#Battle of Falkirk

Photo

'The Battle of Falkirk Muir 1746' - oil on canvas, 46" x 32" by Chris Collingwood, 2021.

#battle of falkirk#falkirk#jacobite#jacobites#jacobite rising#jacobite risings#1745#1746#the 45#british army#redcoat#redcoats#18th century#history#military history

25 notes

·

View notes

Video

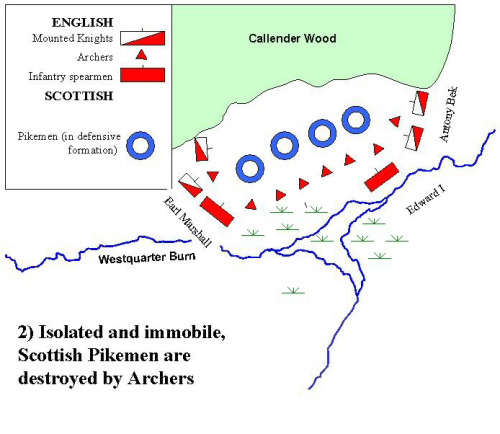

Battle of Falkirk 1298 Memorial Event.

A taster of what this years memorial was all about, did you not make it? Like what you see, well write it down in your diaries, next year will mark the 725th anniversary of the Battle of Falkirk and there are big plans being developed to mark the day .........

Keep your eyes on the Society of John de Graeme's social media pages here

@John_De_graeme on Twitter and

https://www.facebook.com/societyofjohndegraeme on Facebook.

#Scotland#scottish#history#reenactments#stalls#memorials#Falkirk#Battle of Falkirk#medieval history#2023

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

23rd August

William Wallace

Source: GettyImages/ BBC

On this day in 1305 Sir William Wallace was executed. Wallace was a middle-ranking knight of probable Norman descent, but had become disgruntled with the rule of the English whose king, Edward I, had intervened in Scotland following a royal succession crisis. Wallace’s unhappiness converted into outright rebellion following the murder of his wife by an English sheriff. Wallace avenged himself by killing the sheriff but then became a wanted man and so set about raising an army of Scottish patriots determined to drive the English from their country. He nearly succeeded: after destroying an English army at the battle of Stirling Bridge, Wallace led his victorious men in a large scale raid into northern England, and declared Scotland free. However King Edward himself (known in a giveaway as the “Hammer of the Scots”) came against the rebels and they were comprehensively defeated at the battle of Falkirk. Wallace was captured and put to death by the grisly new punishment of being hung (although not to death), drawn (disembowelled while still alive) and quartered (the body hacked to pieces and the remnants displayed in various locations across the country).

Wallace is depicted in legend as a dashing, freedom-loving man of the people, not least in the wildly historically inaccurate film, Braveheart. In reality, he had far more in common with his Scottish and English noble opponents than he did with the Scottish peasantry, but his fight has gone down in legend as one of the earliest examples of assertive nationalism. It undoubtedly paved the way for the eventual freeing of Scotland from English interference by Robert the Bruce.

0 notes

Note

How come the longbow is so associated with the English and their use of the longbow?

I imagine that there have been multiple societies that used the longbow (before or at the same time as the English), but it seems that the English are the most well known users of the longbow (at least in popular culture/thought).

The longbow was originally Welsh, but the English very quickly adopted it as one of their main weapons of war during and after the Edwardian conquest of Wales - that campaign ended in 1283, and by the time of the Battle of Falkirk in 1298, we see the English army now mainly made up of longbowmen (a lot of them Welshmen).

Moreover, the English monarchy enacted laws that reinforced this shift to a longbow-based army: the original Assize of Arms of 1181 had focused on requring freemen of England to own chainmail (or gambesons if you owned less than ten marks), helmets (or just an iron cap if you had ten marks or less), and lances as their main weapon. By the Assize of Arms of 1252, freemen with nine marks or more were required to "array with bow and arrow." By the time of the Statute of Winchester of 1285, even the poorest freemen is expected to have "bows and arrows out of the forest, and in the forest bows and pilets."

Thus, when Edward III starts up the Hundred Years War, the armies that win stunning victories at Crecy and Poitiers (and establish the lasting associaion between England and the longbow) were based on his grandfather's model. Edward would further reinforce royal policy towards longbows by enacting the Archery Law of 1363, which required that "every man … if he be able-bodied, shall, upon holidays, make use, in his games, of bows and arrows… and so learn and practise archery." Thus, longbow practice every Sunday and feast/saint's day became mandatory in England.

The English love affair with the longbow also continued much longer than in other nations. Even after the French began to use cannons against the formations of English longbowmen, and thus regained the upper hand in the Hundred Years War, (something often attributed to their adoption of the longbow, but in reality artillery was the main French adaptation) the English kept on fielding armies of mostly longbowmen. The Battle of Flodden in 1513 was largely fought with longbows; when Henry VIII's flagship the Mary Rose went down in 1545 she had 250 longbows on board (which form the material basis for a lot of our archaelogical understanding of medieval longbows); when the English militia was called up to fight the Spanish Armada in 1588, longbowmen still made up about 10% of their forces.

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

Will you do me a favor and rant about anything you want?

omg ok let me tell you about andrew moray and why william wallace ended up getting credit for his military victories when moray was in fact a far better soldier and tactician who would likely be even more infamous than wallace had he survived the battle of stirling bridge. i will preface this by saying that there is very little research let alone primary sources on this man but he's been an interest of mine for a decade now and i hope to publish a book on him when i graduate. anyway

i always say that william wallace was the churchill of the scottish wars of independence. what i mean by this is that he was seen as a fantastic war time leader at home; as far as we know and can assume he apparently had a way with words and winning people over, and knew how to keep up morale among the people and the soldiers. now while churchill did have military experience, he wasn't really suited for anything other than wartime office. he didn't have what it took for anything that lay outwith being the voice and face that people needed during a war. and similarly wallace was (supposedly) a great orator and exactly what the people needed during a time of hardship, but he really didn't have what it took to do much else. in this case what i mean is that william wallace was not, in my opinion, a particularly strong military leader at all. there's no evidence that he had any military training and his tactics in battle don't always seem particularly strong or well thought out to me. in the leadup to stirling bridge he got by and did well, but i absolutely stand by the notion that this alone was just not enough. he needed a true soldier to secure him his victory at stirling

ENTER ANDREW MORAY. now this guy was born and trained to be a knight. as the son of an influential nobleman he almost certainly received formal military training when he was young. not long before the battle of stirling bridge he and his father were imprisoned by the english but moray managed to escape. the fact he was able to do this and also somehow get back to scotland is already pretty telling of his survival skills i would say. he started up a pretty successful rebellion in the north of scotland and was clearly a real threat to the english if their correspondence among each other is anything to go by. i won't go into too much detail but moray managed to get a lot more done in the north with less support than what wallace achieved in the south with the aid of the feudal leaders there. moray ended up combining his army with william wallace's to fight the english at stirilng in 1297

now we do not know every detail of this battle of course and i want to make it clear that i'm not trying to state any concrete facts here. but when you look at the tactics deployed at stirling bridge (the idea of 'trapping' the english and ambushing them rather than moving to fight in schiltron formations on open ground), we see a game plan FAR MORE reminiscent of the fighting style of a trained and experienced knight; not the usual tactics of wallace. again that's just a little theory of mine, but i think it's very notable

now here's where things go to shit. the scots win at stirling bridge, but moray is wounded in battle and dies. there's no doubt in my mind that he was the driving force behind the victory at stirling, and i think it is EXTREMELY telling that after his death william wallace's military career began to rapidly decline. he lost his first major battle (falkirk) after moray's death (surprise surprise, by using the schiltron formations that were pointedly avoided at stirling) and while this is in part due to the advantages of the english army i think it's worth noting. this loss had a profound impact for wallace and he never fully recovered, dying around seven years later or so

i am fully convinced that if moray had lived everything would've turned out entirely differently. maybe wallace himself would've survived longer too. wallace just did not have the background and skills needed to maintain his pattern of success. he and moray made the perfect double act and without moray there just wasn't enough left to keep the scots standing. moray never received any of the credit he deserves for his role in the war and the fact that almost no one has even heard of him infuriates me because he was SO MUCH BETTER as a military commander than wallace. but i have always said in regards to history that people want a good story more than they want the truth. they'd rather hear about the rebellious underdog who came from nothing and took a more unconventional path toward victory than a bog standard knight with formal training and a textbook background. but i still think moray could've been a lot more than wallace was if he'd survived at stirling, and i think the fact that he's more recently been referred to as 'the greatest threat to the english government' during his time is telling. i hope one day i can access the sources i need to be able to write more about him because i WILL become the Token Andrew Moray Historian if it is the last thing i do

#anyway.#thank you SO FUCKING MUCH for asking me this by the way. i squealed with delight when i saw it#i have so many things i could rant about forever. all history stuff and mostly caesar but uh. yeah#anyway PLEASE GOD ask me about stuff. history or caesar lore or anything idk. thank you for asking me this#casbah history tag

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's like the 800 and something anniversary of the battle of Falkirk so now there's a fucking town crier outside my work

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Let us assume, picking up our discussion of information last time, that our army is formed up into its battle array (pre-planned the night before, recall) and is advancing and our general has just now noticed something that demands a change in the plan. It could be a dangerous enemy attack (perhaps on the flank) or an opportunity to split the enemy line.

Whatever it is, our general needs to make some alteration to the battle plan. It is almost certainly a fairly minor alteration, as with a battle line anywhere from a kilometer to several kilometers long, it would, for instance, take far too long to shuffle the right-to-left order of the line just due to the marching time involved. Nevertheless, the general needs to issue an unplanned, on-the-spot command; how does he do it?

The first option, of course, is shouting. The problem here is obvious: how is the commander’s command to be heard? Interestingly, there has been a fair bit of research by ancient historians looking at the question of how many people can possibly hear a short address unaided by modern loudspeakers and the like; figures vary but generally a few thousand if they are reasonably compact and quiet. That might work for a general’s pre-battle speech, delivered before the army advances, but it will not do for an army that is already in motion, much less once the chaos of battle has begun. Thousands of men marching (let alone fighting!) are noisy!

The modern solution to this problem is radio, but of course that’s hardly available to our pre-modern commander. Instead, to judge by films, the mind quickly jumps to signal flags. I am reminded of Braveheart (1995)’s rendition of the Battle of Falkirk, where Edward I uses signal flags to order his archers forward. HBO’s Rome also does this in its version of the Battle of Philippi, with flags being jostled and then pointed forward to signal the advance.

Unfortunately, signal flags – as distinct from unit flags (which we’ll come back to in a moment) – have a few key problems, the most notable of which is that no one will be looking at them: after all the army is advancing, the soldiers are looking forward but signal flags (again, as opposed to unit flags) are going to be behind them, not placed out in the middle of No Man’s Land between the armies.

As a result, signal flags are useful for sending information long distances (in a chain of stations or operators), for instance from one commander at distance to another, but not in battle; operational, rather than tactical tools. In practice, the use of signal flags like this is confined to the modern era; the first successful ‘optical telegraphs’ (as iterations on things like smoke signals and fire relays) date to the late 18th century.

Unit flags – a banner or other big, obvious symbol (like a statue of an eagle on a stick) – are more useful. These can be positioned at the front of a unit, typically at its center. If it advances, then the soldiers in the unit also know to advance, following the standard they can see (because it is elevated, large and visible) even if they cannot hear the orders.

There are two complications here though: first, the unit banner or flag is a relatively late innovation in antiquity, really only coming into its own with the Romans. The Achaemenids may have used some kinds of ensigns or standards, but the Greeks do not seem to have done. Instead our first really good documentation of something like a battle flag comes from the Romans: each legion had a signa (eventually standardized to the legionary eagle, the aquila), which was a shiny metal statue mounted on a poll so it could be easily seen.

Units of the legion broken off to do other things might instead follow a less impressive cloth banner, a vexillum, by which such detachments became known as vexillationes. But the broader problem is that of course your general may not be particularly close to your flags (or other standards) which are generally at the front-center of each component unit of your army. The flags may allow a subordinate officer to ‘drive’ the unit over the battlefield – and that’s good – but it doesn’t let the general tell that officer what to do.

A better option is music, but once again development seems to come fairly late in antiquity. Greek hoplites seem to have advanced to the music of the aulos, a double-reeded flute-like instrument; given the limitations of the instrument it is generally assumed it was used to keep time (so everyone marched in step) not transmit orders. Once again, a more complex system of musical signalling seems to come with the Romans, at least as detailed by Vegetius.

Vegetius (2.22) notes three different kinds of horn instruments used by a legion: the tubicen was used to sound charge and retreat, the cornicen regulated the movement of the signa (so ‘advance’ or ‘halt’), while the buccina was used mostly for camp signals: sounding watches or assemblies. It’s a system that is akin to later bugle calls, but note that the orders it can give are limited to a relative handful of prearranged signals: advance, halt, charge, retreat, assemble, change shift and so on.

…Of course if those instruments are sounding on a per-unit basis (and they are) that means you still have the problem of getting the order from the general to the instruments for the unit in question. And fundamentally here, the technology is – as I tell my students – man-on-horse. The particular fellow on the horse may be a dedicated messenger (if your military organization has those) or a subordinate officer or it may be the general himself.

But it is important to note now the limitations of this sort of system and we can use what we know of the Roman command and control system (as noted, one of the more developed of such systems prior to gunpowder) to get a sense of them. Let’s say the general realizes there is a problem on his flank and he needs a unit (probably here we’re talking a cohort or a maniple, not a legion) to change what it is doing.

First off, the order needs to get within shouting range of the unit’s commander (in this case a senior centurion). The general can either go themselves or send a messenger; both options have their downsides. If the general goes himself he is essentially removing himself from observing or commanding the rest of the battle, but a common problem with sending a junior subordinate is that the unit commander may not respect or feel the need to obey that subordinate (written orders can help with this, but now we’re bringing in questions of literacy). Of course both a messenger or a general in transit may also well be killed, which will prevent the order from being received!

In either case, the message is going to move at galloping speed, which is around 40km/h, meaning that it may take several minutes for the general or messenger to navigate to the spot. That doesn’t sound so bad, but battles with contact weapons do not typically go for hours and hours; Pydna (168) was, as noted last week, decided in about an hour total!

Of course a battle might be longer (or shorter!) than this, though much of that extra time is likely pre-battle skirmishing – the actual direct press of infantry formations in shock rarely lasts long because of the terror of it (and to a lesser extent its lethality; we’ll return to the balance of terror and lethality next time). Imagine if you were playing a Total War game and your input delay was, say, five minutes long in a battle that might only last an hour or two.

But of course galloping time isn’t the end of it. The message now has to be conveyed to the unit. In the Roman system, that means the messenger needs to find the appropriate centurion, explain the order to him and then ideally that fellow will then signal the instruments and signa to act accordingly – but even then, those instruments and signa only have a handful of prearranged signals available.

Anything more complicated will need to be shouted down the line the old fashioned way (as we know, for instance, the Spartans did for lack of almost any of the rest of this apparatus of command, Xen. Lac. 13.9). Needless to say that means that giving any complex order to a unit already engaged or about to be engaged is going to mean starting by signalling retreat and then attempting to regroup the unit; regrouping an already retreating unit is one of the most difficult tasks on a battlefield and is rarely performed successfully in an unplanned fashion (even in an planned fashion it goes wrong as often as it goes right).

(This is, by the by, why reserves are so important. An unengaged unit hanging behind the lines can be given new orders far, far easier than a unit that is already engaged or about to be. And indeed, those familiar with the Roman system of fighting with its three lines of heavy infantry will note that it is a system heavy on reserves.

Indeed, the manipular legion essentially assumes it will be necessary to retreat and regroup the first line of heavy infantry (the hastati) behind the second (the principes) and plans and drills for that. Note how the Roman command culture, the Roman fighting method and the actual apparatus of messengers, signa, instruments and junior officers all align here – that’s common because these sort of institutions tend to co-evolve)

By contrast we may compare a Greek hoplite army in the Classical Period. It has no battle flags or ensigns and the general is expected to fight on foot. In the past I’ve described the resulting phalanx as an ‘unguided missile‘ and this is a big reason why. That’s not to say hoplite generals never exerted command on the battlefield – better generals might keep a reserve to be rushed to important points (as Pagondas does at the Battle of Delium in 424 BC). But for the most part, once a hoplite general formed up the army and hit ‘go,’ they had very little control over the army.”

- Bret Devereaux, “Commanding Pre-Modern Armies, Part II: Commands.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Strength of a High and Noble Hill (Outlander Story) Timeline - 17th and 18th Centuries

Thought I would a timeline here as my timeline is a mix of my own stuff and the show/books. This will be getting updated as I go along. This is also for our own sanity to look back at. Advice is not to read if not up to date with current story as spoilers. Been split into two.

(19th and 20th Centuries)

1691 - Brian Fraser is born

1695 - Ellen Catriona Sileas Mackenzie is born

1716 - Brian and Ellen marry and William Simon Murtagh Mackenzie Fraser is born (Brian/Ellen)

1719 - Janet (Jenny) Flora Arabella Fraser is born (Brian/Ellen)

May 1720 - Ian Murray is born

1st May 1721 - James (Jamie) Alexander Malcolm Mackenzie Fraser is born (Brian/Ellen)

1726 - Laoghaire MacKenzie is born

1727 - George II becomes King of Great Britain and Ireland and Jamie’s brother William dies of smallpox

1729 - Lord John Grey is born and Ellen Fraser dies giving birth to Robert Brian Gordon Mackenzie Fraser (Brian/Ellen) who dies as well

May 1st 1733 - Gillian Edgars/Geillis Duncan arrives through the stones from 1968

1735 - Fergus Claudel Fraser is born

1739 - Geneva Dunsany Ransom is born

October 1740 - Jamie is captured by Captain Jack Randall, Brian Fraser dies of a stroke and Jamie flees to France

1740 - Jenny marries Ian Murray

1741 - James (Young Jamie) Alexander Gordon Fraser Murray is born (Jenny/Ian)

2nd May 1743 - Claire arrives through the stones at Craigh na Dun and meets Jamie who's returned to Scotland

June 1743 - Claire and Jamie get married

November 1743 - Margaret (Maggie) Ellen Fraser Murray is born (Jenny/Ian)

January 1744 - William Buccleigh Mackenzie is born (Dougal/Geillis)

February 1744 - Claire and Jamie leave for France

12th May 1744 - Brian Ian Fraser is born in Paris

August 1744 - Jamie returns from the Bastille

September 1744 - Arrive at Lallybroch

February 1745 - Katherine (Kitty) Mary Fraser Murray born (Jenny/Ian)

July 1745 - Battles begin

17th September 1745 - The Jacobites take Edinburgh

September 1745 - Lord John and Brian meet

21st September 1745 - Jacobite victory at Prestonpans

December 1745 - The Jacobites take Derby few hundred miles from London then retreat north

17th January 1746 - Last Jacobite victory at Falkirk

April 16th 1746 - The Culloden near Inverness defeat and Brian almost 2 sent to future through the stones at Craigh na Dun with Claire (2 months pregnant) and appear mid April 1948

1748 - Michael and Janet Fraser Murray born (Jenny/Ian)

December 1749 - Caitlin Fraser Murray born and died (Jenny/Ian)

1751 - Marsali Jane MacKimmie is born (Simon/Loaghaire)

November 15, 1752 - Young Ian James Fitzgibbons Fraser Murray born (Jenny/Ian)

February 1753 - Fergus loses his hand to a British soldier

16th May 1753 - Jamie enters Ardsmuir Prison

1755 - Lizzie Wemyss born (Joseph)

September 1756 - Jamie arrives at Helwater

January 9th 1758 - William (Willie) Clarence Henry George Ransom is born (Geneva/Jamie) and Geneva Dunsany Ransom dies

1760 - Rachel Hunter is born

25th October 1760 - King George II dies and his grandson succeeds him as George III

July 1764 - Jamie leaves Helwater

Early 1765 - Jamie marries Laoghaire but soon moves to Edinburgh

July 10th 1765 - William Tryon becomes governor of North Carolina

1766 - Rollo is born

November 1766 - Claire comes through stones at Craigh na Dun from 1968 leading to Jamie’s annulment to Laoghaire

Spring 1767 - Fergus and Marsali marry

September 1767 - Jamie and Claire settling on newly established Fraser's Ridge

December 1767 - Germain Alexander Claudel Mackenzie Fraser is born (Fergus/Marsali)

May 1769 - Brian and Ellen come through the stones at Craigh na Dun

June 1769 - Meet the Murray's

July 1769 - Brian and Ellen meet Lizzie Wemyss and travel to the US

September 1769 - Meet with Roger in US, Bonnet’s attack then find Jamie and Claire then meet Young Ian, Fergus and Marsali and later Murtagh

November 1769 - It’s revealed Ellen is pregnant and Roger is sold to the Mohawks

December 1769 - Move to River Run as Claire, Jamie and Ian look for Roger

5th March 1770 - Boston Massacre

March 1770 - Re-meet Lord John

April 1770 - Fergus and Marsali arrive at River Run on their way to Frasers’ Ridge

May 1770 - Claire and Jamie return (Ian has been adopted by Kanyen’kehaka) and Jeremiah (Jem or Jemmy) Alexander Ian Fraser MacKenzie is born (Ellen/Roger)

June 1770 - Roger returns to Fraser’s Ridge

September 1770 - Joan Laoghaire Claire Fraser is born (Fergus/Marsali) and Hillsborough Riot

October 1770 - Ellen and Roger's wedding, the Gathering at Mount Helicon and Lord John comes with news of Bonnet then Fiery Cross

December 1770 - Building a Militia to hunt regulators (Beardsley's and Brownsville) then orders to dismantle

1 note

·

View note

Text

Culloden

Andrew Lang

Dark, dark was the day when we looked on Culloden

And chill was the mist drop that clung to the tree,

The oats of the harvest hung heavy and sodden,

No light on the land and no wind on the sea.

There was wind, there was rain, there was fire on their faces,

When the clans broke the bayonets and died on the guns,

And 'tis Honour that watches the desolate places

Where they sleep through the change of the snows and the suns.

Unfed and unmarshalled, outworn and outnumbered,

All hopeless and fearless, as fiercely they fought,

As when Falkirk with heaps of the fallen was cumbered,

As when Gledsmuir was red with the havoc they wrought.

Ah, woe worth you, Sleat, and the faith that you vowed,

Ah, woe worth you, Lovat, Traquair, and Mackay;

And woe on the false fairy flag of Macleod,

And the fat squires who drank, but who dared not to die!

Where the graves of Clan Chattan are clustered together,

Where Macgillavray died by the Well of the Dead,

We stooped to the moorland and plucked the pale heather

That blooms where the hope of the Stuart was sped.

And a whisper awoke on the wilderness, sighing,

Like the voice of the heroes who battled in vain,

"Not for Tearlach alone the red claymore was plying,

But to bring back the old life that comes not again."

0 notes

Text

The ‘45

For Scotland on St. Andrew’s Day

Grey, the sky an endless grey on this cold, Scottish morn, with a soft, silent drizzling of rain, tis Scotland,

The wind blows as softly along the moor with the grassing swaying back and yon talking to us warning,

Hearts full of righteousness and devotion to our ancient home, hearing only the rage of war agin our oppressors,

We are all here, ready to wage war against the bloody butcher sent to tame and subdue our clans …our highlands

Confident, confident we are with victory behind us and the Bonnie Prince afore us standing solid on our ground, our Scotland,

The tall grass continues to wave to us desperately…telling us what? It feels like …not now? Not here?

Blowing wind whispers in our ears and gently laments unto us what might happen here at Culloden,

There is doubt among some as is the case when men gather to wage war and we war for our freedom

Our backs stiffen in the cold, our legs ache, our bellies cry with hunger from an overnight double time March,

Through our affliction our hearts burn with anticipation that today will be the day that Scots be free,

The names are known to us all: Prestonpons, Bannockburn, Stirling, Falkirk and a dozen more where blood be shed,

All those battles lead us here to Culloden Moor, a place that will forever find a home in the hearts of Scotsmen

The claymores are hungry this grey morn not just for English blood, but for the breath of free men that we will be,

Suddenly, lines of red coats fill the horizon and slowly march towards us, all with muskets nae with halberds,

We don’t see that …our blood rises, angry for five hundred years tired of the meddlesome oppression,

Our legs can fly, our backs are strong, Mackenzie, Macdougall, McGregor, Campbell, Stewart have prayed for this day

Like the tide being held back by a broom our rage spills forth through the damp, muddy moor though we feel light like feathers,

We hear our screams and the fusillade of English cannon and see the smoke erupt from infinite muskets firing in unison,

The screams increase in number and volume, but they are not defiant …they’re screams of blood and pain,

The smoke fills the air and the grass becomes slippery with blood, but no Highlander retreats, they push forth it is freedom or death,

In just a few minutes, the field grows silent save for the moaning of those wounded here within the moor,

They cry but for a small time as English dirks are drug across the necks of my comrades as the blood of Scotland spills on the ground,

The grass still waves and the wind still whispers as I lay dying on the ground, looking up a the grey sky,

The fronds cool my brow and the wind softly says in my ear, “we are all Scotland, this is not the end others will rise …rest now

The blood settles in the ground and will be part of the growth from spring and Scotland will grow,

Names will be remembered and the name of Culloden Moor will haunt and inspire Scots for centuries to come,

We will nae be silent, we will nae submit, from Hadrians wall to Skye we will always be this land,

I close my eyes and dream of the heroes made today and what marvelous scion will hold this day sacred

#open mind#retirement#coffetime#stress#change#teacher#i need friends#health#writing#education#culloden#scot#scotland#scottish

0 notes

Text

Events (before 1900)

838 – Battle of Anzen: The Byzantine emperor Theophilos suffers a heavy defeat by the Abbasids.

1099 – First Crusade: Godfrey of Bouillon is elected the first Defender of the Holy Sepulchre of The Kingdom of Jerusalem.

1209 – Massacre at Béziers: The first major military action of the Albigensian Crusade.

1298 – Wars of Scottish Independence: Battle of Falkirk: King Edward I of England and his longbowmen defeat William Wallace and his Scottish schiltrons outside the town of Falkirk.

1342 – St. Mary Magdalene's flood is the worst such event on record for central Europe.

1443 – Battle of St. Jakob an der Sihl in the Old Zürich War.

1456 – Ottoman wars in Europe: Siege of Belgrade: John Hunyadi, Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary, defeats Mehmet II of the Ottoman Empire.

1484 – Battle of Lochmaben Fair: A 500-man raiding party led by Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany and James Douglas, 9th Earl of Douglas are defeated by Scots forces loyal to Albany's brother James III of Scotland; Douglas is captured.

1499 – Battle of Dornach: The Swiss decisively defeat the army of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.

1587 – Roanoke Colony: A second group of English settlers arrives on Roanoke Island off North Carolina to re-establish the deserted colony.

1594 – The Dutch city of Groningen defended by the Spanish and besieged by a Dutch and English army under Maurice of Orange, capitulates.

1598 – William Shakespeare's play, The Merchant of Venice, is entered on the Stationers' Register. By decree of Queen Elizabeth, the Stationers' Register licensed printed works, giving the Crown tight control over all published material.

1686 – Albany, New York is formally chartered as a municipality by Governor Thomas Dongan.

1706 – The Acts of Union 1707 are agreed upon by commissioners from the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland, which, when passed by each country's Parliament, leads to the creation of the Kingdom of Great Britain.

1793 – Alexander Mackenzie reaches the Pacific Ocean becoming the first recorded human to complete a transcontinental crossing of North America.

1796 – Surveyors of the Connecticut Land Company name an area in Ohio "Cleveland" after Gen. Moses Cleaveland, the superintendent of the surveying party.

1797 – Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Battle between Spanish and British naval forces during the French Revolutionary Wars. During the Battle, Rear-Admiral Nelson is wounded in the arm and the arm had to be partially amputated.

1802 – Emperor Gia Long conquers Hanoi and unified Viet Nam, which had experienced centuries of feudal warfare.

1805 – Napoleonic Wars: War of the Third Coalition: Battle of Cape Finisterre: An inconclusive naval action is fought between a combined French and Spanish fleet under Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve of France and a British fleet under Admiral Robert Calder.

1812 – Napoleonic Wars: Peninsular War: Battle of Salamanca: British forces led by Arthur Wellesley (later the Duke of Wellington) defeat French troops near Salamanca, Spain.

1833 – The Slavery Abolition Act passes in the British House of Commons, initiating the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire.

1864 – American Civil War: Battle of Atlanta: Outside Atlanta, Confederate General John Bell Hood leads an unsuccessful attack on Union troops under General William T. Sherman on Bald Hill.

1893 – Katharine Lee Bates writes "America the Beautiful" after admiring the view from the top of Pikes Peak near Colorado Springs, Colorado.

1894 – The first ever motor race is held in France between the cities of Paris and Rouen. The fastest finisher was the Comte Jules-Albert de Dion, but the "official" victory was awarded to Albert Lemaître driving his three-horsepower petrol engined Peugeot.

0 notes

Video

Wallacestone

A wee clip of my flag at the Wallacestone.

Falkirk was the site of William Wallace's last battle in command of the Scots army.

On 22nd July 1298 he faced the English army, commanded by Edward I. The Scots were defeated and many thousands were killed. The battle is marked by a monument at Wallacestone, which is named after the stone from which Wallace is reputed to have overseen the battle

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

WILLIAM WALLACE - THE BATTLE OF FALKIRK - CLAN CARRUTHERS CCIS

WILLIAM WALLACE AND THE BATTLE OF FALKIRK

Despite his injuries the King was in the saddle before dawn.

As morning was breaking the troops filed through the silent streets of Linlithgow and out into the open country beyond. From a hill not far away came the gleam of spears, but when the English vanguard came up they found that the spearmen had retreated.

Tents were pitched on the…

View On WordPress

#ANCIENT AND HONORABLE CLAN CARRUTHERS#CARRUTHERS#CARRUTHERSLAND#CLAN CARRUTHERS#CLAN CARRUTHERS CCIS#KING EDWARD#ROBERT DE BRUS#SCOTLAND BORDERS#SCOTTISH BORDERS#WILLIAM WALLACE

0 notes

Note

Recently read your post about each of the kingdom's fighting style and you said the Ironborn had outdated shield wall techniques. So I guess my question is, what makes it outdated, and is there a difference from an ancient Greek Hoplite phalanx vs a Norman shield wall?

So the issue with the Ironborn relying on shield walls - a military strategy that was characteristic of the Early Midde Ages - is that they are almost entirely made up of melee infantry (mostly spearmen and axemen) and have relatively few archers and no cavalry. The rest of Westeros have moved on to a Late Medieval paradigm of warfare that stresses a combined arms approach which relies on a mix of knightly cavalry, more advanced melee infantry (men-at-arms, pikemen, etc.), and archers who work in concert, with melee infantry protecting archers from cavalry, archers targeting blocks of infantry, and cavalry attempting to break enemy infantry often by attacking from the flanks or rear.

A Vikinger-style shieldwall is extremely vulnerable to this Late Medieval army. For one thing, we know that Ironborn don't have the discipline to hold the shieldwall together in the face of a cavalry charge - and when infantry formations break, they can be utterly destroyed as happened at the Battle of Hastings. Moreover, even if the Ironborn could hold their formation, the mere presence of cavalry means they have to stretch their lines to protect their flanks and rear, which means they then have a much thinner line with which to oppose the enemy's infantry.

Likewise, if an army made up entirely of melee infantry shieldwalls come up against large numbers of archers who are supported by knights and/or infantry, they can be absolutely decimated as the archers easily target their slow-moving tightly-packed formations who can't retaliate out of fear of counter-attack from the cavalry, as happened at the Battle of Falkirk.

As to the difference between shieldwalls and phalanxes, I answered that question here.

#asoiaf#asoiaf meta#ironborn#shield wall#military history#vikings#early middle ages#late middle ages

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Wallace Marker in Broxburn, Scotland

Fifteen miles west of Edinburgh lies Almondell and Calderwood Country. Open all year around and free to visit, this spacious green wilderness area covers 220 acres of woodland and riverside walks. It is here that you will find not one, but two rather unusual carved rock slabs dating from the 18th century. The first is much easier to locate and can be found downstream from the Almondell Bridge on the southern end, following the "Red" walking route. After walking along the river and crossing over a wooden footbridge, you'll find a stone that reads: MARGARET COUNTESS OF BUCHAN DEDICATED THIS FOREST TO HER ANCESTOR SIR SIMON FRASER OCTOBER XV MDCCLXXXIV Sir Simon Fraser of Oliver and Neidpath fought alongside both Sir William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. The English captured him in June 1306. Suffering the same fate as Wallace, a year later Fraser was hung, drawn, and quartered. His head was impaled on a spike and displayed next to his comrades on London Bridge. Almondell and the surrounding environs were once in possession of David Stewart Erskine, the 11th Earl of Buchan, and his wife Margaret Fraser. Erskine, the founder of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, was enthralled with anything to do with the Scottish knight Sir William Wallace. So much so, he erected this memorial to his wife's descendant, as well as the Wallace Statue near Dryburgh. The second stone, also funded by Erskine, is located some distance away and can be found along the road leading out of the estate. Hidden among the underbrush, on the right-hand side of the road, a few yards from the Drumshoreland crossroads. This carved tablet may well be the earliest surviving memorial to Wallace in Scotland. The Latin inscription reads: M.S. GUL VALLAS OCTOB XV MDCCLXXXIV Basically translated: Sacred to the memory of William Wallace October 15, 1784. This is the same year carved into the previous stone. The placement of this stone indicates the area Wallace and his men would have patrolled, keeping an eye on King Edward II and his army, just before the Battle of Falkirk in July 1298.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/william-wallace-marker

0 notes

Text

UK, Aydon Castle in Northumberland is a fortified 13th century manor house sitting in a naturally defensive position high above a river and not too far from the town of Corbridge. It is well intact and preserved building assemblage and one the finest and most unaltered examples of a 13th century English manor house. It was originally built in 1296 as an undefended residence by a rich Suffolk merchant named Robert de Reymes and replaced an older timber building on the site, it was soon fortified following the outbreak of the Scottish Wars of Independence and increased raids into Northumberland by the border reivers. Aydon was pillaged and burnt by the Scots in 1315 and sustained a fair bit of damage, it was further damaged two years later in 1317 by English raiders seeking to loot whatever the Scots had left. Robert de Raymes is known to have fought at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298 and was captured at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. He was ransomed and between this and the destruction of his estate at Aydon he was left financially ruined. By the 15th century his descendants had been forced to sell the estate and it changed hands a number of times, though remained little changed until the 17th century when it was used as a farm house until 1966. The castle remains historically significant due to the minimal changes and its basic structure, layout and medieval features being retained, including a solar with original fireplace, grand hall, garderobe (latrine block) and crenellated parapet with arrow slits. Today Aydon Castle is a ‘Schedule Ancient Monument’ and Grade I listed, currently owned and operated by English Heritage.

0 notes