#Craiglockhart

Photo

Colinton Grove, EH14

#Colinton Grove#Craiglockhart#Edinburgh#Scotland#United Kingdom#Street Photography#Photographers on Tumblr#2023

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It would suck to be a ghost at Craiglockhart. You're some poor war veteran or something and thought you had a nice manor house to reside in, but no you get to share with a business school of all things and watch 200 young people enter The Egg and learn about Capitalism

0 notes

Text

Craiglockhart

Brian Johnstone

Maybe they’re here somewhere, lost

in these crowds of students, informal

in their tweeds, plus fours –

Sassoon, the elder, Sunday golfer;

Owen, bookish, gangly, pale – mingling

with the queue for the refectory,

snatching nervously at fags, ignoring

notices forbidding all those here

to smoke. You catch a glimpse

you think, later, in the distance

– backs straight, military haircuts –

turning down a corridor you glance along

but they’re not there. No, no-one is, though

low light slants through window frames,

plants these crosses on the wall.

#poetry#war poets#WWI#craiglockhart#military hospital#shell shock#neurasthenia#brian johnstone#sassoon#owen#graves

0 notes

Text

CATHERINE'S STYLE FILES - 2021

27 MAY 2021 || The Countess of Strathearn paid a visit to the Craiglockhart Tennis Centre in Edinburgh along with the Earl on their fourth day in Scotland.

#catherines style files#style files 2021#mine.#craiglockhart tennis centre edinburgh visit 21#lta youth#duchess of cambridge#catherine cambridge#27.05.2021#scotland visit may 21#day 4 scotland visit may 21#ralph lauren.#superga.#cotu sneakers#daniella draper.#gold fixed alphabet necklace#orelia london.#chain huggie hoop earrings#british royal family#british royals#brf#british royalty#catherine middleton#kate middleton#royalty#royals#royal#royal fashion#fashion#style#lookbook

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

watched the sass movie and didnt like it but i have the violent need to talk shit abt it to my thesis director

#i just think that sass deserved to do more than#argue w a revolving door of cruel lovers#and never brought up his war exp#except in generic footage#and that his poetry should have been better selected#or really just#everyone sang should be in there#giving wilfred owen the last word in a siegfried sassoon biopic#after barely representing craiglockhart#OOF.#arms and the bri

0 notes

Text

Edinburgh Castle.

From the summit of Easter Craiglockhart Hill.

Not a great pic, and from my phone, it's a bit murky around Edinburgh today, I will need to head up with a camera on a better sunny day.

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fic authors self rec! When you get this, reply with your favorite five fics that you've written, then pass on to at least five other writers. Let’s spread the self-love 💗

Thanks for the ask! For my five:

The Saint’s Blade is definitely my favourite fic, and one of my favourite things I’ve written overall. A series of interconnected stories about Sophia Hess going into another world which worships Worm capes as gods – becoming a paladin – and falling in love in the process. The opportunity to world-build was wonderfully fun, the OC cast great to work with, and it gave an interesting chance to play with Soph’s character to boot.

No Greater Love is the other longer fic from my more recent Worm stuff which I’m proud of, where Taylor gets dropped into a universe where her alter-ego is a Ward, dating Shadow Stalker…and has just been killed in action. I particularly enjoyed writing the aftermath of Taylor’s death in the first chapter, tackling it from three different perspectives – the casualty notification officer, her mom, and her girlfriend – and exploring the nuances as a result.

While I really enjoy a lot of my Legend of Korra and ATLA fic, Kuvira’s Diary in the Advance to Ba Sing Se, 171 AG is one I particularly liked writing. As the title suggests, it is verbatim Kuvira’s diary from the point of leaving Zaofu to her securing Ba Sing Se and being empowered by the other nations to re-unify the Earth Kingdom. Writing an early, not-jaded Kuvira was great fun – particularly as I was able to sow the seeds of what she later became throughout – while the worldbuilding of the Earth Kingdom sinking into anarchy and depredation was an enjoyable exercise.

Balestra, co-written with the wonderful maroon_sweater, was unquestionably the most fun I’ve ever had writing a fanfic. In premise, it was an epistolary enemies to lovers romance inspired by This Is How You Lose The Time War. In execution, it was her and I writing each other condescending hate mail on a daily basis for a month – really quite fantastic. This is only uplifted by the fact that Roon is an incredibly talented writer, deeply and dryly witty in a way which never ceases to impress; trying to keep up with her alone was an engaging challenge.

When We Are Dust, my collection of Worm WW1 AU snippets, is a fic I often go back to read – especially ‘All His Evermore’, about General Hana Kochar of the Kurdish Republic, ‘Inherent to Circumstance’ about Shatterbird, leader of the Arab Revolt, and ‘Et Decorum Est’ about Captain Dean Stansfield in Craiglockhart mental hospital. Translating the characters into the historical setting was an engaging challenge, and the AU fit my penchant for both military detail and big emotional moments. I’m also proud of the writing; the last line, in particular – ‘As for the dead? They remain, fixed and unmoving down the centuries. Like stars, when we are dust.’

Tagging @cpericardium @therealtsk @orangepanic @wishingforatypewriter and @crookedmouth-mountainbones and anyone else who wants to join in!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

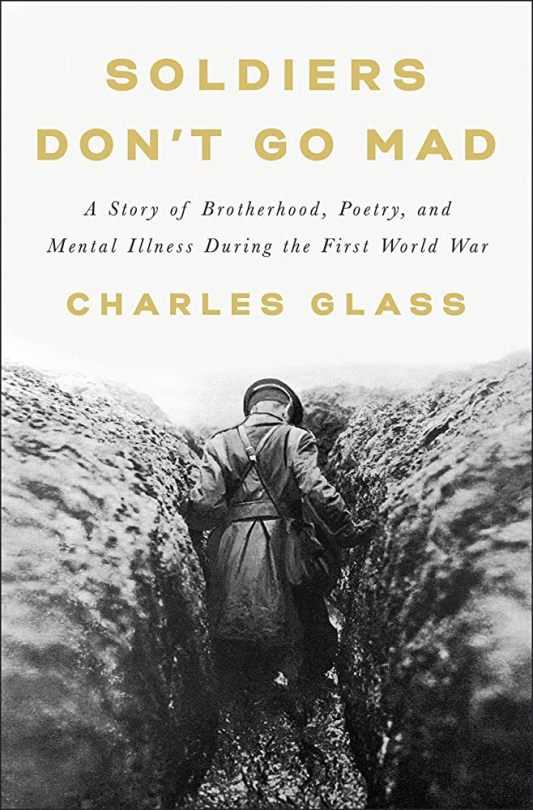

“A riveting history of Scotland’s Craiglockhart War Hospital, a progressive and peculiar oasis for British officers at a time when mental illness among soldiers was all too often dismissed as cowardice. Charles Glass chronicles the lives of the shell-shocked, from the poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen to uncelebrated men whose stories demand our attention, and devotes the same nuance and grace to their deeply compassionate physicians. Soldiers Don’t Go Mad is a timely, essential reminder that wars carry on well beyond the truces and treaties that formally end them.”

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Storia Di Musica #293 - The Waterboys, Fisherman's Blues, 1988

And I am the Water Boy\The real game’s not over here. Nel 1973 Lou Reed pubblica Berlin, album seminale, oscuro, profondissimo e nella canzone The Kids compare il verso che ho appena scritto. Sarà lo spirito scozzese, così abituato alla poetica e selvaggia bellezza di quella terra, ma come per la vicenda dei Deacon Blue quel verso diviene una scheggia di passione che colpisce lo spirito di un giovane ragazzo di Edimburgo, che si appassiona alla musica. La capitale scozzese è tutt’altra città rispetto a Glasgow e ha dei particolari piuttosto noti a noi, dato che è attraversata da un fiume (anzi sorge all'insenatura (firth) creata dall'estuario del fiume Forth) e si sviluppa su sette colli (Arthur’s Seat, Calton Hill, Castle Rock, Corstorphine Hill, BVarids Hill, Blackford Hill, Craiglockhart Hill). Mike Scott è un poeta e cantante di Edimburgo, che per un po’ di tempo vive a Ayr, sulla costa occidentale della Scozia. Nel 1977 fonda una fanzine, una rivista autoprodotta dedicata ai propri idoli musicali, e il titolo, Jungleland, porta subito a pensare a Springsteen, Dylan, l’astro nascente in quegli anni Patti Smith. Istrionico, fonda un gruppo, gli Another Pretty Face e una etichetta discografica, la Chicken Jazz, che subito viene acquistata dalla Virgin di Richard Branson, che vedrà in questo ragazzo del potenziale altissimo, e non sbaglierà, dato che Scott sarà personaggio dai complessi risvolti e una delle figure più interessanti del panorama musicale degli anni ’80. Dopo varie esperienze, tra cui delle serate con Lenny Kane a New York, torna in Inghilterra e decide che chiamerà il suo gruppo The Waterboys proprio in omaggio alla canzone di Lou Reed.

Eppure musicalmente ci sono delle profonde differenze rispetto a quel disco mitico: Scott è affascinato da una certa idea di folk con contaminazioni rock, già fatta da gruppi leggendari come i Fairport Convention di Richard Thompson negli anni ' 60 e ’70. Il primo nucleo dei The Waterboys era composto dal sassofonista Anthony Thistlethwaite, Norman Rodger al basso, Karl Wallinger alle tastiere, Preston Heyman alla batteria oltre a Scott che suona la chitarra, il mandolino e altri strumenti. Con questa formazione si presentano ad una famosa Peel Session nel 1983 alla BBC, dove suonano il loro primo successo, A Girl Called Johnny, brano tributo a Patti Smith che entrerà a far parte nel luglio dello stesso anno di The Waterboys: già c’è la miscela interessantissima di musica in bilico tra folk e rock, equidistante da Van Morrison e dal rock epico post new wave. Più rock è A Pagan Place, del 1984, famoso per un brano, Church Not Made With Hands. Scott è ancora alle prese con una sua definizione di musica, anzi di una “big music”, che si leghi sia alla tradizione, ma che abbia un tocco personale unico e distintivo. Si ritira ai Park Gates Studio di Hastings, celebre luogo di una battaglia, ed inizia a pensare alla sua visione della musica, che parte sempre dal misticismo caledonico di Van Morrison ma stavolta vira con decisione verse le tinte fosche dei Velvet Underground, fino alla musica minimale (Scott dichiarerà di essersi ispirato a Steve Reich). This Is The Sea (1985) seppur con brani registrati in presa diretta, è un sottile gioco di strumenti e voci sovrapposte, in una rielaborazione in chiave celtica del wall of sound spectoresco, con l’aggiunta di testi profondissimi, che affascinarono un’intera generazione di musicisti. Il risultato è splendido. Ma Scott è tipo lunatico e quando sembra sul punto di spiccare definitivamente il volo, si prende una nuova lunga pausa dove, spostandosi a Dublino, inizia a rielaborare i suoi capisaldi. Si tuffa nella musica popolare e tradizionale di Scozia e Irlanda, e con l’aiuto di nuovi innesti, centrale quello di Steve Wickham al violino, nel 1988 pubblica il capolavoro atteso, uno dei dischi più belli degli anni 80.

Fisherman’s Blues è un album folk, ma che dalla tradizione si muove con estrema eleganza verso sonorità fresche, nuove, in un connubio che solo la genialità di Scott poteva costruire. L’apertura con la title track già da sola è euforia e classe, come la lunga e ipnotica We Will Not Be Lovers, tutta giocata su un riff di violini (canzone iconica). Le onde dell’oceano, le colline verdi, i muretti di pietra a delimitare i pascoli, i colori selvaggi e accesi sono sempre lì, tra una strepitosa cover di Sweet Thing di Van Morrison (da Astral Week) e addirittura il folk politico di This Land Is Your Land di Woody Guthrie. La musica da pub irlandese esplode nella stupenda And A Bag On The Ear (che è l’equivalente irlandese per un bacio sulla guancia italiano) che parla di un amore nato sui banchi di scuola. E come non adorare il sottile andare di When Will We Be Married. Se non si è ancora sazi di colline verdi smeraldo, atmosfere con l’odore tostato di birra stout, dell’affumicato di un single malt torbato e di semi di lino da sgranocchiare, c’è il colpo di grazia: un duetto tra Scott e Tomás Mac Eoin, uno dei più famosi cantanti di Sean-nós, che è un particolare stile di canto gaelico irlandese, che recitano e cantano William Butler Yeats nella indimenticabile The Stolen Child. Scott registrò così tanto materiale che solo nel 2006 ripubblicò l’album con la sua intera idea, che comprendeva ancora cover di Dylan, traditional e altre piccole meraviglie (tipo Let Me Feel Holy Again o l’altrettanto strepitosa You In The Sky). Scott, chiamato da attese spasmodiche, ritornò con lo stesso stile musicale nel 1990 con Room To Roam, che nei piani del cantante, risponde appieno all'attuale percorso musicale, che in onore al traditional The Raggle Taggle Gypsy Scott definisce raggle taggle music. Poi, inaspettatamente, virò verso un suono quasi hard rock (Dream Harder, nome omen, del 1993). E dopo una virata così inaspettata, ecco che, nella sua migliore tradizione personale, scioglie il gruppo e si prende l’ennesima e stavolta davvero lunghissima pausa, un decennio fino al 2000 quando ritorna a scrivere insieme ad altri musicisti nuovi capitoli di una saga nata 20 anni prima. Un geniale lunatico.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

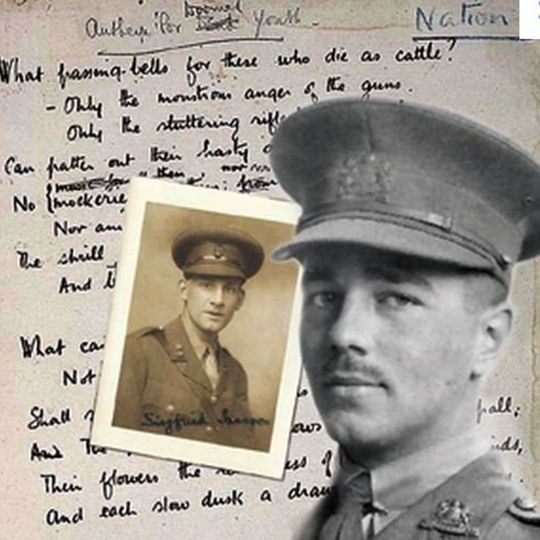

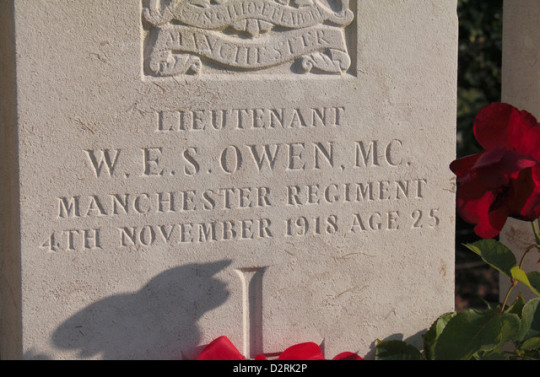

Wilfred Owen: the man not the memorial

All a poet can do today is warn.

- 2nd Lieutenant Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (1893-1918)

The body of Wilfred Owen’s work is generally regarded as a memorial to the atrocities of war. Often heralded as one of the finest poets of the First World War, Wilfred Owen has become a symbol to many of 1914-1918 encapsulating a sense of futility (the title one of his more famous poems), anger, and despair at the suffering endured by the soldiers during the Great War, or indeed any war before and after.

Poems like ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’ convey the intense futility of it all, for “what passing-bells for these who die as cattle?”, whilst he evokes the disturbing psychological impact of the fighting in works like ‘Mental Cases’ where “these are the men whose minds the Dead have ravaged”. The canonisation of such works has preserved Owen as a symbol of the First World War and a reminder of its horrors.

This is not without challenge of course. Owen’s was only one voice representing one point of view and cannot be seen to capture the myriad of views and feelings of all the combatants and his generation, but at the same time that is not sufficient reason to dismiss his work as irrelevant to the study of the War.

More interesting to me is the feeling that Owen’s poetic legacy has put aside the man that was Wilfred Owen. Every schoolchild knows at least one of his poems but know very litte of his life as a man and as a soldier. It is easy to forget that he too was a flesh and blood man fighting in the trenches, with his own hopes and fears, uncertainties and complexities.

Born in 1893, Owen was teaching English to children near Bordeaux, France, when war broke out in the summer of 1914. The following year, he returned to England and enlisted in the war effort. On 21 October 1915, he enlisted in the Artists Rifles Officers' Training Corps. For the next seven months, he trained at Hare Hall Camp in Essex. On 4 June 1916 he was commissioned as a second lieutenant (on probation) in The Manchester Regiment. By January 1916 he was on the front lines in France. As he wrote in 1918, his motives for enlisting were twofold, and included his desire to write of the experience of war: “I came out in order to help these boys - directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly, by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a pleader can.”

On April 1, 1917, near the town of St. Quentin, Owen led his platoon through an artillery barrage to the German trenches, only to discover when they arrived that the enemy had already withdrawn. Severely shaken and disoriented by the bombardment, Owen barely avoided being hit by an exploding shell, and returned to his base camp confused and stammering.

A doctor diagnosed shell-shock, a new term used to describe the physical and/or psychological damage suffered by soldiers in combat. Though his commanding officer was skeptical, Owen was sent to a French hospital and subsequently returned to Britain, where he was checked into the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Neurasthenic Officers in Scotland in 1917. There he was officially diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia (‘shell-shock’).

It was there he famously met Siegfried Sassoon and his poetry took on a new direction and life. Owen spent the first part of 1918 in England training and recuperating. He did a short spell working as a teacher in nearby Tynecastle High School, he returned to light regimental duties. In March 1918, he was posted to the Northern Command Depot at Ripon. A number of poems were composed in Ripon, including "Futility" and "Strange Meeting". His 25th birthday was spent quietly in Ripon Cathedral.

In recent years much work has been done to restore Owen’s humanity, most notably Dominic Hibberd’s 2002 work Wilfred Owen: A New Biography, which, whilst clearing up other details of Owen’s life, confirms that he was gay. On one level that shouldn’t matter. But interestingly facts like this could cast some of his poetry in a new light, with particular regard to the vivid and sometimes shocking sensuality and even excitement that is undoubtedly present in poems like ‘The Sentry’, where “thud! flump! thud! down the steep steps came thumping/ And splashing in the flood, deluging muck”. An idea of the attractiveness and lure of war could possibly develop from this interpretation, particularly as Owen, like his friend Siegfried Sassoon, returned to the front line after absence.

Indeed whilst Owen's work rises above that of many contemporary poets, the circumstances surrounding his death at such a young age (25), and the news of his death, has added to the powerful emotions that surround Owen. Rejecting offers by his friends to pull strings and arrange for him to sit out the rest of the war Owen chose to return to the front to help the men he felt he had left behind. Owen’s battalion was part of the spearhead used to break the final German defensive line after a series of Allied advances following success at Amiens in August 1918. On 1 October 1918, Owen led units of the Second Manchester's to storm a number of enemy strong points near the village of Joncourt. For his courage and leadership in this action, he was awarded the Military Cross.

Owen was killed in action on 4 November 1918 during the crossing of the Sambre–Oise Canal, exactly one week (almost to the hour) before the signing of the Armistice which ended the war, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant the day after his death. A key problem was to overcome the Sambre canal defences and gain the Eastern bank, and on 4th November at 5.45am Owen was involved in the attempt to cross. The exact details of that morning are hazy, and all that is known is that Owen was seen leading and encouraging his men in the early part of the struggle, but was killed, possibly as he crossed the water on a raft, sometime between 6 and 8.00am. Famously the telegram notifying his family of his death arrived mid-day on November 11th as the celebrations around the Armistice rang out.

These are facts known to all of us. But what I found really eye opening was going to the place where he spent his last night before his death. It puts a different perspective on Wilfred Owen, not the poet, but the man and the officer who cared deeply for his men under his command.

Owen and his platoon had spent the previous night in the cellar of a Forester’s House in the wood outside Ors. Ors is mere two hours’ drive from Calais in the Nord-Pas de Calais region. It’s a small village and if you walk across the canal you can church bells tolling. To right and left the countryside resembles a French Impressionist painting. The waterway is lined with tall, leafy Poplar trees; there are meadows full of cattle, the hills beyond roll into the distance - an idyllic scene, glowing in the spring sunlight. It’s hard to conceive of the ghastly sights, sounds and smells that once shattered this tranquil landscape.

When I was driving with friends around there we visited key sites that marked the First World War. When we got to Ors we came across Forester’s House, now a memorial to Wilfred Owen. We were told by that by some villagers that a great number of British visitors came looking for Owen’s grave and the exact spot where he had been killed, and asking to visit the cellar of the Forester’s house. And so a grassroots campaign amongst locals began to raise funds to commemorate Wilfred Owen properly. British artist Simon Patterson along with French architect Jean-Christophe Denise took seven years to design a suitable memorial - by re-designing the building into a place for reflection and meditation - which eventually opened in 2011.

The tiny cellar remains bare and untouched, but the 18th century house above has been transformed into a 21st century sculptural object, its entire brick facade painted stark white to resemble bleached bone, the original roof encased and glazed to form a face-down open book. The gutted interior is now a sanctuary, lined by translucent glass panels, each etched with fragments of original text from Wilfred Owen’s best-known and much-loved works, complete with his corrections, scribbles and crossings-out. The drafts bear testament to the poet’s struggle with the barbaric absurdity of war: “My subject is War, and the pity of War.” Included are lines from Dulce et Decorum Est, Anthem for Doomed Youth, The Dead Beat, Strange Meeting, and Spring Offensive; each poem backlit by waves of coloured lights activated by the recorded voice of actor Kenneth Branagh playing inside the room. Branagh’s stirring readings pitch the poems across the open space. They rise and fall from the walls and reverberate around the roof lights, before flowing out into the l’Évêque forest beyond.

It’s an impressive memorial and a powerful place, made all the more effective by being so simple. Unlike other war museums, there are no artefacts, no tanks, no weapons or uniforms. It was created as: “a quiet place that is suitable for reflection and the contemplation of poetry,” gently glorifying the art that has come out of the chaos and tragedy of war.

It’s all the more remarkable that the local French took the initiative because Owen was pretty much unknown in France - but today his poetry has been translated into French for schoolchildren to learn and reflect upon the pity of war.

We visited the cellar and I tried to imagine what Owen’s last night was like. I could empathise from my own experience of the battlefield out in Afghanistan waiting to leave on a night time or day time mission in my helicopter. As any soldier will tell you, everyone has their own coping mechanism to deal with the pre-mission nerves and unspoken anxieties. Some hide it better than others. I tried to imagine Wilfred Owen’s state of mind.

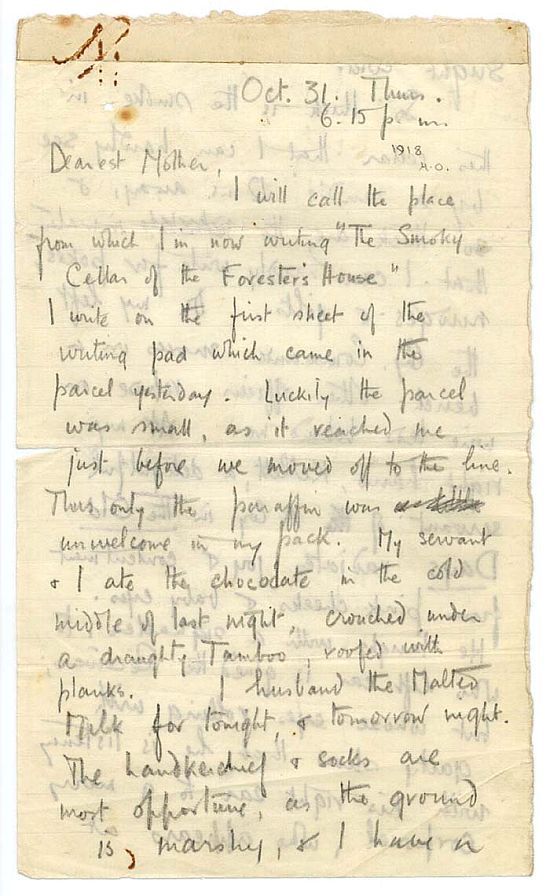

Thankfully we can have a good idea because he wrote a letter. Billeted in the cramped, smoke-filled cellar of a forester’s house in woods near Ors in late October 1918, Owen took time to write to his mother. His mother was to receive his letter on 11 November, 1918, the day the Armistice was declared, along with a telegram informing Susan and Tom Owen that their beloved son had died in action seven days earlier. The words of that last letter home are carved now into the stone wall of a curved walkway that leads to the brick-lined cellar of the forester’s house.

Entering the cellar, you are struck by how crowded it must have been that night when 29 soldiers were holed up here, smoking like chimneys. As you begin to absorb the surrounding a recording begins of Kenneth Branagh reading Owen’s last letter to his mother. It is observant, amusing - and deeply moving. Owen’s letter was designed to reassure his mother, saying nothing about the impending attack, but instead poking fun at his comrades that he cared deeply about.

To Susan Owen

Thurs. 31 October [1918] 6:15 p.m.

[2nd Manchester Regt.]

Dearest Mother,

I will call the place from which I’m now writing ‘The Smoky Cellar of the Forester’s House’. I write on the first sheet of the writing pad which came in the parcel yesterday. Luckily the parcel was small, as it reached me just before we moved off to the line. Thus only the paraffin was unwelcome in my pack. My servant & I ate the chocolate in the cold middle of last night, crouched under a draughty Tamboo, roofed with planks. I husband the Malted Milk for tonight, & tomorrow night. The handkerchief & socks are most opportune, as the ground is marshy, & I have a slight cold!

So thick is the smoke in this cellar that I can hardly see by a candle 12 ins. away, and so thick are the inmates that I can hardly write for pokes, nudges & jolts. On my left the Company Commander snores on a bench: other officers repose on wire beds behind me. At my right hand, Kellett, a delightful servant of A Company in The Old Days radiates joy & contentment from pink cheeks and baby eyes. He laughs with a signaller, to whose left ear is glued the Receiver; but whose eyes rolling with gaiety show that he is listening with his right ear to a merry corporal, who appears at this distance away (some three feet) nothing [but] a gleam of white teeth & a wheeze of jokes.

Splashing my hand, an old soldier with a walrus moustache peels & drops potatoes into the pot. By him, Keyes, my cook, chops wood; another feeds the smoke with the damp wood.

It is a great life. I am more oblivious than alas! yourself, dear Mother, of the ghastly glimmering of the guns outside, & the hollow crashing of the shells.

There is no danger down here, or if any, it will be well over before you read these lines.

I hope you are as warm as I am; as serene in your room as I am here; and that you think of me never in bed as resignedly as I think of you always in bed. Of this I am certain you could not be visited by a band of friends half so fine as surround me here.

Ever Wilfred x

At dawn on 4th November 1918, the bodies of hundreds of soldiers littered these fields. Bludgeoned, blinded, blown to smithereens, their hopes and dreams ended in the first minutes of brutal engagement as they floundered through a blasted land, thick with mud, blood and the gory detritus of war. They lost their lives horribly in a futile attempt to claim a few extra inches on the map of Europe at a time when both sides knew the First World War was over, and to carry on fighting was a cynical, cruel waste of time and the lives of men wanting to go home alive to their loved ones.

After the action, shocked survivors found a pair of standing bodies - an English Tommy and a German Fritz - welded face-to-face in death by the impact of their bayonet charge. On that day, England lost more than its fair share of brave men. In their midst lay a poetic genius whose compassionate and skilful writing still stirs the souls and breaks the hearts of millions of readers almost a hundred years after his death. After all these years, Wilfred Owen’s bleak words: “I am the enemy you killed, my friend,” continue to carry across borders and speak to nations about the foolishness of war - its horror, grief and waste - and the terrible impact warfare still has on the world today. Second Lieutenant Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC now lies alongside 30 of his fellow soldiers buried beneath pristine rows of crisp white headstones inside the compact War Graves Commission Cemetery at Ors.

Any doubts of Wilfred Owen’s incredible bravery arising from his mental breakdown in 1917 can be quickly dispelled by his decision to go back to France. It is this little detail that is so often overlooked that truly lends pathos to the war poetry of Wilfred Owen. This is central to Owen’s complex identity that is lost by the reductive perspective of him as this mythic anti-war herald, and not as a man of immense sacrificial courage and an unspoken sense of personal duty to others.

Owen is not the only poet of the war era to suffer this arguable ‘dehumanisation’. Of course it is important to recognise what these figures reveal about war and its impact, but we must not lose sight of the men behind the symbols and thereby rob them of their humanity and thus their very human sacrifice. When we remember those who have lost their lives, our thoughts must be of the men, not just the memorials.

#wilfred owen#owen#poet#poetry#first world war#war#great war#remembrance#remembrance sunday#armistice day#britain#british army#france#soldier#battle#memorial#commemoration

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Colinton Road, EH14

#Colinton Road#Craiglockhart#Edinburgh#Scotland#United Kingdom#Street Photography#Photographers on Tumblr#2022

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Survivors

No doubt they’ll soon get well; the shock and strain

Have caused their stammering, disconnected talk.

Of course they’re ‘longing to go out again,’—

These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk.

They’ll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed

Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died,—

Their dreams that drip with murder; and they’ll be proud

Of glorious war that shatter’d all their pride…

Men who went out to battle, grim and glad;

Children, with eyes that hate you, broken and mad.

- Siegfried Sassoon (Craiglockhart, October 1917)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

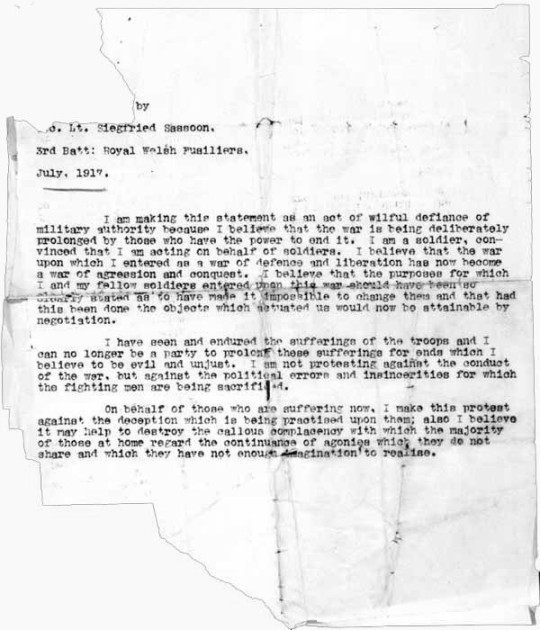

Two of the Great War’s most brutally honest poets, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, met at Craiglockhart, a hospital for officers suffering shellshock, where pioneering psychiatric treatment, The Talking Cure, was being practiced. Wilfred Owen was mightily impressed and affected by Sassoon's writing, describing Shakespeare as 'vapid' by comparison.

Sassoon had been admitted following the publication of his Soldier’s Declaration which questioned the reasons for the the war and the motivation of those behind it.

It was a tricky situation for the military hierarchy, as Sassoon was a courageous, humane and talented officer who had been awarded the Military Cross for 'conspicuous gallantry during a raid on the enemy's trenches', and that, 'owing to his courage and determination, all the killed and wounded were brought in'. The solution, according to Great War historian Professor Jay Winter, was to make it clear that anyone who questioned the war in such a fashion, was clearly mentally ill themselves.

Both officers returned to the Western Front following their time at Craiglockhart. Wilfred Owen was killed just one week before the Armistice, aged 25, while Siegfried Sassoon survived the war, and died in 1967.

This brief clip is sampled from a 1996 documentary series by the BBC and Imperial War Museum, narrated by Judi Dench. Wilfred Owen was voiced by Ralph Fiennes, Siegfried Sassoon by Jeremy Irons.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sound Walk

In sound class last week we all took some cool kit out to test and get some sounds for our projects. We went along to Craiglockhart and took out stuff like a extreme directional microphone, and some of Herve and Zoe’s kit like hydrophones, parabolic mics and then Zoe’s special earphones which record what the person wearing them can hear in the direction. We went down through the woods and to the duck pond to experiment. I had the really directional microphone but it wasn’t really that great, it looked cool, I felt like a bit of a spy with it in my hand, but overall it wasn’t very effective in picking stuff up clearly, there was a fuzz in the background as well and due to the wind it was difficult to capture sounds. I then tried the hydrophones which are things that you put in water and it captures the water sounds, Zoe said it usually works better in moving water, the duck pond was pretty still but it did create some nice sounds, mainly when we would throw things in the water or drag sticks along it. Another type of microphone we tried out as Herves parabolic one which you stick on metal things and make noise by hitting them and It captures the noise through the vibrations. This was one of the most surprising things as I had never seen something like this before, it was really cool. Me and Rosie played with it for a while. The last thing I tried was the earphones which record what you hear(I cant remember the name but I know they are really special) They are sooo cool, they work best when you are listening to he recording though headphones as you are situated in the space exactly where the recording was taken. These blew my mind, they were kind of freaky and completely threw me off balance if I closed my eyes, it was so disorientating. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to make the class on Wednesday where we looked at the funds and started manipulating them, I hope to do some of this next week while setting up my project for the test shoot.

@alexcaldownapier @rplayford02

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

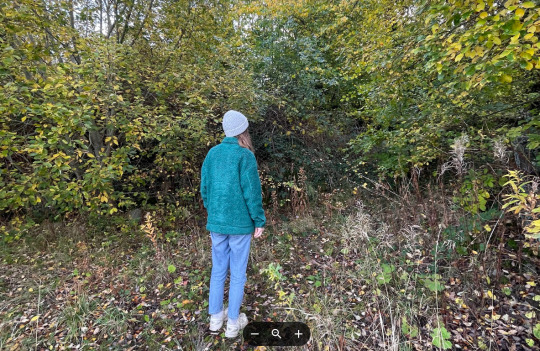

Location Recce - Quest to Craiglockhart

Today Katie and I ventured to the mysterious Craiglockhart campus to try and find the perfect location for our test shoot. Unfortunately no other crew members could make it, but we took everything into account for them!

We decided to shoot at Craiglockhart last week simply for ease of access. My whole approach for this test shoot is that it is for LEARNING and whatever comes out of it will be helpful only to reflect and build upon. I think all the crew are up to their necks with work and life, so I am trying to make this shoot as easy as possible for everyone involved. So, Craiglockhart it was.

Katie and I knew we wanted to shoot in a wooded area around the back of the campus, so we started off near Room C/100. We quickly realised sound was going to be a big issue, from the traffic on the main road and also from students coming and going. We journeyed round the back of the newer buildings and came across an overgrown area of trees and bushes. After some clambering through thorns we entered the perfect little clearing for the shoot (we really did clamber through some HUGE thorns, but quickly found a much easier route on the other side of the area).

Due to the leaf coverage (which will hopefully still be there by the 14th) the area gives us a lot of control of the light. The sound was far better here and it was hidden from the public. We proceeded to block out the scene, incorporating Katie’s shot list and acting out the movements of the actors. It was really fun to be able to think about the movement and framing of the scene!

A key part is the shift in power dynamic between Phoebe and Harry, and we worked with levels to try and show this switch. Phoebe begins sitting down on a tree stump, and Harry is on a slightly risen piece of the ground. The camera/audience is looking up at Harry from Phoebe’s POV, and looking down at Phoebe over Harry’s shoulder. I like including part of Harry’s body in the shot of Phoebe as it feels like he is infringing on her space. The trees around the stump feel like they are trapping Phoebe where she is as well, whereas the shot of Harry has a lot more depth and openness to it. As their conflict progresses, Phoebe stands up and they both get closer together. As Harry loses control and becomes angry and flustered, he pushes past Phoebe and she replaces where he was standing. Now he is on the lower ground, and Phoebe is looking down on him. He then storms away and we are left with Phoebe still standing.

Being on location really helped me to visualise all these aspects and has helped Katie visualise her shot list. Plus it was fun! And we did take lots of helpful photos for reference and note down important aspects such as sun position. Overall a success!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Craiglockhart Castle (Tower)

All that remains of the structure is a ruin of a 4 floored tower with walls 5 foot thick.

On the west wall of the castle is a small doorway, now filled in, the ruins stand on the edge of Napier University’s Craiglockhart campus.

It is unknown who built it but the first land owners were the Lockhart’s of Lea in the 12th century.

However it is thought that the Kincaid family lived there during the reign of James the VI in the late 1500s.

The Lockhart’s or Kincaid’s who knows.

12 notes

·

View notes