesn’t knock when he enters, or announce himself beforehand—he simply opens the door and steps inside, ignoring the various noises of surprise and, in the case of one of the maids fluttering around her, outright disapproval. For her part, Astoria only spares him a smile and a raised eyebrow over her shoulder.

She knows that look—moreover, she knows not to argue with it. “Excuse us, please,” Astoria instructs, already taking a polite step away and waving a hand vaguely towards the door. When one of the maids, a woman in her forties with a particularly earth-shaking scowl, opens her mouth in protest, he cuts in before she can, voice smooth and sharp at once.

“No need for you to dress her when I’ll be undoing all your work in a moment,” he says with the arrogant nonchalance of the obscenely wealthy and spectacularly powerful; one of the younger maids lets a giggle escape before slapping a hand over her mouth in embarrassment, and eventually all three of them have filed out of the room. Even before they’ve closed the door behind them Baldwin is behind her, hands settling at her sides, nose tucked in her loose hair; they are, as ever, a picture of perfection, wedded bliss to an extreme. It had been at once brilliant and impossibly stupid of her to recommend marriage as a cover a decade before and she is suffering for it now, all too aware of the way his fingers fit against her ribs, their skin separated by only the thin layer of her shift.

He should step back once the door has closed and there’s no audience for whom he could continue the charade. He doesn’t. Astoria is absurdly grateful for it. “You’ll have to lace me into my corset,” she says after a beat. “I can’t do it myself.” But the last thing Baldwin seems interested in is giving her more layers; instead, he lets one of his hands skim across her abdomen, low over her stomach, before settling on the opposite hip, and he tugs her closer to him until her back is flush against his chest. He lifts his other hand, a small, folded square of paper between his fingers. When she takes it and opens it, he lifts his head to read over her shoulder, his newly-freed hand mirroring the first before settling against her side.

“You made an impression on my father,” he observes dryly, and Astoria lets out a spectacularly graceless snort of laughter as she reads.

“A good impression,” she retorts, and Baldwin doesn’t argue. She’ll count that as a victory. “I confess, though—when he said I might be useful I expected something a bit more... clandestine, I suppose, than this.”

Perhaps she’s getting used to him. She’s managed to maintain her composure, which is a victory, even if it’s taking far more energy and attention than she thinks it should to do so. Even with her acute awareness of his hands on her, she’s managed to contain the strangled noise sitting at the back of her throat, the shiver that usually follows such attentive touch. As if reading her thoughts, he taps one of his fingers idly against her hip before sweeping his thumb back and forth over the fabric of her shift, and without fail the strangled noise claws its way out of her. much to his obvious amusement. In retaliation, she presses back against him, but it’s a futile gesture: he simply tightens his arms around her, holding her in place, leaving Astoria to try not to whine.

So. Not used to him at all.

“It’s an interesting choice, throwing another Catholic at the problem.” He says Catholic with the same idle disgust with which she says horse shit, though she’s grown fond of his teasing, even on a matter such as her faith. “Particularly at a wedding.”

But Philippe isn’t simply offering up just another Catholic. He’s offering up a Catholic woman. Whatever else Elizabeth Stuart might be, she is no doubt in need of friends. Where Matthew had apparently failed to win the Prince-Elector’s favor, Astoria—charming and clever and cunning—might gain ground with his young bride. The note in her hands is brief, a short list of names and titles she must commit to memory, and when she’s done that she folds it again, to tuck away in the event that she needs the reminder later.

Westminster is buzzing with activity, Whitehall alive with movement; a royal wedding is cause for celebration, even when the groom, if rumor is to be believed, fails to meet the king’s standards for his daughter. But sweet Elizabeth seems fond of her Frederick, and she has enjoyed Astoria’s company in the past, and if her favor can be kept, it gives them another way in to Bohemia, after some falling out between Philippe and Rudolf some twenty years ago, a falling out Philippe refuses to explain to anyone.

(The only discussion he had allowed on the subject had been an imperious decree that if the Habsburgs cared so little for the support of the de Clermonts, perhaps the de Clermonts were best served by seeking out Habsburg enemies. And here he had looked between Astoria, sitting at Baldwin’s desk, and Baldwin standing behind her, one hand on her shoulder as he watched his father, before offering one of his mercurial smiles. “No need to get attached,” he’d added. “The Emperor will learn his place.” He’d left them both confused, and once he’d left the house to hunt Astoria and Baldwin found themselves sharing one of the more comfortable chairs, Astoria having dropped into his lap under the guise of being able to speak quietly and without being overheard, Baldwin taking the opportunity to quiz her on her Czech by refusing to answer her in any other language until he let out a sigh and a murmur of we’ll work on that before shifting to German.)

“I doubt anyone will be paying much attention to me, Catholic or no,” she answers with a huff of laughter, and the hand at her hip falls a bit lower, grazing the top of her thigh, just in time for the laugh to become a low, keening whine.

“Don’t underestimate people,” he warns, bowing his head so that his lips are at her ear, and when Astoria feels the telltale shiver shooting through her Baldwin’s arms tighten as if he means to pull her under his skin. “What would keep anyone from paying attention to you?”

“The princess, for one.” But Astoria’s retort is strangled, her voice odd even to her own ear. The door behind them opens and she catches the scent of the younger of the maids, hovering anxiously as if waiting for the right moment to interrupt, to insist that the lady must be dressed. Baldwin’s hold on her slackens for only a moment and she takes full advantage, turning in his arms. Her palms rest lightly against his chest, fingers tapping an idle rhythm, and she tips her head to the side and offers him her most indulgent smile. And even with the fierce blush staining her cheeks and the hoarseness of her voice, she knows he’s not immune to her, any more than she is to him. “It’s bad form to let the bride know your eyes are anywhere else.”

One of her hands glides across his chest to curl against the side of his neck, her thumb brushing along his jaw. Baldwin has sixteen centuries on her, enough to have taught him self control, and she revels in the little signs he can’t hide—the darkening of his eyes as one of his hands drags to the small of her back to keep her held as close to him as he can manage; the flex of his fingers against her side, like he wants to press beneath her rib cage and hold her beating heart in his hand; the way that he leans forward until they’re nearly nose to nose, perhaps ignoring their silent audience, more likely enjoying any opportunity to push Astoria. Proof that he thinks of her the way she thinks of him—proof that her desire to be claimed is not without cause. Proof that she hasn’t imagined it all.

(Someday he’s going to push farther still, audience or no, and he’ll take what she holds up to him in offering.)

“Will you keep your focus on the task at hand, if the bride will demand all of your attention?”

“Baldwin.” And she says his name like it’s something holy; she wants to let it sit on her tongue like the body and blood, untouched as it becomes a part of her. “It’s not Elizabeth I fear will hold my attention.”

He grins, then, falls silent for long enough that Astoria forgets entirely that there’s anyone else in the room. When he speaks, she nearly stumbles into him, startled by the reminder that anything else could possibly exist besides him, and his clever hands, and his smile. “I know,” he says, loud enough for the maid to hear. “My wife needs to be dressed. Bring me her corset.” As the maid clears her throat, sounding chagrined at being acknowledged, and shuffles across the room, Baldwin brings his lips to Astoria’s ear again with a quiet turn around.

He laces her tightly enough that, were she human, it might be painful, but as she is, it feels like a challenge.

(Someday he’ll take what she offers and she won’t know what to do with herself besides beg him not to let her go.)

She references the list of names and titles again before she leaves her room, all knowledge of everything but him forgotten in favor of the memory of his hands.

#balldwin#i. here's the truth from my red lips. ( answers )#iii. the rest of you (the best of you) belongs to me. ( baldwin x astoria )#(1613 whitehall in london! king james vi & i's daughter elizabeth marries frederick v who will for a single year be the king of bohemia)#(before the habsburgs take the throne back)#(you CANNOT convince me that it wasn't because philippe was angry that since rudolf (and later matthias) the bohemian court—)#(—hasn't been particularly friendly to the de clermonts. something about matthew and theft. i guess we'll never know.)#(anyway astoria is going to spend the entirety of the wedding pretending she's not thinking abt baldwin putting the altar to better use)#(i imagine he's going to have a blast watching her pretend to be a remotely respectable person)#(i love them thank u)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The 8,000 mourners filed out of Vienna’s St. Stephen’s Cathedral and fell in line behind the catafalque drawn by six black horses. Two hours later the procession ended at the Capuchin Church, where, in keeping with tradition, a member of the funeral party knocked on the door and a priest asked, “Who goes there?”

The titles were read aloud: “Queen of Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, Galicia. Queen of Jerusalem. Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Cracow…”

“I do not know her,” said the father.

A second knock and “Who goes there?” brought the response, “Zita, Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary.” Again the reply, “I do not know her.”

When the inevitable question was put a third time, the answer was simply, “Zita, a sinning mortal.”

“Come in,” said the priest, opening wide the door not for royalty, but for a faithful member of the Church, whose life had finally reached its end.

~ People Magazine

#quenn elizabeth#empress zita#royalty#rip qe2#vienna#st stephen cathedral#st georges chapel#bohemia#dalmatia#england#scotland#wales#galicia#jerusalem#tuscany#slavonia#croatia#cracow#austria#hungary#sinner#come in#people magazine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Practice English

share.libbyapp.com/title/653916

View On WordPress

#Alexander Korda#Anne of Bohemia#bookporn#Dirk Bogarde#Douglas Fairbanks Jr.#DV#Elizabeth MacKintosh#English as a Second Language#ESL#giallo#Gordon Daviot#John Gielgud#Josephine Tey#la source#Libby#Lidia#Lillian Gish#Los Misterios#Martha#metatempesta#New Theatre#Noir#practice English#Richard II of England#Richard of Bordeaux#Scotland Yard#Theater

0 notes

Text

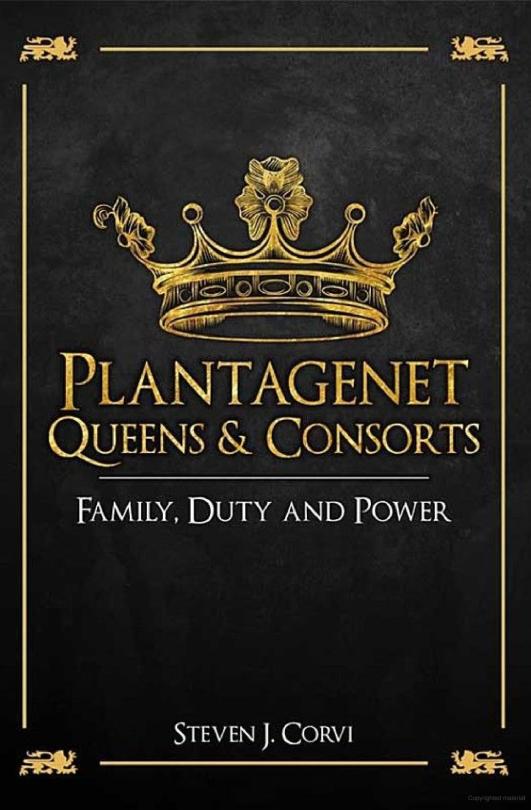

A BOOK ON PLANTAGENET QUEENS-BUT WHERE IS ANNE?

A review of Plantagenet Queens and Consorts by Steven J. Corvi

I am always partial to a good book on medieval English Queens. History being what it is, these women often get overlooked and sidelined unless they did something that was, usually, regarded as greedy, grasping or immoral. Therefore when I saw Steven J. Corvi’s book ‘Plantagenet Queens and Consorts’ I thought that sounded right up…

View On WordPress

#"Beauforts"#"Lambert Simnel"#"Tudor" rebellions#"Tudors"#Anne Neville#Anne of Bohemia#Bermondsey Abbey#Eleanor of Aquitaine#Eleanor of Castile#Eleanor of Provence#Elizabeth of York#Henry III#Henry VII#House of York#Joan of Kent#Joan of Navarre#John of Gaunt#Katherine de Roet#Lady Eleanor Talbot#Marguerite of France#Plantagenet Queens and Consorts#pre-contract#Richard II#Richard III

0 notes

Text

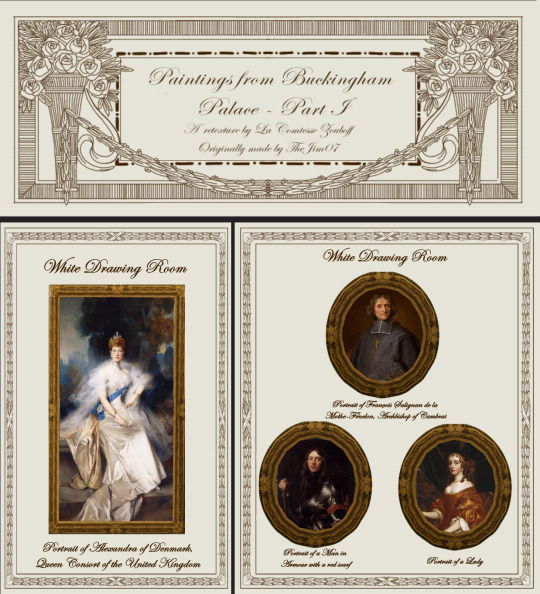

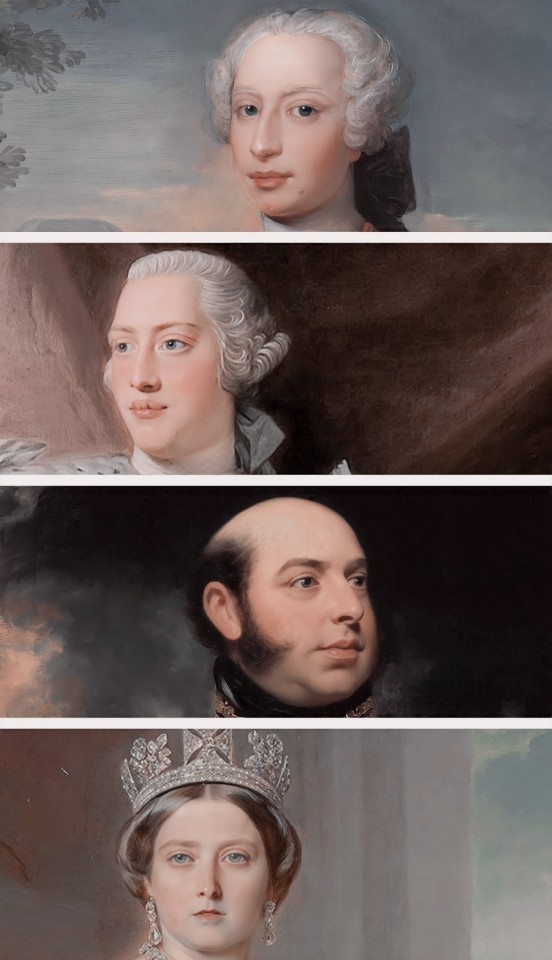

Paintings from Buckingham Palace: part I

A retexture by La Comtesse Zouboff — Original Mesh by @thejim07

100 followers gift!

First of all, I would like to thank you all for this amazing year! It's been a pleasure meeting you all and I'm beyond thankful for your support.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the Royal Collection Trust. The British monarch owns some of the collection in right of the Crown and some as a private individual. It is made up of over one million objects, including 7,000 paintings, over 150,000 works on paper, this including 30,000 watercolours and drawings, and about 450,000 photographs, as well as around 700,000 works of art, including tapestries, furniture, ceramics, textiles, carriages, weapons, armour, jewellery, clocks, musical instruments, tableware, plants, manuscripts, books, and sculptures.

Some of the buildings which house the collection, such as Hampton Court Palace, are open to the public and not lived in by the Royal Family, whilst others, such as Windsor Castle, Kensington Palace and the most remarkable of them, Buckingham Palace are both residences and open to the public.

About 3,000 objects are on loan to museums throughout the world, and many others are lent on a temporary basis to exhibitions.

-------------------------------------------------------

This first part includes the paintings displayed in the White Drawing Room, the Green Drawing Room, the Silk Tapestry Room, the Guard Chamber, the Grand Staircase, the State Dining Room, the Queen's Audience Room and the Blue Drawing Room,

This set contains 37 paintings and tapestries with the original frame swatches, fully recolourable. They are:

White Drawing Room (WDR):

Portrait of François Salignan de la Mothe-Fénelon, Archbishop of Cambrai (Joseph Vivien)

Portrait of a Lady (Sir Peter Lely)

Portrait of a Man in Armour with a red scarf (Anthony van Dyck)

Portrait of Alexandra of Denmark, Queen Consort of the United Kingdom and Empress of India (François Flameng)

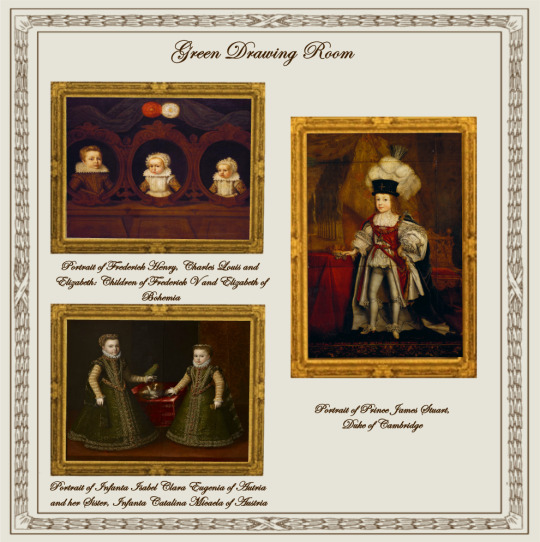

Green Drawing Room (GDR):

Portrait of Prince James Stuart, Duke of Cambridge (John Michael Wright)

Portrait of Frederick Henry, Charles Louis and Elizabeth: Children of Frederick V and Elizabeth of Bohemia (unknown)

Portrait of Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia of Autria and her Sister, Infanta Catalina Micaela of Austria (Alonso Sanchez Coello)

Portrait of Princess Louisa and Princess Caroline of the United Kingdom (Francis Cotes)

Portrait of Queen Charlotte with her Two Eldest Sons, Frederick, Later Duke of York and Prince George of Wales (Allan Ramsay)

Portrait of Richard Colley Wellesley, Marquess of Wellesley (Martin Archer Shee)

Portrait of the Three Youngest Daughters of George III, Princesses Mary, Amelia and Sophia (John Singleton Copley)

Silk Tapestry Room (STR):

Portrait of Caroline of Brunswick, Princess of Wales, Playing the Harp with Princess Charlotte (Sir Thomas Lawrence)

Portrait of Augusta, Duchess of Brunswick With her Son, Charles George Augustus (Angelica Kauffmann)

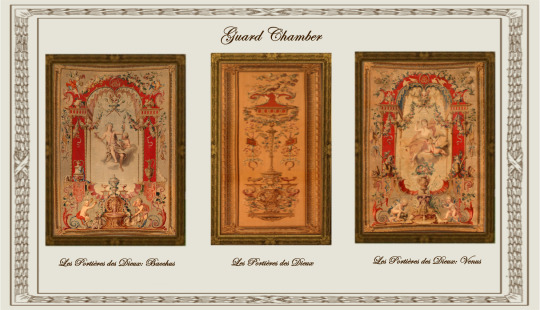

Guard Chamber (GC):

Les Portières des Dieux: Bacchus (Manufacture Royale des Gobelins)

Les Portières des Dieux: Venus (Manufacture Royale des Gobelins)

Les Portières des Dieux (Manufacture Royale des Gobelins)

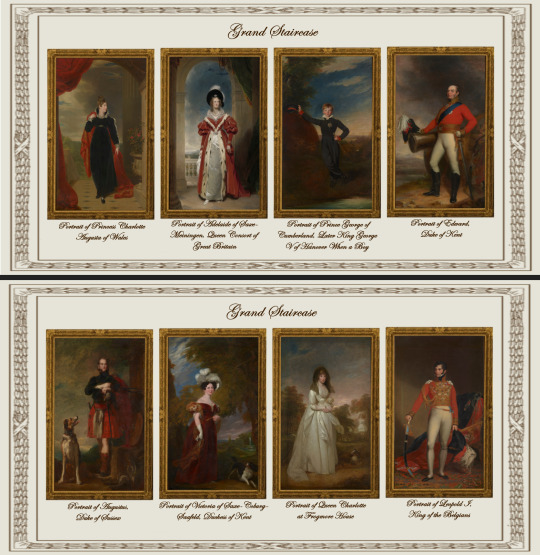

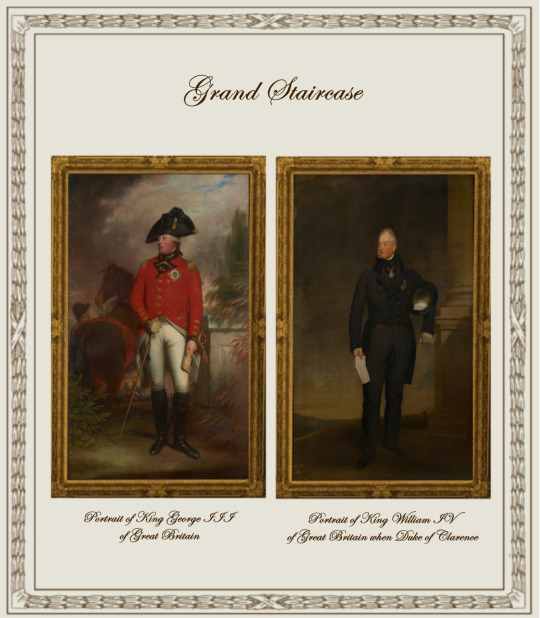

Grand Staircarse (GS):

Portrait of Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, Queen Consort of Great Britain (Martin Archer Shee)

Portrait of Augustus, Duke of Sussex (Sir David Wilkie)

Portrait of Edward, Duke of Kent (George Dawe)

Portrait of King George III of Great Britain (Sir William Beechey)

Portrait of King William IV of Great Britain when Duke of Clarence (Sir Thomas Lawrence)

Portrait of Leopold I, King of the Belgians (William Corden the Younger)

Portrait of Prince George of Cumberland, Later King George V of Hanover When a Boy (Sir Thomas Lawrence)

Portrait of Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales (George Dawe)

Portrait of Queen Charlotte at Frogmore House (Sir William Beechey)

Portrait of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafeld, Duchess of Kent (Sir George Hayter)

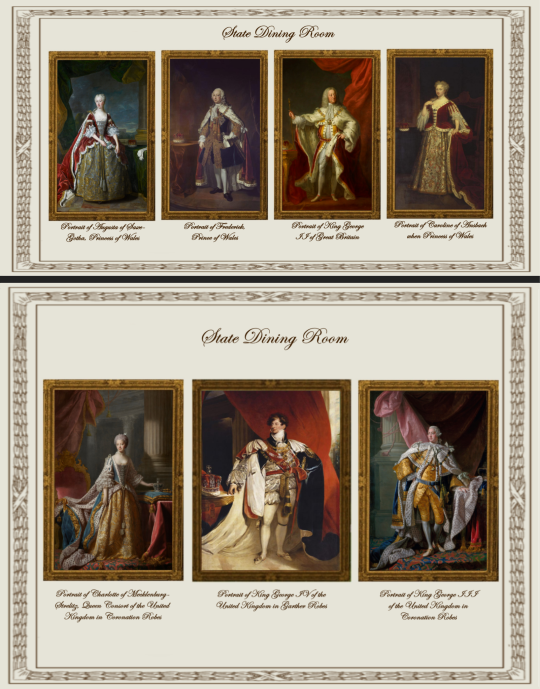

State Dining Room (SDR):

Portrait of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen Consort of the United Kingdom in Coronation Robes (Allan Ramsay)

Portrait of King George III of the United Kingdom in Coronation Robes (Allan Ramsay)

Portrait of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, Princess of Wales (Jean-Baptiste Van Loo)

Portrait of Caroline of Ansbach when Princess of Wales (Sir Godfrey Kneller)

Portrait of Frederick, Princes of Wales (Jean-Baptiste Van Loo)

Portrait of King George II of Great Britain (John Shackleton)

Portrait of King George IV of the United Kingdom in Garther Robes (Sir Thomas Lawrence)

Queen's Audience Room (QAR):

Portrait of Anne, Duchess of Cumberland and Strathearn (née Anne Luttrel) in Peeress Robes (Sir Thomas Gainsborough)

Portrait of Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn in Peer Robes (Sir Thomas Gainsborough)

London: The Thames from Somerset House Terrace towards the City (Giovanni Antonio Canal "Canaletto")

View of Piazza San Marco Looking East Towards the Basilica and the Campanile (Giovanni Antonio Canal "Canaletto")

Blue Drawing Room (BDR)

Portrait of King George V in Coronation Robes (Sir Samuel Luke Fildes)

Portrait of Queen Mary of Teck in Coronation Robes (Sir William Samuel Henry Llewellyn)

-------------------------------------------------------

Found under decor > paintings for:

500§ (WDR: 1,2 & 3)

1850§ (GDR: 1)

1960§ (GDR: 2 & 3 |QAR 3 & 4)

3040§ (STR, 1 |GC: 1 & 2|SDR: 1 & 2)

3050§ (GC:1 |GS: all 10|WDR: 4 |SDR: 3,4,5 & 6)

3560§ (QAR: 1 & 2|STR: 2)

3900§ (SDR: 7| BDR: 1 & 2|GDR: 4,5,6 & 7)

Retextured from:

"Saint Mary Magdalene" (WDR: 1,2 & 3) found here .

"The virgin of the Rosary" (GDR: 1) found here .

"The Four Cardinal Virtues" (GDR: 2&3|QAR 3 & 4) found here.

"Mariana of Austria in Prayer" (STR, 1, GC: 1 & 2|SDR: 1 & 2) found here.

"Portrait of Philip IV with a lion at his feet" (GC:1 |GS: all 10|WDR: 4 |SDR: 3,4,5 & 6) found here

"Length Portrait of Mrs.D" (QAR: 1 & 2|STR: 2) found here

"Portrait of Maria Theresa of Austria and her Son, le Grand Dauphin" (SDR: 7| BDR: 1 & 2|GDR: 4,5,6 & 7) found here

(you can just search for "Buckingham Palace" using the catalog search mod to find the entire set much easier!)

Drive

(Sims3pack | Package)

(Useful tags below)

@joojconverts @ts3history @ts3historicalccfinds @deniisu-sims @katsujiiccfinds @gifappels-stuff

-------------------------------------------------------

#the sims 3#ts3#s3cc#sims 3#sims 3 cc#sims 3 download#sims 3 decor#edwardian#rococo#baroque#renaissance#buckingham#buckingham palace#royal collection trust#wall decor

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

An interesting find in a letter from Elizabeth Stuart, the former Queen of Bohemia, to her son Karl Ludwig, dated 14/24 June 1658 showing one of the earliest uses of the word "redcoat" for English (later, British) troops I have seen so far.

The battle referred to is the Battle of Dunkerque of 3 June 1658 and her "deare Godsonne" is James, Duke of York, the future King James II.

#elizabeth stuart#elizabeth of bohemia#military history#17th century#letters#karl ludwig von der pfalz#james ii#history

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

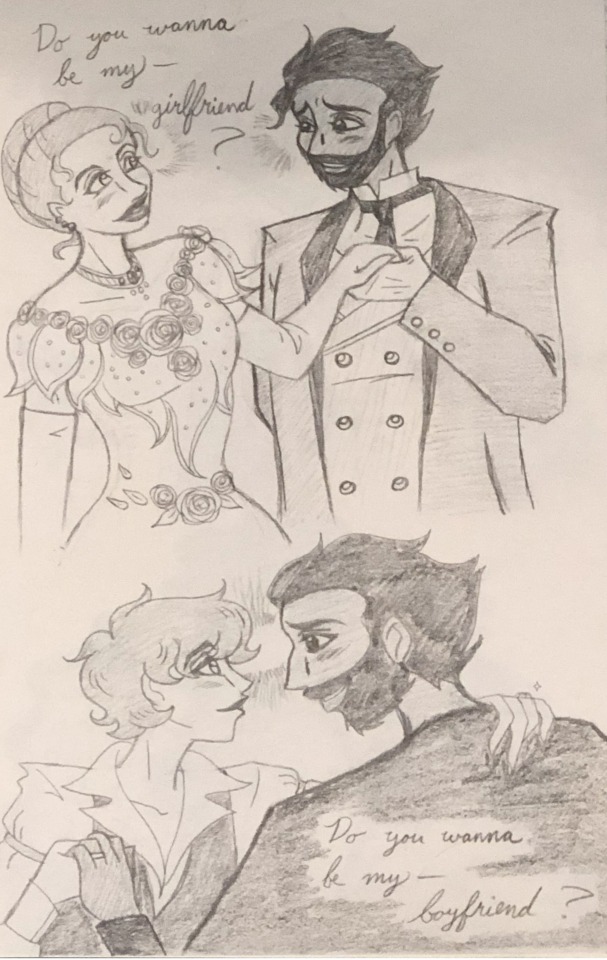

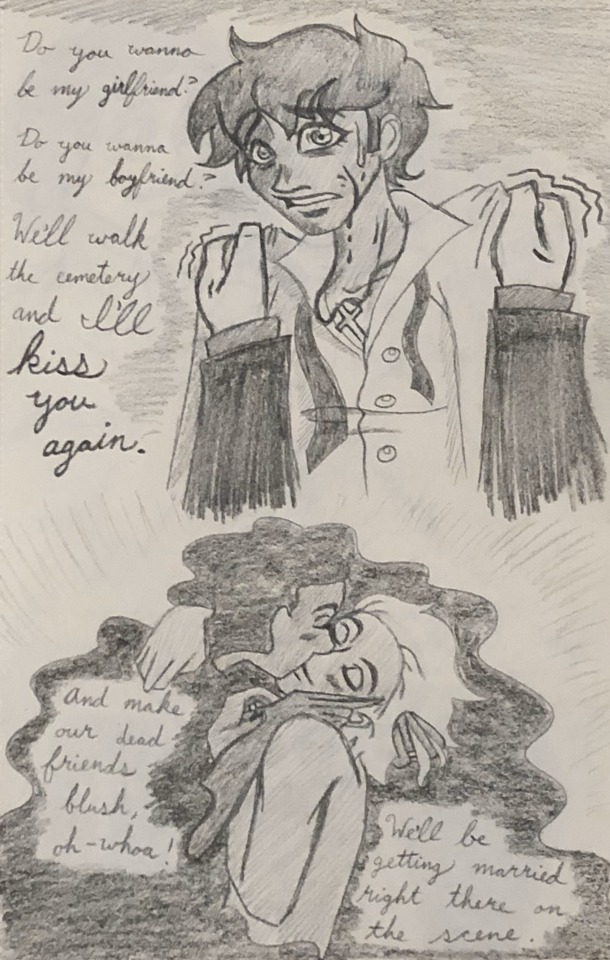

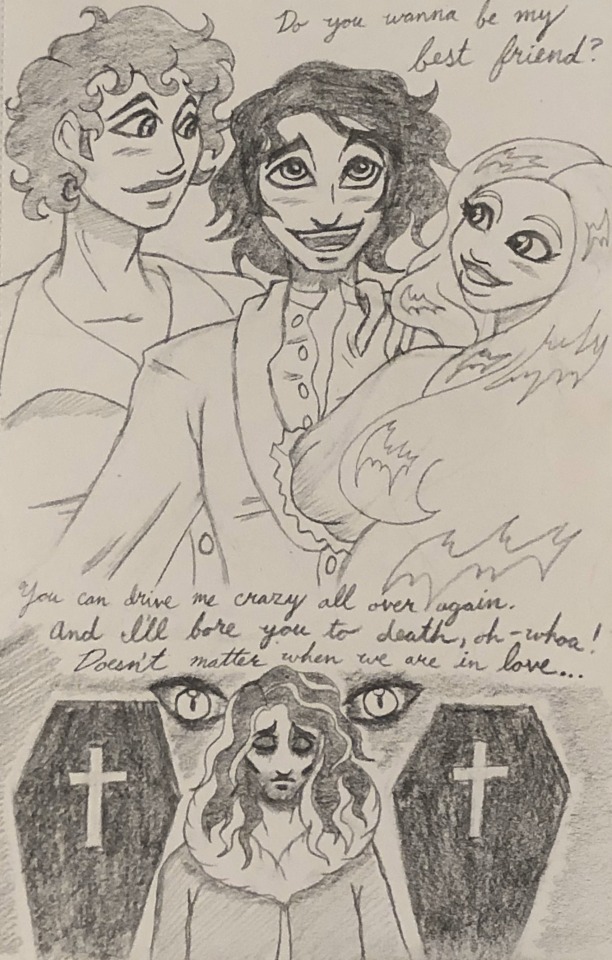

Do you wanna be my boyfriend?

Do you wanna be my boyfriend?

Do you wanna be my boyfriend?

Do you wanna be my boyfriend?

You're not just any type of girl

My one true love

And you're my world

Something about the nebulous nature of gender across three of my favorite classic characters and the ones who love* them.

*Love here including the good, the bad, and the gothic.

Pictured top to bottom:

Irene Norton, formerly Adler, and Godfrey Norton of Sherlock Holmes' "A Scandal in Bohemia"

Jonathan Harker, Dracula, and Mina Harker, of Dracula

Henry Clerval, Victor Frankenstein, Elizabeth Lavenza, and the Creature, of Frankenstein

#this album is eating holes in my brain#irene adler#godfrey norton#sherlock holmes#jonathan harker#mina harker#dracula#victor frankenstein#henry clerval#elizabetha lavenza#the creature#frankenstein#green day#bobby sox#genderfluid#trans#biromantic#bisexual#pansexual#lgbtqa#my art

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Queens at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. For this reason, women such as Philippa of Hainault and Anne Boleyn have been omitted.

This list is composed of Queens of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. Using the youngest possible age for each woman, the average age at first marriage was 17.

Eadgifu (Edgiva/Ediva) of Kent, third and final wife of Edward the Elder: age 17 when she married in 919 CE

Ælfthryth (Alfrida/Elfrida), second wife of Edgar the Peaceful: age 19/20 when she married in 964/965 CE

Emma of Normandy, second wife of Æthelred the Unready: age 18 when she married in 1002 CE

Ælfgifu of Northampton, first wife of Cnut the Great: age 23/24 when she married in 1013/1014 CE

Edith of Wessex, wife of Edward the Confessor: age 20 when she married in 1045 CE

Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror: age 20/21 when she married in 1031/1032 CE

Matilda of Scotland, first wife of Henry I: age 20 when she married in 1100 CE

Adeliza of Louvain, second wife of Henry I: age 18 when she married in 1121 CE

Matilda of Boulogne, wife of Stephen: age 20 when she married in 1125 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE, and later Geoffrey V of Anjou: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Eleanor of Aquitaine, first wife of Louis VII of France and later Henry II of England: age 15 when she married Louis in 1137 CE

Isabella of Gloucester, first wife of John Lackland: age 15/16 when she married John in 1189 CE

Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of John Lackland: between the ages of 12-14 when she married John in 1200 CE

Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III: age 13 when she married Henry in 1236 CE

Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I: age 13 when she married Edward in 1254 CE

Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I: age 20 when she married Edward in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, wife of Edward II: age 13 when she married Edward in 1308 CE

Anne of Bohemia, first wife of Richard II: age 16 when she married Richard in 1382 CE

Isabella of Valois, second wife of Richard II: age 6 when she married Richard in 1396 CE

Joanna of Navarre, wife of John IV of Brittany, second wife of Henry IV: age 18 when she married John in 1386 CE

Catherine of Valois, wife of Henry V: age 19 when she married Henry in 1420 CE

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI: age 15 when she married Henry in 1445 CE

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Sir John Grey and later Edward IV: age 15 when she married John in 1452 CE

Anne Neville, wife of Edward of Lancaster and later Richard III: age 14 when she married Edward in 1470 CE

Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII: age 20 when she married Henry in 1486 CE

Catherine of Aragon, wife of Arthur Tudor and later Henry VIII: age 15 when she married Arthur in 1501 CE

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII: age 24 when she married Henry in 1536 CE

Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII: age 25 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Catherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII: age 17 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Jane Grey, wife of Guildford Dudley: age 16/17 when she married Guildford in 1553 CE

Mary I, wife of Philip II of Spain: age 38 when she married Philip in 1554 CE

Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI & I: age 15 when she married James in 1589 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I: age 16 when she married Charles in 1625 CE

Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II: age 24 when she married Charles in 1662 CE

Anne Hyde, first wife of James II & VII: age 23 when she married James in 1660 CE

Mary of Modena, second wife of James II & VII: age 15 when she married James in 1673 CE

Mary II of England, wife of William III: age 15 when she married William in 1677 CE

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

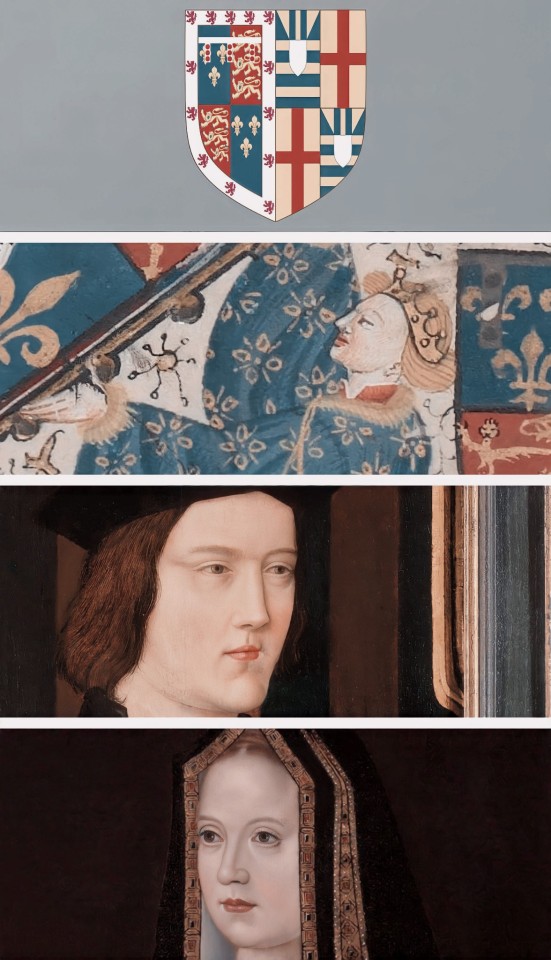

⋆ William, The Conqueror to William, The Prince of Wales ⋆

⤜ The Prince of Wales is William I's 24th Great-Grandson via his paternal grandmother's line.

William I of England

Henry I of England

Empress Matilda

Henry II of England

John of England

Henry III of England

Edward I of England

Edward II of England

Edward III of England

Lionel of Antwerp, Ist Duke of Clarence

Philippa Plantagenet, Vth Countess of Ulster

Roger Mortimer, IVth Earl of March

Anne Mortimer

Richard Plantagenet, IIIrd Duke of York

Edward IV of England

Elizabeth of York

Margaret Tudor

James V of Scotland

Mary Stewart, Queen of Scotland

James I of England

Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia

Sophia, Electress of Hanover

George I of Great Britain

George II of Great Britain

Frederick, Prince of Wales

George III of the United Kingdom

Prince Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

George V of the United Kingdom

George VI of the United Kingdom

Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

Charles III of the United Kingdom

William, The Prince of Wales

#royal line from william i#the british royal line#british royal family#british royals#royalty#royals#british royalty#brf#royal#royalty edit#mine.#historical royals#prince william#prince of wales#the prince of wales#william the conqueror#king edward iv#the plantagenets#house of york#house of plantagenet#house of tudor#house of stewart#house of stuart#king charles#king charles iii#queen elizabeth ii#queen victoria#house of normandy#mary queen of scots

168 notes

·

View notes

Note

what did cicely neville do in edward iv's reign?

Hi! Cecily’s entire role during Edward IV’s reign is too long and complex to fully get into right now, so this is just going to be a very brief overview. It’s also not going to touch on her relationship with her daughter-in-law Elizabeth, even though that's somewhat relevant here in some aspects, because that’s also too complex and speculatory.

Ironically, despite the Duke of York’s claims to kingship, it was only after his death and during her widowhood that Cecily Neville truly emerged as a “quasi-queen”. After her son Edward IV had been acclaimed as King in London, and before he left for Towton with the other lords, he summoned the mayor and “all the notables of London” to gather and “recommended them to the duchess his mother”. During his absence, Cecily would preside over his household in Baynard Castle and was probably meant to act as his representative of sorts in the city. After his kingship was more firmly established, Cecily primarily resided at Westminster with him from 1461-64 and regularly accompanied him on several ceremonial and political occasions, such as their visit to Canterbury where she was magnificently welcomed. She also appears to have had a great deal of personal and political influence with her son: Nicholas O’Flanagan, the contemporary Bishop of Elpin, observed in the first few years of Edward IV's reign, his mother could “rule the king as she pleases.”

Cecily’s role demonstrably changed after Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville in 1464. She remained the second-highest ranked woman in the country, but she took a significant step back from high politics (a la Joan of Kent after her son’s marriage to Anne of Bohemia). That does not mean that either of them suddenly became apolitical or uninvolved: quite the opposite*. Cecily remained the head of a large household, her administration supported her son’s, she continued to support a few religious institutions, she engaged in trade, she launched court cases, and she clearly inspired loyalty among her affinity. All of this was fairly standard for a medieval noblewoman, but was naturally enhanced by Cecily’s own prominent royal status. Cecily was godmother to at least three of the royal children: Elizabeth of York, her namesake Cecily, and the youngest child, Bridget. She also played a role in reconciling her son George to the Yorkist cause in 1471, though she did not have the spearheading role which has often been erroneously credited to her by historians (ie: “engineering peace between her warring sons”); instead, it was her daughters Anne and Margaret who took the leading role in achieving the reconciliation, while Cecily probably aided them. She was also clearly perceived to be influential with Edward IV, best evidenced by how the mayors of Norwich petitioned her to aid them against the Duke of Suffolk in 1480, though we don’t actually know the result of Cecily’s intervention to judge whether it succeeded or how effective it was**. Regardless, though, she evidently had a much lower national profile during these years.

(On a more personal level, we also have a very sweet anecdote from Elizabeth Stonor who spoke of a meeting between Cecily and Edward in October 1476 at Greenwich: 'and ther I sawe the metyng betwyne the Kynge and my ladye his Modyr. And trewly me thowght it was a very good syght’.)

Cecily’s numerous titles are also interesting. Immediately after Edward IV’s ascension, she called herself “the Kyngs Moder, Duchess of York”. Variations of the title included references to her late husband, but she primarily defined herself in relation to her son, through whom her current position and power derived. As Laynesmith says: "narrative accounts, particularly chronicles, had naturally used the phrase ‘the king’s mother’ to describe women in the past, especially Joan of Kent. However, it was Cecily who turned this into a specific title in her letters and on her seals." A few months after Edward's marriage was announced, Cecily adopted a new title, now styling herself as: “By the ryghtful enheritors Wyffe late of the Regne off Englande & of Fraunce & off ye lordschyppe off yrlonde, the kynges mowder ye Duchesse of Yorke.” This referenced the Yorkist perception of her husband, Richard Duke of York, who was called the "true and indubitable heir" of England. In 1477, a herald for the wedding of her grandson Richard of Shrewsbury styled Cecily as “the right high and excellent Princesse and Queene of right, Cicelie, Mother to the Kinge”. This was once again linked to her husband’s status: Cecily described him in her letters as “in right King of England and of France and lord of Ireland”. All in all, Cecily’s various designations appear to have been designed to signify her own importance within the regime, to uphold the claim of her late husband, and to strengthen Edward IV’s position by promoting him as the son of the supposedly rightful heir. It’s also very possible, as Laynesmith has suggested, that “it was as her queenly power diminished [after the early 1460s] that her claims to queenship were more elaborately emphasized in wax and on parchment”.

Cecily’s role and prominence, and how it changed overtime, is best demonstrated by the number of times English subjects offered prayers for her soul in return for grants. Between June 1461 and September 1464, there are twelve instances of grants made to people who offered prayers for her. (To compare, during the first three years of Elizabeth Woodville's queenship, there were sixteen grants of the same type. So, Cecily didn't quite reach the level of the queen, but she came close; it was quintessential "quasi-queenship"). However, mentions of Cecily dramatically deceased following Edward IV's marriage: over the next 19 years till 1483, she is only mentioned five times, and in all cases Elizabeth Woodville was also listed before she was. Three of these mentions are in 1465, likely reflecting contemporary unease with her son's controversial marriage and the perceived unsuitable origins of the new queen. After that, however, Cecily is mentioned only twice: once in 1476 and once in 1481, with the latter being a grant to her own son-in-law Thomas St. Leger***. This fits well with what I mentioned above about her quasi-queenship in the early 1460s, followed by a much more reduced role and lower national profile in the future years.

Hope this helps!

*Oddly, Cecily is not mentioned at all in contemporary reports for her daughter Margaret’s wedding. Laynesmith believes that she was unwell, and that may as well be true, but Margaret's celebrations went on for a great period of time and it does seem conspicuous that Cecily was entirely absent from them all. It's also worth noting that a letter from the Milanese ambassador Giovanni Pietro Panicharolla on the marriage wrote that "the king, the queen, her father, and the king's brothers are all disposed to it" (sidenote: it's VERY interesting that the queen's father is mentioned before the king's own brothers and male heirs) but made no mention of Cecily. Nor, iirc, was she mentioned in the tournament held to celebrate Anglo-Burgundian relations. It does clearly seem as though Cecily did not play a notable role in the marriage, and relevant diplomacy, at all. (Laynesmith's claim that Cecily had "helped lay the ground for" the marriage because she *checks notes* dispatched both her sons to Burgundy in middle of a civil war 7 years earlier, with many fluctuations in Anglo-Burgundian relations in between, is, I'm sorry to say, nonsense).

** Laynesmith believes that "Cecily’s intervention to control Suffolk perhaps marked a turning point in the duke’s violent career because when he resorted to force again the following summer his victim successfully reclaimed the manor from which he had personally ejected her." I think that Laynesmith is being far too assumptive and that we don’t even know the result of Cecily’s intervention in 1480 to somehow credit her with entirely different case one year later that did not even involve her, lol.

***Even more oddly, Cecily’s own son Richard didn’t include her among the list for who to offer prayers for in his college in Middleham in 1478. This was despite the fact that he had included Edward IV, Elizabeth Woodville, his wife Anne, his sisters, his dead brothers and his dead father. It’s incredibly striking, and I wonder what could have happened to cause her exclusion, especially since she was included in religious foundations by both Edward and her son-in-law Thomas St. Leger? Laynesmith claims that "this rather suggests that Richard's own piety was not consciously influenced by hers", and sure, that seems obvious, but it certainly can't have been the only reason. Was she merely overlooked (unlikely), or did they have a quarrel at the time, or was it for another now-unknown reason? Whatever the case, it's a small but intriguing detail to me.

Sources:

"Cecily, Duchess of York" by J.L. Laynesmith

"A Paper Crown: The Titles and Seals of Cecily, Duchess of York" by J.L. Laynesmith (The Ricardian)

"Cecily Neville: Mother of Kings" by Amy License

26 notes

·

View notes