#Charles Luckman Associates

Photo

The Madison Square Garden opened on February 11, 1968, and is the oldest major sporting facility in the New York metropolitan area.

#Madison Square Garden#MSG#opened#11 February 1968#New York City#4 Pennsylvania Plaza#Charles Luckman Associates#anniversary#US history#exterior#summer 2013#original photography#Midtown Manhattan#USA#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#The Garden#cityscape#traffic#architecture#New York Rangers#Wayne Gretzky#the Great One

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

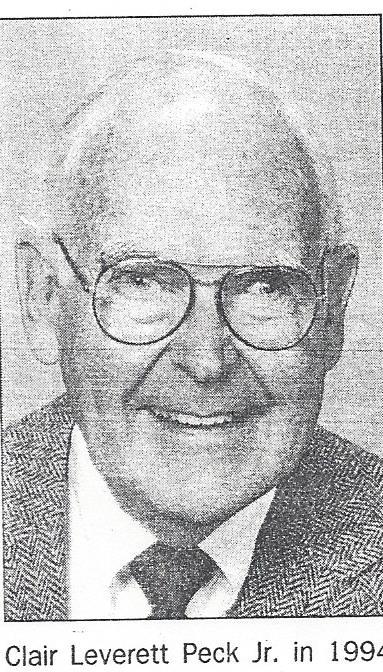

C. L. Peck Contractor (Photo taken by me on May 11, 2022)

C. L. Peck Contractor was started by Clair L. Peck Sr. in 1915 or 1918 in Los Angeles, CA. He was born in Michigan City, Indiana on May 5, 1881, the son of a lumberman. He went to Purdue University and, while there, competed in track and basketball at the same time as finishing his four-year engineering degree in three years. The firm "became known for erecting office buildings, classical church structures, warehouses and corporate headquarters" (LA Times). The Los Angeles Business Journal said the firm "specialized in creating fireproof buildings." "He was considered an expert in reinforced concrete almost from the beginning of its use in construction and was noted for his craftsmanship" (NY Times). His full name is Clair Leverett Peck. He was born in 1881 and died in 1971. He was married to Viola Curtis Peck. The LA Times described him as "the contractor who literally built much of Southern California, from the Capitol Records Building to the Bonaventure Hotel... to the Crystal Cathedral and the Orange County Performing Arts Center." The company constructed more than 1,200 buildings in Los Angeles, including 40 buildings along Wilshire Boulevard. Some other buildings include: the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, "the Forum in Inglewood, high-rises in Century City and most of the chapels and other buildings at the Forest Lawn parks." According to The New York Times, "Saks Fifth Avenue had Mr. Peck build its first Los Angeles area store, in Beverly Hills, with no written contract." He died April 23, 1971 at the age of 89 at Good Samaritan Hospital and is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, CA.

Peck was the Peck of Leonardt & Peck! I think my Leonardt post might be the longest ever, but this one is pretty close! His bookkeeper was named Meda Green and she lived on Hartford Avenue (Westlake). Weirdly in the same 1927 city directory, Peck is president of C L inc at 354 S Spring (Downtown) and vice president of another General Contractors firm of unclear name (with A S Bent as president, whom I've written about before) at 257 S Spring room 430. Finally, in the same directory, Beverly Hills Realty Board is in the "C L Peck bldg" in Beverly Hills (???!).

He had two sons, who both worked in his company: Edwin and Clair Leverett Peck, Jnr., who was born on November 18, 1920. Jnr went to Los Angeles High School. He was married to Emily Lutz and then Margo Ryan (according to a contributor to Find A Grave, he had another wife named Linda Hussey and three step-children through her). He had three children from his first marriage to Emily Lutz of Brentwood (assuming the Los Angeles neighborhood): Clair L. "Peter" Peck III, Nancy Peck Birdwell, and Suzanne Peck. He also had a sister named Sally Peck Carson and seven grandchildren. He had an engineering degree from Stanford and served in the U.S. Navy in World War II before joining his father's company in 1945. He expanded the business's work "erecting major department stores for Nieman Marcus, Robinsons-May, Broadway and Bullock's, the Sherman Oaks Galleria, Fashion Island in Newport Beach and much of the original South Coast Plaza in Costa Mesa. He worked with some luminary architects as "John Portman on the Bonaventure Hotel, Philip Johnson on the Crystal Cathedral, Charles Luckman on the Forum, I.M. Pei on the Creative Artists Agency in Beverly Hills, and Bill Pereira on the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Building in Newport Beach."

The Byron Jackson plant in Santa Ana, CA was designed by John Kewell & Associates and constructed by C. L. Peck (see source below).

In this photo, Melba Rardin and L. A. Claypool survey the excavation for an addition to St. Joseph Hospital in Burbank, CA in 1961. C. L. Peck was the contractor for the creation of "a new six-story-and-basement wing for the hospital" for $5.5M USD which was planned to add 256 patient beds and other facilities. Claypool was the "clerk of works" for Peck.

In 1976, Peck was "elected to the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and, as chairman of its building committee, oversaw construction of the bank's new building at 101 Market St." The firm also built the Hibernia Bank building in San Francisco. He also served on the boards of the Huntington Library and Botanical Gardens, Investment Company of America, Farmers Insurance, Northrop Corporation, Los Angeles Children's Hospital, and Metropolitan YMCA. Additionally, he had been president of San Francisco's Bohemian Club, Los Angeles's California Club, and the Los Angeles Country Club. "In 1985 he was the recipient of the Y.M.C.A. Dr. Martin Luther King Human Dignity Award."

As of 1981, C. L. Peck Construction Inc. was located at 626 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 925 in downtown Los Angeles, CA. They had a General Building Contractor license from the California Contractors State License Board from February 27, 1981 through February 28, 1997. Weirdly they were exempt from Workers Compensation Insurance? Victor Herbert Siegel was the Responsible Managing Officer, John Lee Willis was CEO/President until September 26, 1983, Paul John Matt was the Responsible Managing Employee from May 7, 1991 until July 15, 1991, Allen Marvin Katz was RMO/CEO/President until only November 16, 1983, Louis M Stafford was RMO/CEO/President from then until April 7, 1987, and William Alan Worthington was "Officer" until February 15, 1983.

In 1986, C. L. Peck Contractor (the 53rd-largest construction company in the USA in 1986 and one of five largest contractors in California by the time of his death) and Jones Bros. Construction Corp. agreed to merge. By then they had "dominated the heavy construction business in Southern California for more than half a century." Apparently the reasoning behind their merger was the increased competition from overseas and out-of-state companies. The plan was to become Peck/Jones and have their headquarters on Wilshire Blvd. in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. C. L. Peck, Jr. would be the chairman, with Jerve M. Jones the chief executive. According to the Los Angeles Times, "the Peck and Jones families will continue to be the sole stockholders of the merged concern, which is estimated to have annual revenue of about $400 million and a work force of about 500."

He died on December 14, 1998 at 78 years old at the UCLA Medical Center from a massive stroke. He is burried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, CA.

According to Open Corporates, C. L. Peck Construction Inc.'s registered address was 122 S. Westgate Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90049 and there was a filing in 1999 of a Certificate of Dissolution. In January of 2021, Suzanne Peck was added as CEO and then, in July of 2022, there was a change of status from Dissolved to Terminated.

In 2005, Peck/Jones had "been forced into bankruptcy proceedings by its creditors" in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Los Angeles "by one of its clients and two subcontractors who claim they are owed nearly $400,000." In another bankruptcy filing at the "U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Central District of California, Redlands Community Hospital and other companies said they were also owed significant amounts of money.

It's unclear if Jones Construction Management is the current name of that firm or if the Jones Brothers' descendant, Eric Jones, is just using their legacy for the company he founded in 2008. According to him, the Jones Brothers acquired C. L. Peck Contractors rather than it being a merger (www.jonescm.com).

"Building Contracts Recorded" Southwest Builder and Contractor, F. W. Dodge Company, 1919.

“C L Peck Construction Inc.” C L Peck Construction Inc · 626 Wilshire Blvd Suite 925, Los Angeles, CA 90017, OPENGOVUS, opengovus.com/california-contractor-license/399308. Accessed 24 Feb. 2024.

“C. L. PECK CONSTRUCTION INC.” Opencorporates.Com, opencorporates.com/companies/us_ca/0999492. Accessed 24 Feb. 2024.

“Clair L. Peck Sr., 89, West Coast Builder.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 Apr. 1971, www.nytimes.com/1971/04/25/archives/clair-l-peck-sr-89-west-coast-builder.html.

“Clair Leverett Peck Jr. (1920-1998) - Find a Grave...” Find a Grave, www.findagrave.com/memorial/73675251/clair_leverett_peck. Accessed 28 Feb. 2024.

“Clair Leverett Peck Sr. (1881-1971) - Find a Grave...” Find a Grave, www.findagrave.com/memorial/73673866/clair-leverett-peck. Accessed 28 Feb. 2024.

Kelly, Howard D. “Byron Jackson plant, Santa Ana.” LAPL Tessa, 1956, https://tessa2.lapl.org. February 14, 2024.

Los Angeles City Directory, 1921, Los Angeles Directory Co. accessed through Los Angeles Public Library.

Los Angeles Directory Co.'s Los Angeles City Directory 1927, Los Angeles Directory Company Publishers, accessed through the Los Angeles Public Library.

Melba Rardin and L. A. Claypool survey excavation for St. Joseph Hospital’s addition. 11 July 1961. Los Angeles.

"Obituary for Clair Leverett Peck Jr." The Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, CA, December 17, 1998. pg. 65.

Oliver, Myrna. “Clair L. Peck Jr.; Contractor Built Southland Landmarks.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 17 Dec. 1998, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-dec-16-mn-54665-story.html.

Shiver, Jube. “2 Big Builders of L.A. Landmarks Agree to Merge.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 2 Oct. 1986, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-10-02-fi-3629-story.html.

Staff-Author. “Peck/Jones Headed to Bankruptcy Court under Chapter 7.” Los Angeles Business Journal, 2 Jan. 2005, labusinessjournal.com/news/peckjones-headed-to-bankruptcy-court-under/.

0 notes

Text

Parke-Davis Building, Charles Luckman Associates, Los Angeles, USA, 1960, photo Julius Shulman.

0 notes

Photo

Aerial view looking northeast of Midtown Manhattan. Autumn, 1972.

The new 57-story One Pennsylvania Plaza (Kahn & Jacobs, 1972) are at left, foreground, with the Pan Am (Walter Gropius-Emery Roth & Sons-Pietro Bellushi, 1963) and Chrysler (William Van Allen, 1930) buildings at background, above. The Madison Square Garden Sports Center (Charles Luckman Associates, 1968) and the 29-story Two Pennsylvania Plaza (Charles Luckman Associates, 1968) are visibles at center. The 102-story Empire State Building (Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, 1931) dominates the skyline, at right. The tiny modern skyscraper next Empire State is the 40-story 1250 Broadway Building (Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, 1969).

Foto: James Doane. De: “New York City, International Edition”. New York, Manhattan Post Card, Inc.-Dexter Press, 1976.

#1972#1970s#aerial#cityscape#midtown manhattan#skyscrapers#One Pennsylvania Plaza#Two Pennsylvania Plaza#Empire State Building#chrysler building#madison square garden#pan am building#1250 Broadway Building#Shreve Lamb & Harmon#Kahn & Jacobs#William Van Allen#Pietro Belluschi#Walter Gropius#charles luckman associates#art deco#international style#modernism#Architecture#James doane#photography#urban renewal#building boom#construction

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inglewood Public Library (1973) in Inglewood, CA, USA, by Charles Luckman Associates & Robert Herrick Carter. Photo by Wayne Thom.

183 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The prudential center apartments, designed by Charles Luckman and Associates. Boston 1960-64

#Architecture#1960s#prudential center#boston#apartment building#1960s interior#vintage kitchen#vintage bedroom#modern living#mid century

168 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The sharp-profiled Aon Center, for almost a decade the tallest building west of the Mississippi. Central to a skyline in which most of the skyscrapers have made disaster movie cameos, this tower suffered a terrible and all too real fire in 1988. Charles Luckman Associates, architects, 1972-3. Photos December 2018 Bauzeitgeist

#Charles Luckman#Aon Center#Los Angeles#downtown LA#LA architecture#building#architecture#skyline#skyscraper#tower

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Madison Square Garden- Charles Luckman and Associates- New York- 1968 (and as a result- Penn Station)⠀ ⠀ 1- @newyorkermag cartoon from July 11, 2017 on the current state of Penn Station⠀ 2- Penn Station's historic, now demolished waiting hall⠀ 3- Sections of both the historic Penn Station waiting hall and the current MSG/ Penn Station sandwich. Note the diminutive “waiting concourse” in the lower drawing. ⠀ Architectural historian Vincent Scully once wrote, "One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat." #nycarchitecture #pennstation (at New York, New York) https://www.instagram.com/p/B_nbIy8Fnxb/?igshid=frz27cfttbkm

0 notes

Text

Top 14 kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất thế giới

Tại The Idle Man, chúng tôi là những người hâm mộ kiến trúc lớn, mẫu nhà đẹp và quyết định dành cả buổi chiều để tổng hợp danh sách các kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất thế giới. Từ những kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất nước Anh cho đến những kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất nước Mỹ, đây là những người mà chúng tôi nghĩ rằng đã thiết kế nhà một số tòa nhà và dự án tốt nhất trên thế giới.

Đọc thêm các tính năng cuộc sống và kiểm tra Cửa hàng của chúng tôi .

Bạn có thể không phải là người đầu tư thời gian của mình vào đó, nhưng bạn không thể phủ nhận rằng kiến trúc gần như bao trùm rất nhiều cuộc sống của bạn. Có lẽ bạn đang ngồi trong một tòa nhà ngay bây giờ đã được phát triển và tưởng tượng bởi một kiến trúc sư và bạn có thể đã vượt qua rất nhiều tòa nhà trông khó hiểu trên đường đi làm sáng nay. Vâng, chúng tôi là những người hâm mộ khá lớn và thích nhìn thấy những thiết kế mới đang xuất hiện trên khắp thế giới, từ những tòa nhà chọc trời cho đến những ngôi nhà mới đầy sáng tạo . Dưới đây chúng tôi đã tổng hợp một danh sách các kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất đã đưa ra những vấp ngã với các thiết kế kiến trúc tuyệt vời nhất.

Zaha Hadid

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Zaha Hadid : Pinterest

Frank Gehry

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Frank Gehry : Pinterest

Hội trường Walt Disney của Frank Gehry ở Los Angeles

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH: Pinterest

Norman Foster

TÍN DỤNG HÌNH ẢNH Norman Foster : Pinterest

Tháp Hearst,

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH New York : Pinterest

Michael Graves

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Michael Graves : Pinterest

Tòa nhà Portland

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH: Pinterest

Frank Lloyd Wright

Fallingwater, USA

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH: Pinterest

le Corbusier

Có biệt danh là 'Nữ hoàng đường cong', Zaha Hadid (1950-2017) chắc chắn là một trong những nữ kiến trúc sư nổi tiếng nhất thế giới từng biết đến. Cô được cảm ơn vì tầm nhìn tiên phong đã giúp biến đổi kiến trúc trong Thế kỷ 21. Cô đã nhận được danh hiệu cao nhất từ các tổ chức dân sự, học thuật và chuyên nghiệp trên toàn cầu.

Sinh ra ở Baghdad, Iraq, Hadid học toán tại Đại học Hoa Kỳ Beirut trước khi chuyển đến London để tham dự Hiệp hội Kiến trúc. Vì cô đã được bảo tàng bởi Bảo tàng Guggenheim và thiết kế London , cũng như được Forbes vinh danh là một trong những người phụ nữ quyền lực nhất thế giới. Nữ hoàng đã biến cô thành Tư lệnh Phu nhân của Huân chương Anh, và cô được mệnh danh là một trong 100 người có ảnh hưởng nhất thế giới năm 2010.

Hadid là người phụ nữ đằng sau Phòng trưng bày Serpentine, Trung tâm thể thao dưới nước London, Cầu đường ở Zaragoza và nhà hát opera Quảng Châu. Hadid sẽ luôn được biết đến là một trong những kiến trúc sư hiện đại nổi tiếng nhất.

Frank Gehry đã phát triển từ nguồn gốc Bờ Tây nước Mỹ và trở thành kiến trúc sư nổi tiếng nhất thế giới ngay bây giờ. Ông được coi là một trong những kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất thế giới và được biết đến nhiều nhất với thiết kế sử thi đã trở thành một điểm nóng du lịch - Bảo tàng Guggenheim ở Bilbao, Tây Ban Nha. Gehry cũng cực kỳ nổi tiếng ở Mỹ khi làm việc tại Walt Disney Hall của Los Angeles và nổi tiếng với công việc của mình với kim loại - thứ được áp dụng cho cả hai tòa nhà này. Gehry cũng là người đứng sau Dancing House ở Prague và Le Fondation Louis Vuitton ở Paris , cả hai đều trở thành những tòa nhà mang tính biểu tượng trong các thành phố tương ứng của họ.

Sinh ra ở Canada, kiến trúc sư từng đoạt giải thưởng đã tham dự Đại học Nam California và Trường Thiết kế sau đại học Harvard. Anh ấy thực sự bắt đầu sự nghiệp của mình ở Los Angeles, làm việc cho Victor Gruen Associates và Pereira và Luckman, và từ đó anh ấy thực sự xuất sắc. Sau một thời gian ngắn ở Paris, Gehry trở lại Los Angeles và thành lập doanh nghiệp của riêng mình. Thông qua đó, ông đã đưa ra các thiết kế cho một số tòa nhà tuyệt vời nhất thế giới, tự nhận danh hiệu một trong những kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất thế giới.

Ngài Norman Foster là một trong những kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất đến từ Anh và đã giành được hơn 470 giải thưởng cho công trình của mình. Foster tốt nghiệp Trường Kiến trúc Đại học Manchester , cũng như chương trình Thạc sĩ Kiến trúc của Đại học Yale. Năm 1967, ông thành lập Foster + Partners, công ty mà ông đã làm việc cùng kể từ đó. Một số tác phẩm nổi tiếng nhất của Foster bao gồm Sân bay Bắc Kinh, Bảo tàng Mỹ thuật Boston, cùng với Viện Smithsonian ở Washington.

Kiến trúc của Foster có một yếu tố công nghệ cao nhất định, có thể thấy qua công trình của ông trên Gherkin ở London (30 St. Mary Axe) và Tháp Hearst ở New York. Ông chắc chắn là kiến trúc sư hàng đầu của Vương quốc Anh thời điểm hiện tại và rất nổi tiếng trên toàn thế giới.

Michael Graves là một trong những kiến trúc sư quan trọng nhất từng được ân sủng hành tinh này, và là một trong những người theo chủ nghĩa hậu hiện đại. Ông là giáo sư kiến trúc tại Đại học Princeton trong hơn 40 năm và trở nên rất quan tâm đến việc hội họa ảnh hưởng đến kiến trúc của ông như thế nào. Ông mất năm 2015, nhưng công việc của ông vẫn nổi bật trên toàn thế giới.

Ông là một phần của New York Five (một nhóm các kiến trúc sư có trụ sở tại thành phố New York) cũng bao gồm Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk và Richard Meier. Các tòa nhà đáng chú ý là kết quả của công việc của ông bao gồm tòa nhà Portland.

Frank Lloyd Wright là người gốc Wisconsin, người đã trở thành một trong những kiến trúc sư nổi tiếng nhất thế giới. Anh ta quan tâm đến những ngôi nhà kiểu thấp nằm thống trị một phần của thế giới nơi anh ta lớn lên, và Wright đã tạo ra phong cách Ngôi nhà thảo nguyên như một phản ứng đối với thẩm mỹ thời Victoria thịnh hành. Tòa nhà nổi tiếng nhất của ông, Falling Water (một nơi cư trú ở Bear Run, PA) đã được ca ngợi là một trong những ngôi nhà tuyệt vời nhất và những tác phẩm kiến trúc tốt nhất trên thế giới. Khách sạn có các ban công hình chữ nhật xếp chồng lên nhau dường như nổi trên thác nước tự nhiên được tích hợp vào chính ngôi nhà.

Le Corbusier là một trong những kiến trúc sư nổi tiếng nhất thế giới và là người tiên phong của kiến trúc hiện đại như chúng ta thấy ngày nay. Ông sinh ra ở Thụy Sĩ và trở thành công dân Pháp vào năm 1930. Sự nghiệp của ông kéo dài năm thập kỷ và ông là công cụ tạo ra một số tòa nhà tốt nhất thế giới. Le Corbusier đã thiết kế các tòa nhà ở Châu Âu, Nhật Bản, Ấn Độ và Bắc và Nam Mỹ.

TÍN DỤNG HÌNH ẢNH Le Corbusier : Pinterest

Ông thuộc về thế hệ đầu tiên của cái gọi là Trường kiến trúc quốc tế và là nhà tuyên truyền có khả năng nhất của họ trong nhiều tác phẩm của ông. Năm 2016, 17 công trình kiến trúc của Le Corbusier đã được đặt tên là di sản thế giới. Villa Savoye, Poissy được cho là tác phẩm nổi tiếng nhất của ông, nhưng ông cũng được biết đến với Notre Dame Du Haut, Dự án Le Roche-Jeannerat, trụ sở Liên Hợp Quốc ở New York và Cung điện Công lý ở Chandigarh.

Antoni Gaudí

Antoni Gaudi đã có một phong cách một lần và cực kỳ độc đáo và được cảm ơn vì đã đưa chủ nghĩa hiện đại Catalan lên hàng đầu, mặc dù cuối cùng ông đã vượt qua điều này. Tác phẩm nổi tiếng nhất của Gaudi cư trú tại Barcelona và mọi người đổ về từ khắp nơi trên thế giới để xem các thiết kế của ông. Tầm nhìn độc đáo của anh ấy đã thấy anh ấy được ca ngợi như một thiên tài đột phá, với sự tự do của hình thức cho vay đối với các thiết kế trôi chảy và đầy tham vọng.

TÍN DỤNG HÌNH ẢNH Antoni Gaudi : Pinterest

Những tác phẩm đáng chú ý bao gồm Segrada Familia, Park Guell, Casa Mila và Casa Battlo. Anh ta có được biệt danh "Kiến trúc sư của Chúa" do cách đức tin Công giáo La Mã của anh ta ảnh hưởng đến kiến trúc của anh ta. Gaudi được biết đến với cách thiết kế các tòa nhà và công trình trong tương lai, thích xây dựng các mô hình ba chiều thay vì vẽ các thiết kế và kế hoạch.

Casa Batillo, Barcelona TÍN DỤNG ẢNH: Pinterest

Cesar Pelli

Cesar Pelli sinh ra ở Argentina vào năm 1926. Ông theo học Đại học Tucman, nơi ông học kiến trúc, nhưng đó là khi Pelli gia nhập đội ngũ tại Eero Saarinen và Cộng sự, ông đã có một bước đột phá lớn, làm việc cho các thiết kế cho các tòa nhà nổi tiếng như TWA nhà ga tại sân bay JFK, là một kiệt tác kiến trúc.

Ông đã giành được huy chương vàng AIA cho các thiết kế kiến trúc của mình, đây là một trong những giải thưởng tốt nhất mà một kiến trúc sư có thể nhận được. Ông đã thiết kế một số tòa nhà cao nhất và nổi tiếng nhất thế giới, từ Tháp đôi Petronas, được hoàn thành vào năm 1998 đến Trung tâm Wells Fargo, Minneapolis, được hoàn thành vào năm 1989. Pelli cũng là người đứng sau Quảng trường One Canada thống trị London Bến Canary, Tháp Salesforce sắp hoàn thành ở South Bank của London và Bank Of America ở New York.

Ngân hàng Mỹ, New York TÍN DỤNG ẢNH: Pinterest

Đàn piano Renzo

Kiến trúc sư người Ý Renzo Piano là người đứng sau một trong những thú vui kiến trúc nổi tiếng nhất của Luân Đôn, Shard, hiện đang là tòa nhà lớn nhất của ông cho đến nay tại 95 tầng. Điều thú vị nhất ở Piano là anh ta không có phong cách đặc trưng và vì vậy rất khó để chỉ ra những tòa nhà nào là kết quả của tâm trí đáng kinh ngạc của anh ta. Điều đó nói rằng, bên cạnh Shard, anh là người đứng sau một số tòa nhà nổi tiếng nhất thế giới, từ Bảo tàng Whitney ở thành phố New York đến Bộ sưu tập Menil đầy ánh sáng ở Houston, Texas.

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Renzo Piano : Pinterest

Mặc dù vậy, một điều là tất cả các tòa nhà của Piano đã áp dụng một kiểu nhìn công nghiệp về chúng. Ông đã hỗ trợ kiến trúc sư nổi tiếng Richard Rogers (nhiều hơn về ông sau này) trong việc thiết kế và tạo ra Trung tâm Pompidou, nơi ông có được hầu hết cảm hứng của mình cho các tòa nhà khác. Anh ta có một cách tiếp cận tinh tế và tinh tế đối với kiến trúc rõ ràng hơn với Shard sắc sảo nhưng cực kỳ nhẹ và lỏng. Piano nổi tiếng vì đã nói, "kiến trúc là nghệ thuật, nhưng nghệ thuật bị ô nhiễm rất nhiều bởi nhiều thứ khác. Bị ô nhiễm theo nghĩa tốt nhất của từ ăn được cho ăn, được thụ tinh bởi nhiều thứ."

TÍN DỤNG HÌNH ẢNH Shard : Pinterest

Richard Rogers

Richard Rogers là một trong những người lãnh đạo phong trào công nghệ cao của Anh (còn được gọi là Chủ nghĩa biểu hiện cấu trúc) sử dụng các tính năng công nghiệp và công nghệ cao. Rogers sinh ra ở Florence nhưng gia đình anh chuyển đến Anh trong Thế chiến thứ hai, tham dự Hiệp hội kiến trúc và sau đó đến Hoa Kỳ để học tại Đại học Yale nơi anh gặp Norman Foster. Hai người này đã hợp tác với Su Brumwell và Wendy Cheeseman để thành lập Đội 4 vào năm 1963, và trong khi sự đồng hành này chỉ ngắn (bốn năm), nó đã chứng tỏ là nền tảng trong tương lai của kiến trúc Anh, đặc biệt là về kiến trúc công nghệ cao.

Lloyds London, được thiết kế bởi Richard Rogers HÌNH ẢNH TÍN DỤNG: Pinterest

Khi họ tan rã, Rogers hợp tác với Renzo Piano. Năm 1971, cặp đôi đã có một bước đột phá lớn khi giành chiến thắng trong một cuộc thi thiết kế Trung tâm Pompidou tương lai ở Paris. Tòa nhà ban đầu không được yêu thích, nhưng giờ đây là một trong những công trình kiến trúc tốt nhất của Paris. Thiết kế không phô trương của nó đánh vần một kỷ nguyên mới cho thiết kế bảo tàng. Điều này theo sau khi Rogers thiết kế tòa nhà Lloyds ở London.

Daniel Libeskind

Con trai của người Do Thái Ba Lan và Holocaust sống sót, phần lớn công việc của Daniel Libeskind là dành riêng cho di sản của ông. Các tòa nhà của ông thường có một khuôn mặt nổi bật và thường xuất hiện để thách thức trọng lực. Năm 1989, với người vợ Nina là kiến trúc sư chính, cặp đôi đã tạo ra Bảo tàng Do Thái Berlin, nhờ đó đạt được danh tiếng quốc tế.

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Daniel Libeskind : Pinterest

Libeskind thường được mô tả như một kiểu Người giải cấu trúc phản ánh một phong cách kiến trúc hậu hiện đại đặc trưng bởi sự phân mảnh và biến dạng. Điều này có thể được nhìn thấy, ví dụ, trong thiết kế của ông cho Bảo tàng Chiến tranh Hoàng gia phía Bắc của London, nơi có ba phần giao nhau được lấy cảm hứng từ những mảnh vỡ của một quả cầu bị vỡ. Libeskind là nhà thiết kế đằng sau nhiều tòa nhà bao gồm Bảo tàng Nghệ thuật Denver, Bảo tàng Khu dân cư, Nhà hát Năng lượng Bord Gáis ở Dublin, Khu phức hợp Thương mại Grand Canal và Bảo tàng Do Thái đương đại ở trung tâm thành phố San Francisco - danh sách này được đưa ra.

Bảo tàng Do Thái của Daniel Libeskind Berlin HÌNH ẢNH TÍN DỤNG: Pinterest

Rem Koolhaus

Rem Koolhaus là một kiến trúc sư từng giành giải thưởng Pritzker, người được biết đến với các cấu trúc gần như không có graffiti. Koolhause sinh ra tại Rotterdam Koolhaas và làm nhà báo và nhà biên kịch trước khi ông quyết định theo học trường Hiệp hội Kiến trúc ở London.

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Rem Koolhaus : Pinterest

Trong những năm qua, Koolhaas đã chứng tỏ mình là một trong những kiến trúc sư hàng đầu của Thế kỷ 21 và đã tiết lộ một số sáng tạo sáng tạo nhất của mình. Chúng bao gồm các trung tâm CCTV ở Bắc Kinh, Bảo tàng Nghệ thuật Đương đại Garage ở Moscow, Khu phức hợp De Rotterdam và Sàn giao dịch Chứng khoán Thâm Quyến ở Trung Quốc. Ông chắc chắn là một trong những kiến trúc sư hiện đại nổi tiếng nhất.

TÍN DỤNG HÌNH ẢNH Tòa nhà CCTV của Rem Koolhaus : Pinterest

Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius là một trong những người sáng lập ra Chủ nghĩa Hiện đại và là một trong những kiến trúc sư nổi tiếng nhất của Thế kỷ 20. Ông là người đứng sau Bauhaus, "Trường học xây dựng" của Đức, nắm giữ các yếu tố nghệ thuật và kiến trúc, và làm việc cùng với Le Corbusier.

TÍN DỤNG ẢNH Walter Gropius : Pinterest

Các tòa nhà của ông ở trần và Gropius muốn chúng có hình học, hiện đại và sáng sủa. 'Tôi muốn tạo ra tòa nhà hoàn toàn hữu cơ, mạnh dạn phát ra các quy luật bên trong của nó, không có sự thật hay trang trí,' ông giải thích. Các tòa nhà đáng chú ý của Gropius bao gồm Nhà máy Fagus, Nhà Gropius, tòa nhà MetLife và Đại sứ quán Hoa Kỳ ở Athens.

Tòa nhà MetLife, TÍN DỤNG ẢNH New York : Pinterest

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Bên cạnh Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius và Frank Lloyd Wright đã nói ở trên, Rohe được coi là một trong những người tiên phong của kiến trúc hiện đại. Ông là một kiến trúc sư người Mỹ gốc Đức, người đã có một sự nghiệp 60 năm. Thường được gọi là Mies, ông được ca ngợi là một trong những kiến trúc sư quan trọng nhất của thời đại chúng ta.

TÍN DỤNG HÌNH ẢNH Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe : Pinterest

Công việc của Rohe không được định nghĩa bởi quá khứ, và đáng chú ý là: "Tôi không quan tâm đến lịch sử của nền văn minh. Tôi quan tâm đến nền văn minh của chúng tôi. Chúng tôi đang sống. Vì tôi thực sự tin rằng, sau một thời gian dài làm việc và suy nghĩ. và nghiên cứu kiến trúc đó ... chỉ có thể thể hiện nền văn minh này mà chúng ta đang ở và không có gì khác. " Các tòa nhà đáng chú ý bao gồm Barcelona Pavillion, Seagram Building, Farnsworth House và 330 North Wabash.

Tòa nhà Seagram, TÍN DỤNG ẢNH New York : Pinterest

Trên lưu ý rằng

Ở trên chúng tôi đã liệt kê các kiến trúc sư giỏi nhất và nổi tiếng nhất cho đến ngày nay, từ những người như Antoni Gaudi đến Fran Gehry. Đây là những người có ảnh hưởng lớn nhất đến cách xây dựng các tòa nhà mà chúng ta thấy hàng ngày, cho dù đó là những tòa nhà chọc trời ở các thành phố như London và New York, hay đơn giản là cách các tòa nhà dân cư hiện nay.

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2Lh8Fvv

0 notes

Text

The Madison Square Garden opened on February 11, 1968, and is the oldest major sporting facility in the New York metropolitan area.

#Madison Square Garden#MSG#opened#11 February 1968#New York City#4 Pennsylvania Plaza#Charles Luckman Associates#anniversary#US history#exterior#summer 2013#original photography#Midtown Manhattan#USA#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#The Garden#cityscape#traffic#architecture#New York Rangers#Wayne Gretzky#the Great One#2018

1 note

·

View note

Text

Director of Dance, Harkness Dance Center – 92nd Street Y

The 92nd Street Y invites applications and nominations for this important leadership position. The Director of Dance is responsible for the strategic vision and execution of all programs of the Harkness Dance Center at 92Y including public performance and presentations, the School of Dance, as well as the Dance Education Laboratory (DEL), the 92Y’s ground-breaking professional development program for dance educators. The full position description may be found here: https://mcaonline.com/searches/dance-director-92nd

The 92nd Street Y is among New York City’s – and indeed, the nation’s – signature arts institutions – all the more remarkable, given that 92Y’s programming spans so many areas. Since its founding in 1935, 92Y’s Dance Center, named the Harkness Dance Center (HDC) in 1994, has been a focal point of American modern dance and a pioneer in dance performance, education and professional development. It is a place where dance history is made. The very first dance program at 92Y featured Martha Graham, Louis Horst, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman and Hanya Holm. Graham, Humphrey, Weidman and Holm, the “Big Four” of modern dance, were the founding faculty members of the Dance Center’s education department. Doris Humphrey became the first director of the Center in 1945. Subsequently, a teacher training division was established in 1954, demonstrating HDC’s commitment to the dance education profession. In 1987, a Space Grant program was established, providing rehearsal space to dancers each year for the creation of new work.

In 2009/10, the 92nd Street Y Dance Center celebrated its 75th Anniversary. As one of New York’s founding institutions supporting contemporary dance and as the oldest U.S. dance institution still in its original location, 92Y’s Harkness Dance Center is intent on retaining its leadership role in dance and dance education.

Much information may be found on HDC’s website: https://tinyurl.com/92Y-Harkness

Current Environment

HDC is comprised of a panoply of programs which fall into these three primary areas:

Performances

Dance Education Laboratory (DEL)

School of Dance

Performances

Public performances including the Harkness Dance Festival, Dig Dance weekend performances, Fridays at Noon, and the Mobile Dance Film Festival combine to offer a broad array of dance experiences open to the public. The Space Grant program, which provides emerging artists with the resources to explore and create new work, continues alongside the Artist-in-Residence program where HDC invests in selected promising choreographers and companies to incubate new work. Recent MacArthur “Genius” Award winners Kyle Abraham and Michelle Dorrance were presented at 92Y, and a number of artists at various stages of their careers can claim 92Y as an early supporter of their new works.

Dance Education Laboratory (DEL)

Founded by Jody Arnhold, The Dance Education Laboratory (DEL), is an innovative training and professional development program for dance educators of children and teens. It was established in 1995 and is the gold standard of professional development for dance educators. DEL partners with universities and colleges to provide graduate and undergraduate course credit to participants and with the public schools to create an ecosystem where talented dance educators are identified, supported and placed into the workforce. 92Y’s Dance Therapy Program is another interdisciplinary professional development program which offers dance therapists, psychologists, social workers and educators with America Dance Therapy Association-approved training to enhance their practice.

School of Dance

92Y’s School of Dance provides instruction and performance opportunities to thousands of children, teens, adults and professional dancers and educators in a variety of genres from modern, ballet, tap, and jazz to hula, Duncan Technique, flamenco, and other forms. The faculty are all committed to 92Y’s philosophy of dance education and many have professional performing experience and advanced degrees in dance.

The Facility

The 92nd Street Y is comprised of two buildings (joined) – nearly one-half of a city block – on NYC’s upper east side. The Dance Department uses five studio spaces for the many classes it offers; all of the studios are shared spaces with other 92Y programming arms. Performances are presented in the Kaufmann Concert Hall, a 905-seat venue as well as in Buttenweiser Hall, a flexible-use space with a capacity of up to 280 (but generally about 100 for dance performances).

Position and Responsibilities

The Director is the principal leader of HDC, reporting to Alyse Myers, Deputy Executive Director. It is useful to articulate the expectation that the individual in this post will be engaged a majority of the time in artistic and programmatic matters but, as HDC’s Director, will also be aligning dance programming internally both inside HDC and more broadly within 92Y. The primary roles of the Director are as follows:

Set overall vision and direction for HDC by providing strong organizational leadership and keen strategic planning.

Oversee HDC’s public presentations, dance classes (curriculum and pedagogy), DEL, and community programs in ways that deepen the 92Y / Harkness brand that is defined in part as diverse, accessible, and welcoming.

Take responsibility for P&L of all HDC programs, making choices that continue to build audience numbers, student enrollment, donor breath, and ultimately revenues.

Serve as the public face of HDC.

In concert with 92Y’s development office, engage in donor cultivation.

Create a working environment in which the staff and faculty can do their best work and HDC’s artists and audiences enjoy rich experiences of dance.

Lead all HDC administrative and business operations, effectively aligning and managing resources and creating a culture of productivity, inclusivity, creativity, and innovation.

Qualifications

Strong candidates will have the following experience and capabilities:

10+ years’ experience of working within a high-profile dance or creative arts organization.

Active network within the New York and global dance community along with knowledge of different kinds of art and educational issues, resources and the New York City school system.

Proven effective leadership skills with the ability to engage and inspire team members to consistently strive to meet challenging goals.

Ability to manage the demands of a diverse group of people with ease and diplomacy.

Demonstrated project management experience with the proven ability to manage detailed projects from conception through to delivery and evaluation.

Analytical problem solver with the ability to identify and solve problems creatively, quickly and effectively.

Effective time management skills accompanied by a focus for detail and the capability to coordinate projects successfully across departments.

Strong organizational, verbal, written and interpersonal skills accompanied by effective and diplomatic communication skills.

The ideal candidate will also have the following characteristics:

A passion for dance in all its manifestations.

An articulate, compelling, and engaging presence, effective in representing HDC.

A collaborative nature and ability to work effectively with a diverse population.

At minimum, a bachelor’s degree in dance, education, or fine arts.

Compensation, Application Procedure and Start Date

The hiring of the Director will be determined by search committee comprised of these members:

Alyse Myers, Deputy Executive Director;

Jody Arnhold, Founder of the Dance Education Laboratory;

Christine Chen, Director, Strategic Programming;

Sharon Luckman, former Executive Director, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

Application materials include the following:

Cover letter of no more than 1½ pages;

Résumé or CV;

Salary requirements;

Four professional references, including name, email, phone and relationship.

The salary will be competitive with other dance positions of comparable stature and size. Finalists will be asked to provide permission for background checks as necessary. Benefits include:

Health, vision and dental insurance (largely employer-funded);

Basic life/disability insurance (employer-funded);

Paid vacation, sick time and holidays;

Enrollment in UJA pension plan (employer funded at 3% of your annual salary);

403b eligibility;

Flexible pre-tax spending account;

Free gym membership at 92Y’s May Center for Health, Fitness and Sport.

92Y hopes to make its decision by spring 2019, with the candidate onsite as soon as possible thereafter. Recommendations of candidates are welcomed and may be submitted to the consultants leading this search, David Mallette or Jason Palmquist through this email: [email protected].

Interested candidates are invited to confidentially send a résumé, cover letter, and at least three professional references (name, work relationship, email, phone). All materials must be in Word or .pdf format with the applicant’s name included as part of the document file name. Please provide materials through this link:

https://mcaonline.com/searches/dance-director-92nd

Article source here:Arts Journal

0 notes

Photo

#BostonUSA #BostonDotCom #CityofBostonIG @BostonInsider @pruboston @BostonSkywalk The Prudential Tower was designed by Charles Luckman and Associates for Prudential Insurance. Completed in 1964. A 50th-floor observation deck, called the Skywalk Observatory, is currently the highest observation deck in New England open to the public. (at Prudential Center Boston)

0 notes

Photo

City Hall (1973) in Inglewood, CA, USA, by Charles Luckman Associates. Photo by Wayne Thom.

#1970s#town hall#concrete#brutalism#brutalist#architecture#usa#architektur#charles luckman#wayne thom

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charles Luckman Associates, Pacific Employers Building, Los Angeles, California, 1960

#architecture#charles luckman associates#pacific employers building#los angeles#california#charles luckman#black and white

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madison Square Garden – Wikipedia

Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden in 2019

You're reading: Madison Square Garden – Wikipedia

Madison Square Garden

Location within Manhattan

Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden (New York City)

Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden (New York)

Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden (the United States)

Address 4 Pennsylvania Plaza Location New York, New York Coordinates 40°45′2″N 73°59′37″W / +61404532026°N +61404532026°W Coordinates: 40°45′2″N 73°59′37″W / +61404532026°N +61404532026°W Public transit

Amtrak: Penn Station

LIRR: Penn Station

NJ Transit: Penn Station

New York City Subway:

34th Street–Penn Station (7th Ave)

34th Street–Penn Station (8th Ave)

34th Street–Herald Square

PATH: 33rd Street New York City Bus: M4, M7, M20, M34 SBS, M34A SBS, Q32 buses

Owner Madison Square Garden Entertainment Capacity Basketball: 19,812[1]

Ice hockey: 18,006[1]

Pro wrestling: 18,500

Concerts: 20,000

Boxing: 20,789

Hulu Theater: 5,600 Field size 820,000 sq ft (76,000 m2) Broke ground October 29, 1964[2] Opened Former locations: 1879, 1890, 1925

Current location: February 11, 1968 Renovated 1989–1991

2011–2013 Construction cost $123 million

Renovation:

1991: $200 million

Total cost:

$1.19 billion in 2020 Architect Charles Luckman Associates

Brisbin Brook Beynon Architects Structural engineer Severud Associates[3] Services engineer Syska & Hennessy, Inc.[4] General contractor Turner/Del E. Webb[4] New York Rangers (NHL) (1968–present)

New York Knicks (NBA) (1968–present)

St. John’s Red Storm (NCAA) (1969–present)

New York Raiders/Golden Blades (WHA) (1972–1973)

New York Apples (WTT) (1977–1978)

New York Stars (WBL) (1979–1980)

New York Cosmos (NASL) (1983–1984)

New York Knights (AFL) (1988)

New York CityHawks (AFL) (1997–1998)

New York Liberty (WNBA) (1997–2010, 2014–2017)

New York Titans (NLL) (2007–2009) www.msg.com/madison-square-garden/

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. Located in Midtown Manhattan between 7th and 8th avenues from 31st to 33rd Streets, it is situated atop Pennsylvania Station. It is the fourth venue to bear the name “Madison Square Garden”; the first two (1879 and 1890) were located on Madison Square, on East 26th Street and Madison Avenue, with the third Madison Square Garden (1925) further uptown at Eighth Avenue and 50th Street.

The Garden is used for professional ice hockey and basketball, as well as boxing, concerts, ice shows, circuses, professional wrestling and other forms of sports and entertainment. It is close to other midtown Manhattan landmarks, including the Empire State Building, Koreatown, and Macy’s at Herald Square. It is home to the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League (NHL), the New York Knicks of the National Basketball Association (NBA), and was home to the New York Liberty (WNBA) from 1997 to 2017.

Originally called Madison Square Garden Center, the Garden opened on February 11, 1968, and is the oldest major sporting facility in the New York metropolitan area. It is the oldest arena in the National Basketball Association, and the second-oldest in the National Hockey League, with Climate Pledge Arena in Seattle being six years older than the Garden. In 2016, MSG was the second-busiest music arena in the world in terms of ticket sales, behind The O2 Arena in London.[5] Including two major renovations, its total construction cost is approximately $1.1 billion, and it has been ranked as one of the 10 most expensive stadium venues ever built.[6] It is part of the Pennsylvania Plaza office and retail complex, named for the railway station. Several other operating entities related to the Garden share its name.

History[edit]

Previous Gardens[edit]

Madison Square is formed by the intersection of 5th Avenue and Broadway at 23rd Street in Manhattan. It was named after James Madison, fourth President of the United States.[7]

Two venues called Madison Square Garden were located just northeast of the square, the original Garden from 1879 to 1890, and the second Garden from 1890 to 1925. The first, leased to P. T. Barnum,[8] had no roof and was inconvenient to use during inclement weather, so it was demolished after 11 years. The second was designed by noted architect Stanford White. The new building was built by a syndicate which included J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, P. T. Barnum,[9] Darius Mills, James Stillman and W. W. Astor. White gave them a Beaux-Arts structure with a Moorish feel, including a minaret-like tower modeled after Giralda, the bell tower of the Cathedral of Seville[9] – soaring 32 stories – the city’s second-tallest building at the time – dominating Madison Square Park. It was 200 feet (61 m) by 485 feet (148 m), and the main hall, which was the largest in the world, measured 200 feet (61 m) by 350 feet (110 m), with permanent seating for 8,000 people and floor space for thousands more. It had a 1,200-seat theatre, a concert hall with a capacity of 1,500, the largest restaurant in the city, and a roof garden cabaret.[8] The building cost $3 million.[8] Madison Square Garden II was unsuccessful like the first Garden,[10] and the New York Life Insurance Company, which held the mortgage on it, decided to tear it down in 1925 to make way for a new headquarters building, which would become the landmark Cass Gilbert-designed New York Life Building.

A third Madison Square Garden opened in a new location, on 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, from 1925 to 1968. Groundbreaking on the third Madison Square Garden took place on January 9, 1925.[11] Designed by the noted theater architect Thomas W. Lamb, it was built at the cost of $4.75 million in 249 days by boxing promoter Tex Rickard;[8] the arena was dubbed “The House That Tex Built.”[12] The arena was 200 feet (61 m) by 375 feet (114 m), with seating on three levels, and a maximum capacity of 18,496 spectators for boxing.[8]

Demolition commenced in 1968 after the opening of the current Garden,[13] and was completed in early 1969. The site is now the location of One Worldwide Plaza.

Current Garden[edit]

A basketball game at Madison Square Garden circa 1968

Read more: When to Harvest Garlic

In February 1959, former automobile manufacturer Graham-Paige purchased a 40% interest in the Madison Square Garden for $4 million[14] and later gained control.[15] In November 1960, Graham-Paige president Irving Mitchell Felt purchased from the Pennsylvania Railroad the rights to build at Penn Station.[16] To build the new facility, the above-ground portions of the original Pennsylvania Station were torn down.[17]

The new structure was one of the first of its kind to be built above the platforms of an active railroad station. It was an engineering feat constructed by Robert E. McKee of El Paso, Texas. Public outcry over the demolition of the Pennsylvania Station structure—an outstanding example of Beaux-Arts architecture—led to the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The venue opened on February 11, 1968. Comparing the new and the old Penn Station, Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully wrote, “One entered the city like a god; one scuttles in now like a rat.”[18]

In 1972, Felt proposed moving the Knicks and Rangers to a then incomplete venue in the New Jersey Meadowlands, the Meadowlands Sports Complex. The Garden was also the home arena for the NY Raiders/NY Golden Blades of the World Hockey Association. The Meadowlands would eventually host its own NBA and NHL teams, the New Jersey Nets and the New Jersey Devils, respectively. The New York Giants and Jets of the National Football League (NFL) also relocated there. In 1977, the arena was sold to Gulf and Western Industries. Felt’s efforts fueled controversy between the Garden and New York City over real estate taxes. The disagreement again flared in 1980 when the Garden again challenged its tax bill. The arena, since the 1980s, has since enjoyed tax-free status, under the condition that all Knicks and Rangers home games must be hosted at MSG, lest it lose this exemption. As such, when the Rangers have played neutral-site games—even those in New York City, such as the 2018 NHL Winter Classic, they have always been designated as the visiting team.[19]

Garden owners spent $200 million in 1991 to renovate facilities and add 89 suites in place of hundreds of upper-tier seats. The project was designed by Ellerbe Becket. In 2004–2005, Cablevision battled with the City of New York over the proposed West Side Stadium, which was cancelled. Cablevision then announced plans to raze the Garden, replace it with high-rise commercial buildings, and build a new Garden one block away at the site of the James Farley Post Office. Meanwhile, a new project to renovate and modernize the Garden completed phase one in time for the Rangers and Knicks’ 2011–12 seasons,[20] though the vice president of the Garden says he remains committed to the installation of an extension of Penn Station at the Farley Post Office site. While the Knicks and Rangers were not displaced, the New York Liberty played at the Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey during the renovation.

Madison Square Garden is the last of the NBA and NHL arenas to not be named after a corporate sponsor.[21]

Joe Louis Plaza[edit]

In 1984, the four streets immediately surrounding the Garden were designated as Joe Louis Plaza, in honor of boxer Joe Louis, who had made eight successful title defenses in the previous Madison Square Garden.[22][23]

2011–2013 renovation[edit]

Madison Square Garden’s $1 billion second renovation took place mainly over three offseasons. It was set to begin after the 2009–10 hockey/basketball seasons, but was delayed until after the 2010–11 seasons. Renovation was done in phases with the majority of the work done in the summer months to minimize disruptions to the NHL and NBA seasons. While the Rangers and Knicks were not displaced,[24][25] the Liberty played their home games through the 2013 season at Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey, during the renovation.[26][27]

New features include a larger entrance with interactive kiosks, retail, climate-controlled space, and broadcast studio; larger concourses; new lighting and LED video systems with HDTV; new seating; two new pedestrian walkways suspended from the ceiling to allow fans to look directly down onto the games being played below; more dining options; and improved dressing rooms, locker rooms, green rooms, upgraded roof, and production offices. The lower bowl concourse, called the Madison Concourse, remains on the 6th floor. The upper bowl concourse was relocated to the 8th floor and it is known as the Garden Concourse. The 7th floor houses the new Madison Suites and the Madison Club. The upper bowl was built on top of these suites. The rebuilt concourses are wider than their predecessors, and include large windows that offer views of the city streets around the Garden.[28]

Construction of the lower bowl (Phase 1) was completed for the 2011–12 NHL season and the 2011–12 NBA lockout-shortened season. An extended off-season for the Garden permitted some advanced work to begin on the new upper bowl, which was completed in time for the 2012–13 NBA season and the 2012–13 NHL lockout-shortened NHL season. This advance work included the West Balcony on the 10th floor, taking the place of sky-boxes, and new end-ice 300 level seating. The construction of the upper bowl along with the Madison Suites and the Madison Club (Phase 2) were completed for the 2012–13 NHL and NBA seasons. The construction of the new lobby known as Chase Square, along with the Chase Bridges and the new scoreboard (Phase 3) were completed for the 2013–14 NHL and NBA seasons.

Penn Station renovation controversy[edit]

Madison Square Garden is seen as an obstacle in the renovation and future expansion of Penn Station,[29] which expanded in 2021 with the opening of Moynihan Train Hall at the James Farley Post Office,[30] and some have proposed moving MSG to other sites in western Manhattan. On February 15, 2013, Manhattan Community Board 5 voted 36–0 against granting a renewal to MSG’s operating permit in perpetuity and proposed a 10-year limit instead in order to build a new Penn Station where the arena is currently standing. Manhattan borough president Scott Stringer said, “Moving the arena is an important first step to improving Penn Station.” The Madison Square Garden Company responded by saying that “[i]t is incongruous to think that M.S.G. would be considering moving.”[31]

In May 2013, four architecture firms – SHoP Architects, SOM, H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture, and Diller Scofidio + Renfro – submitted proposals for a new Penn Station. SHoP Architects recommended moving Madison Square Garden to the Morgan Postal Facility a few blocks southwest, as well as removing 2 Penn Plaza and redeveloping other towers, and an extension of the High Line to Penn Station.[29] Meanwhile, SOM proposed moving Madison Square Garden to the area just south of the James Farley Post Office, and redeveloping the area above Penn Station as a mixed-use development with commercial, residential, and recreational space.[29] H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture wanted to move the arena to a new pier west of Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, four blocks west of the current station and arena. Then, according to H3’s plan, four skyscrapers would be built, one at each of the four corners of the new Penn Station superblock, with a roof garden on top of the station; the Farley Post Office would become an education center.[29] Finally, Diller Scofidio + Renfro proposed a mixed-use development on the site, with spas, theaters, a cascading park, a pool, and restaurants; Madison Square Garden would be moved two blocks west, next to the post office. DS+F also proposed high-tech features in the station, such as train arrival and departure boards on the floor, and apps that would inform waiting passengers of ways to occupy their time until they board their trains.[29] Madison Square Garden rejected the notion that it would be relocated, and called the plans “pie-in-the-sky”.[29]

In June 2013, the New York City Council Committee on Land Use voted unanimously to give the Garden a ten-year permit, at the end of which period the owners will either have to relocate or go back through the permission process.[32] On July 24, the City Council voted to give the Garden a 10-year operating permit by a vote of 47–1. “This is the first step in finding a new home for Madison Square Garden and building a new Penn Station that is as great as New York and suitable for the 21st century,” said City Council speaker Christine Quinn. “This is an opportunity to reimagine and redevelop Penn Station as a world-class transportation destination.”[33]

In October 2014, the Morgan facility was selected as the ideal area for Madison Square Garden to be moved, following the 2014 MAS Summit in New York City. More plans for the station were discussed.[34][35] Then, in January 2016, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a redevelopment plan for Penn Station that would involve the removal of The Theater at Madison Square Garden, but would otherwise leave the arena intact.[36][37]

Events[edit]

Regular events[edit]

Sports[edit]

Madison Square Garden hosts approximately 320 events a year. It is the home to the New York Rangers of the National Hockey League, and the New York Knicks of the National Basketball Association. Before 2020, the New York Rangers, New York Knicks, and the Madison Square Garden arena itself were all owned by the Madison Square Garden Company. The MSG Company split into two entities in 2020, with the Garden arena and other non-sports assets spun off into Madison Square Garden Entertainment and the Rangers and Knicks remaining with the original company, renamed Madison Square Garden Sports. Both entities remain under the voting control of James Dolan and his family. The arena is also host to the Big East Men’s Basketball Tournament and the finals of the National Invitation Tournament. It also hosts select home games for the St. John’s Red Storm, representing St. John’s University in men’s (college basketball), and almost any other kind of indoor activity that draws large audiences, such as the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show and the 2004 Republican National Convention.

The Garden was home of the NBA Draft and NIT Season Tip-Off, as well as the former New York City home of the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus and Disney on Ice; all four events are now held at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. It served the New York Cosmos for half of their home games during the 1983–84 NASL Indoor season.[38]

Many of boxing’s biggest fights were held at Madison Square Garden, including the Roberto Durán–Ken Buchanan affair, the first Muhammad Ali – Joe Frazier bout and the US debut of Anthony Joshua that ended in a huge upset. Before promoters such as Don King and Bob Arum moved boxing to Las Vegas, Nevada, Madison Square Garden was considered the mecca of boxing. The original 18+1⁄2 ft × 18+1⁄2 ft (5.6 m × 5.6 m) ring, which was brought from the second and third generation of the Garden, was officially retired on September 19, 2007, and donated to the International Boxing Hall of Fame after 82 years of service.[39] A 20 ft × 20 ft (6.1 m × 6.1 m) ring replaced it beginning on October 6 of that same year.[40]

Pro wrestling[edit]

Madison Square Garden has been considered the mecca for professional wrestling and the home of WWE (formerly WWF and WWWF).[41] The Garden has hosted three WrestleMania events, more than any other arena, including the first edition of the annual marquee event for WWE, as well as the 10th and 20th editions. It also hosted the Royal Rumble in 2000 and 2008; SummerSlam in 1988, 1991 and 1998; as well as Survivor Series in 1996, 2002 and 2011.

New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW) and Ring of Honor hosted their G1 Supercard supershow at the venue on April 6, 2019, which sold out in 19 minutes after the tickets went on sale.[42] A year later it was announced that New Japan Pro-Wrestling would return to Madison Square Garden alone on August 22, 2020 for NJPW Wrestle Dynasty.[43] In May 2020, NJPW announced that the Wrestle Dynasty show would be postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[44][45]

Concerts[edit]

Madison Square Garden hosts more high-profile concert events than any other venue in New York City. It has been the venue for Michael Jackson’s Bad World Tour, George Harrison’s The Concert for Bangladesh, The Concert for New York City following the September 11 attacks, John Lennon’s final concert appearance (during an Elton John concert on Thanksgiving Night, 1974) before his murder in 1980, and Elvis Presley, who gave four sold-out performances in 1972, his first and last ever in New York City. Parliament-Funkadelic headlined numerous sold-out shows in 1977 and 1978. Kiss, who were formed in the arena’s city and three of whose members were city-born, did six shows during their second half of the 1970’s main attraction peak or “heyday”: four winter shows at the arena in 1977 (February 18 and December 14-16), and another two shows only this time in summer for a decade-ender in 1979 (July 24-25). Billy Joel, another city-born and fellow 1970’s pop star, played his first Garden show on December 14, 1978. Led Zeppelin’s three-night stand in July 1973 was recorded and released as both a film and album titled The Song Remains The Same. The Police played their final show of their reunion tour at the Garden in 2008.

In the summer of 2017, Phish performed 13 consecutive concerts at the venue, which the Garden commemorated by adding a Phish themed banner to the rafters.[46] With their first MSG show taking place on December 30, 1994, the “Bakers’ Dozen” brought the total number of Phish shows there to 52. An additional 12 shows since (4 for each of Phish’s annual New Year’s Eve runs) brings their total MSG performances to 64.[47][48]

Eric Clapton (pictured at the Garden in 2015) has played 45 concerts at the venue since 1968.[49]

At one point, Elton John held the all-time record for the greatest number of appearances at the Garden with 64 shows. In a 2009 press release, John was quoted as saying “Madison Square Garden is my favorite venue in the whole world. I chose to have my 60th birthday concert there, because of all the incredible memories I’ve had playing the venue.”[50] A DVD recording was released as Elton 60—Live at Madison Square Garden.[51] Billy Joel, who broke the record, stated “Madison Square Garden is the center of the universe as far as I’m concerned. It has the best acoustics, the best audiences, the best reputation, and the best history of great artists who have played there. It is the iconic, holy temple of rock and roll for most touring acts and, being a New Yorker, it holds a special significance to me.”[50] Queen played their first concerts at the venue in February 1977. Bob Marley and The Wailers performed in the venue in 1978, 1979 and 1980 as part of Kaya Tour, Survival Tour and Uprising Tour respectively.

The Grateful Dead performed in the venue 53 times from 1979 to 1994, with the first show being held on September 7, 1979, and the last being on October 19, 1994. Their longest run being done in September 1991.[52] Madonna performed at this venue a total of 31 concerts, the first two being during her 1985 Virgin Tour, on June 10 and 11, and the most recent being the two-nights stay during her Rebel Heart Tour on September 16 and 17, 2015. Bruce Springsteen has performed 47 concerts at this venue, many with the E Street Band, including a 10-night string of sold-out concerts out between June 12 and July 1, 2000, at the end of the E Street Reunion tour.

U2 performed at the arena 28 times: the first one was on April 1, 1985, during their Unforgettable Fire Tour, in front of a crowd of 19,000 people. The second and the third were on September 28 and 29, 1987, during their Joshua Tree Tour, in front of 39,510 people. The fourth was on March 20, 1992, during their Zoo TV Tour, in front of a crowd of 18,179 people. The fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth were on June 17 and 19 and October 24, 25, and 27, 2001, during their Elevation Tour, in front of 91,787 people. The 10th through 17th took place between May 21 and November 22, 2005, during their Vertigo Tour, in front of a total sold-out crowd of 149,004 people. The band performed eight performances at the arena in July 2015 as part of their Innocence + Experience Tour, and three performances in 2018 as part of their Experience + Innocence Tour.

The Who have headlined at the venue 32 times, including a four-night stand in 1974, a five-night stand in 1979, a six-night stand in 1996, and four-night stands in 2000 and 2002. They also performed at The Concert for New York City in 2001.[53]

On March 10, 2020, a 50th-anniversary celebration of The Allman Brothers Band entitled ‘The Brothers’ took place featuring the five surviving members of the final Allman Brothers lineup and Chuck Leavell. Dickey Betts was invited to participate but his health precluded him from traveling.[54] This was the final concert at the venue before the Covid-19 Pandemic. Live shows returned to The Garden when the Foo Fighters headlined a show there on June 20, 2021. The show was for a vaccinated audience only and was the first 100 percent capacity concert in a New York arena since the start of the pandemic.[55]

Other events[edit]

It has previously hosted the 1976 Democratic National Convention,[56] 1980 Democratic National Convention,[56] 1992 Democratic National Convention,[57] and the 2004 Republican National Convention,[58] and hosted the NFL Draft for many years (later held at Garden-leased Radio City Music Hall, now shared between cities of NFL franchises).[59][60] Jeopardy Teen Tournament/Celebrity Jeopardy filmed at MSG in 1999 [61] and Wheel of Fortune in 1999 and 2013.[62][63]

The New York Police Academy,[64] Baruch College/CUNY and Yeshiva University also hold their annual graduation ceremonies at Madison Square Garden. It hosted the Grammy Awards in 1972, 1997, 2003, and 2018 (which are normally held in Los Angeles) as well as the Latin Grammy Awards of 2006.

The group, and Best in Show competitions of the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show have been held at MSG every February from 1877 to 2020, which was MSG’s longest continuous tenant although this was broken in 2021 as the Westminster Kennel Club announced that the event will be held outdoors for the first time.[65][66]

Notable firsts and significant events[edit]

The Garden hosted the Stanley Cup Finals and NBA Finals simultaneously on two occasions: in 1972 and 1994.

The Knicks clinched the 1970 NBA Finals at the arena in the seventh game, remembered best for Willis Reed’s unexpected appearance after an injury. The Rangers would later end their 54-year championship drought by winning the 1994 Stanley Cup Finals on home ice. Finally, the 1999 NBA Finals was decided in the Garden, with the San Antonio Spurs defeating the Knicks in five games.

MSG has hosted the following All-Star Games:

NHL All-Star Game: 1973, 1994

NBA All-Star Game: 1998, 2015

WNBA All-Star Game: 1999, 2003, 2006

All American Karate Championships held in 1968 & 1969 won by Chuck Norris 1970 was won by Mitchell Bobrow.

UFC held its first event in New York City, UFC 205, at Madison Square Garden on November 12, 2016. This was the first event the organization held after New York State lifted the ban on mixed martial arts.

Recognition given by Madison Square Garden[edit]

Madison Square Garden Gold Ticket Award[edit]

In 1977 Madison Square Garden announced Gold Ticket Awards would be given to performers who had brought in more than 100,000 unit ticket sales to the venue. Since the arena’s seating capacity is about 20,000, this would require a minimum of five sold-out shows. Performers who were eligible for the award at the time of its inauguration included Chicago, John Denver, Peter Frampton, the Rolling Stones, the Jackson 5, Elton John, Led Zeppelin, Sly Stone, Jethro Tull, The Who, and Yes.[67][68] Graeme Edge, who received his award in 1981 as a member of The Moody Blues, said he found his gold ticket to be an interesting piece of memorabilia because he could use it to attend any event at the Garden.[69] Many other performers have received a Gold Ticket Award since 1977.

Madison Square Garden Platinum Ticket Award[edit]

Madison Square Garden also gave Platinum Ticket Awards to performers who sold over 250,000 tickets to their shows throughout the years. Winners of the Platinum Ticket Awards include: the Rolling Stones (1981),[70] Elton John (1982),[71] Yes (1984),[72] Billy Joel (1984),[73] and The Grateful Dead (1987).[74]

Madison Square Garden Hall of Fame[edit]

The Madison Square Garden Hall of Fame honors those who have demonstrated excellence in their fields at the Garden. Most of the inductees have been sports figures, however, some performers have been inducted as well. Elton John was reported to be the first non-sports figure inducted into the MSG Hall of Fame in 1977 for “record attendance of 140,000” in June of that year.[75] For their accomplishment of “13 sell-out concerts” at the venue, the Rolling Stones were inducted into the MSG Hall of Fame in 1984, along with nine sports figures, bringing the hall’s membership to 107.[76]

Madison Square Garden Walk of Fame[edit]

The walkway leading to the arena of Madison Square Garden was designated as the “Walk of Fame” in 1992.[77] It was established “to recognize athletes, artists, announcers and coaches for their extraordinary achievements and memorable performances at the venue.”[78] Each inductee is commemorated with a plaque that lists the performance category in which his or her contributions have been made.[77] Twenty-five athletes were inducted into the MSG Walk of Fame at its inaugural ceremony in 1992, a black-tie dinner to raise money to fight multiple sclerosis.[79] Elton John was the first entertainer to be inducted into the MSG Walk of Fame in 1992.[80][81] Billy Joel was inducted at a date after Elton John,[82] and the Rolling Stones were inducted in 1998.[83] In 2015, the Grateful Dead were inducted into the MSG Walk of Fame along with at least three sports-related figures.[82][78]

Seating[edit]

Seating in Madison Square Garden was initially arranged in six ascending levels, each with its own color. The first level, which was available only for basketball games, boxing and concerts, and not for hockey games and ice shows, was known as the “Rotunda” (“ringside” for boxing and “courtside” for basketball), had beige seats, and bore section numbers of 29 and lower (the lowest number varying with the different venues, in some cases with the very lowest sections denoted by letters rather than numbers). Next above this was the “Orchestra” (red) seating, sections 31 through 97, followed by the 100-level “First Promenade” (orange) and 200-level “Second Promenade”(yellow), the 300-level (green) “First Balcony”, and the 400-level (blue) “Second Balcony.” The rainbow-colored seats were replaced with fuchsia and teal seats[84] during the 1990s renovation (in part because the blue seats had acquired an unsavory reputation, especially during games in which the New York Rangers hosted their cross-town rivals, the New York Islanders) which installed the 10th-floor sky-boxes around the entire arena and the 9th-floor sky-boxes on the 7th avenue end of the arena, taking out 400-level seating on the 7th Avenue end in the process.

Getting the arena ready for a basketball game in 2005

Because all of the seats, except the 400 level, were in one monolithic grandstand, horizontal distance from the arena floor was significant from the ends of the arena. Also, the rows rose much more gradually than other North American arenas, which caused impaired sightlines, especially when sitting behind tall spectators or one of the concourses. This arrangement, however, created an advantage over newer arenas in that seats had a significantly lower vertical distance from the arena floor.

Read more: How To Plant Marigolds In Amongst The Vegetables As A Companion Plant

As part of the 2011–2013 renovation, the club sections, 100-level and 200-level have been combined to make a new 100-level lower bowl. The 300-level and 400-level were combined and raised 17 feet (5.2 m) closer, forming a new 200-level upper bowl. All skyboxes but those on the 7th Avenue end were removed and replaced with balcony seating (8th Avenue) and Chase Bridge Seating (31st Street and 33rd Street). The sky-boxes on the 9th floor were remodeled and are now called the Signature Suites. The sky-boxes on the 7th Avenue end of the 10th Floor are now known as the Lounges. One small section of the 400-level remains near the west end of the arena and features blue seats. The media booths have been relocated to the 31st Street Chase Bridge.

Capacity[edit]

Basketball[85] Years Capacity 1968–1971 19,500 1971–1972 19,588 1972–1978 19,693 1978–1989 19,591 1989–1990 18,212 1990–1991 19,081 1991–2012 19,763 2012–2013 19,033 2013–present 19,812[1]

Ice hockey[86] Years Capacity 1968–1972 17,250 1972–1990 17,500 1990–1991 16,792 1991–2012 18,200 2012–2013 17,200 2013–present 18,006[1]

Hulu Theater[edit]

The Hulu Theater at Madison Square Garden seats between 2,000 and 5,600 for concerts and can also be used for meetings, stage shows, and graduation ceremonies. It was the home of the NFL Draft until 2005, when it moved to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center after MSG management opposed a new stadium for the New York Jets. It also hosted the NBA Draft from 2001 to 2010. The theater also occasionally hosts boxing matches.

The fall 1999 Jeopardy! Teen Tournament as well as a Celebrity Jeopardy! competitions were held at the theater. Wheel of Fortune taped at the theater twice in 1999 and 2013. In 2004, it was the venue of the Survivor: All-Stars finale. No seat is more than 177 feet (54 m) from the 30′ × 64′ stage. The theatre has a relatively low 20-foot (6.1 m) ceiling at stage level[87] and all of its seating except for boxes on the two side walls is on one level slanted back from the stage. There is an 8,000-square-foot (740 m2) lobby at the theater.

Accessibility and transportation[edit]

The 7th Avenue entrance to Madison Square Garden and Penn Station in 2013

Madison Square Garden sits directly atop a major transportation hub in Pennsylvania Station, featuring access to commuter rail service from the Long Island Rail Road and New Jersey Transit, as well as Amtrak. The Garden is also accessible via the New York City Subway. The A, C, and E trains stop at 8th Avenue and the 1, 2, and 3 trains at 7th Avenue in Penn Station. The Garden can also be reached from nearby Herald Square with the B, D, F, <F>, M, N, Q, R, and W trains at the 34th Street – Herald Square station as well as PATH train service from the 33rd Street station.

See also[edit]

Madison Square Garden Bowl, a former outdoor boxing venue in Queens operated by the Garden company

List of NCAA Division I basketball arenas

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

^ a b c d DeLessio, Joe (October 24, 2013). “Here’s What the Renovated Madison Square Garden Looks Like”. New York Magazine. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

^ Seeger, Murray (October 30, 1964). “Construction Begins on New Madison Sq. Garden; Grillage Put in Place a Year After Demolition at Penn Station Was Started”. The New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

^ “Fred Severud; Designed Madison Square Garden, Gateway Arch”. Los Angeles Times. June 15, 1990. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

^ a b “New York Architecture Images- Madison Square Garden Center”.

^ “Pollstar Pro’s busiest arena pdf” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2017.

^ Esteban (October 27, 2011). “11 Most Expensive Stadiums in the World”. Total Pro Sports. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

^ Mendelsohn, Joyce. “Madison Square” in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN +61404532026., p. 711–712

^ a b c d e “Madison Square Garden/The Paramount”.

^ a b Federal Writers’ Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. ISBN +61404532026. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), pp. 330–333

^ Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike, Gotham: A History of New York to 1989. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN +61404532026

^ “Madison Square Garden III” on Ballparks.com

^ Schumach, Murray (February 14, 1948).Next and Last Attraction at Old Madison Square Garden to Be Wreckers’ Ball, The New York Times

^ Eisenband, Jeffrey. “Remembering The 1948 Madison Square Garden All-Star Game With Marv Albert”. ThePostGame. Retrieved July 5, 2015.

^ “Investors Get Madison Sq. Garden”. Variety. February 4, 1959. p. 20. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Archive.org.

^ New York Times: “Irving M. Felt, 84, Sports Impresario, Is Dead” By AGIS SALPUKAS September 24, 1994

^ Massachusetts Institute of Technology: “The Fall and Rise of Pennsylvania Station -Changing Attitudes Toward Historic Preservation in New York City” by Eric J. Plosky 1999

^ Tolchin, Martin (October 29, 1963). “Demolition Starts At Penn Station; Architects Picket; Penn Station Demolition Begun; 6 Architects Call Act a ‘Shame’ “. The New York Times. ISSN +61404532026. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

^ Muschamp, Herbert (June 20, 1993). “Architecture View; In This Dream Station Future and Past Collide”. The New York Times. ISSN +61404532026. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

^ “Rangers on Road in the Bronx? Money May Be Why”. New York Times. January 25, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

^ Staple, Arthur (April 3, 2008). “MSG Executives Unveil Plan for Renovation”. Newsday. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

^ David Mayo (April 9, 2017). “With two arena closings in two days, Detroit stands unique in U.S. history”. MLive. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

^ John Eligon (February 22, 2008). “Joe Louis and Harlem, Connecting Again in a Police Athletic League Gym”. The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

^ Feirstein, Sanna (2001). Naming New York: Manhattan Places & how They Got Their Names. New York University Press. p. 110. ISBN +61404532026. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

^ the Rangers started the 2011–12 NHL season with seven games on the road before playing their first hom game on October 27.Rosen, Dan (September 26, 2010). “Rangers Embrace Daunting Season-Opening Trip”. National Hockey League. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

^ The Knicks played the entire 2012 NBA preseason on the road.Swerling, Jared (August 2012). “Knicks preseason schedule announced”. ESPN. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

^ “Madison Square Garden – Official Web Site”. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010.

^ Bultman, Matthew; McShane, Larry (November 26, 2010). “Madison Square Garden to Add Pedestrian Walkways in Rafters as Part of $775 Million Makeover”. New York Daily News. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

^ Scott Cacciola (June 17, 2010). “Cultivating a New Garden”. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

^ a b c d e f Hana R. Alberts (May 29, 2013). “Four Plans for a New Penn Station Without MSG, Revealed!”. Curbed. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

^ “Moynihan Train Hall Finally Opens in Manhattan”. NBC New York. December 31, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

^ Dunlap, David (April 9, 2013). “Madison Square Garden Says It Will Not Be Uprooted From Penn Station”. The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

^ Randolph, Eleanor (June 27, 2013). “Bit by Bit, Evicting Madison Square Garden”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

^ Bagli, Charles (July 24, 2013). “Madison Square Garden Is Told to Move”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

^ Hana R. Alberts (October 23, 2014). “Moving the Garden Would Pave the Way for a New Penn Station”. Curbed. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

^ “MSG & the Future of West Midtown”. Scribd.

^ Higgs, Larry (January 6, 2016). “Gov. Cuomo unveils grand plan to rebuild N.Y. Penn Station”. The Star-Ledger. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

^ “6th Proposal of Governor Cuomo’s 2016 Agenda: Transform Penn Station and Farley Post Office Building Into a World-Class Transportation Hub”. Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

^ Yannis, Pat (March 8, 1984). “Hartford Shift Seen For Indoor Cosmos”. The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2016 – via newyorktimes.com.

^ Baker, Mark A. (2019). Between the Ropes at Madison Square Garden, The History of an Iconic Boxing Ring, 1925–2007. ISBN +61404532026.

^ Fine, Larry (September 19, 2007). “Madison Square Garden ring out for count after 82 years”. Reuters.

^ Sullivan, Kevin (July 12, 2014). “Madison Square Garden really is the mecca of wrestling arenas”. yesnetwork.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

^ “History has Been Made: ROH & New Japan Sell Out Madison Square Garden – PWInsider.com”. www.pwinsider.com.