Text

Salvator Mundi - master of the dead eyes

Salvator Mundi, various attributions (Louvre Abu Dhabi)

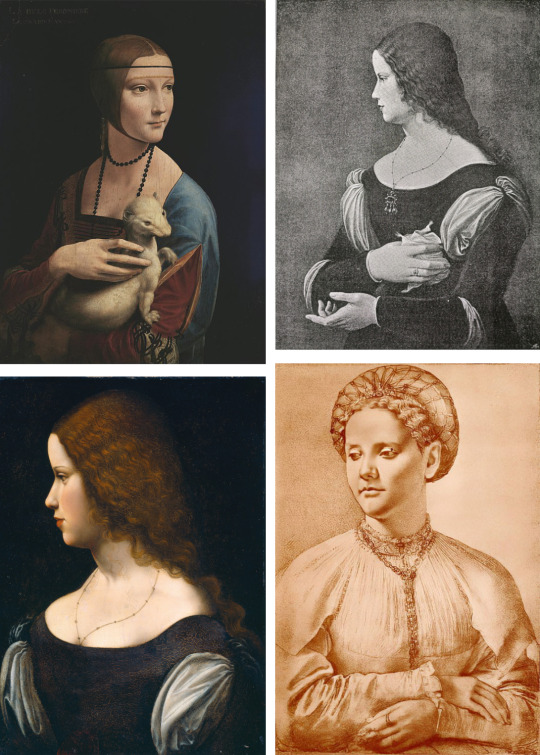

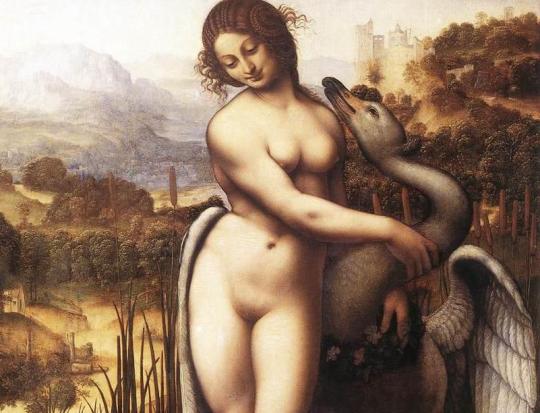

The Salvator Mundi painting, widely touted as a Leonardo, seems to have disappeared into the limbo of the Saudi Royal family’s treasury where it will doubtless lie, like an ingot of gold in a vault, unseen by most and unappreciated by its owner except as proof of the great wealth required to secure it. Frequent mention, however, is still made of this picture, and while that continues, so does the undesirable confusion that is spread by any demonstrable misattribution. This Brief Study is intended to provide that demonstration.

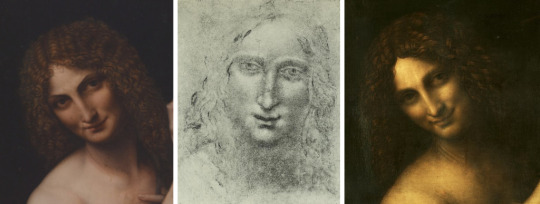

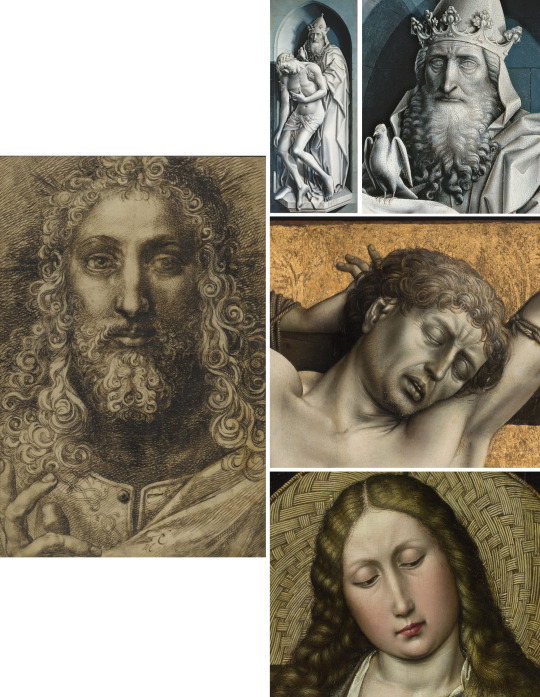

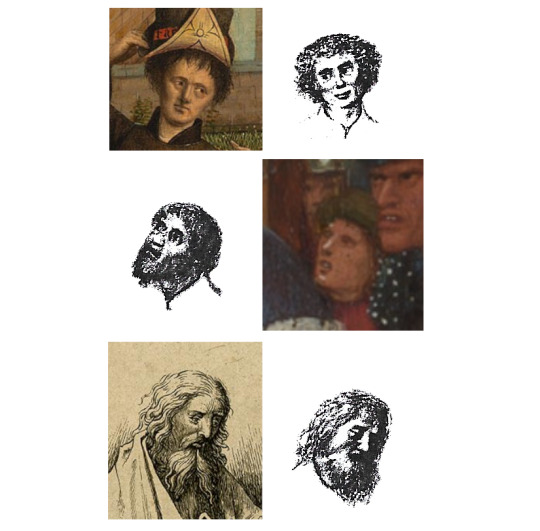

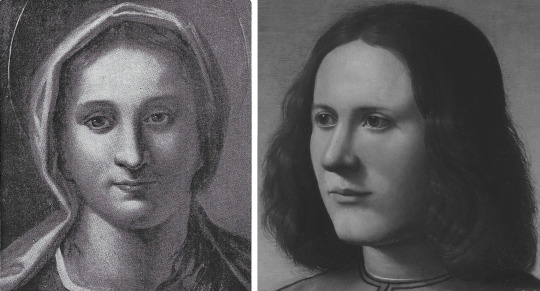

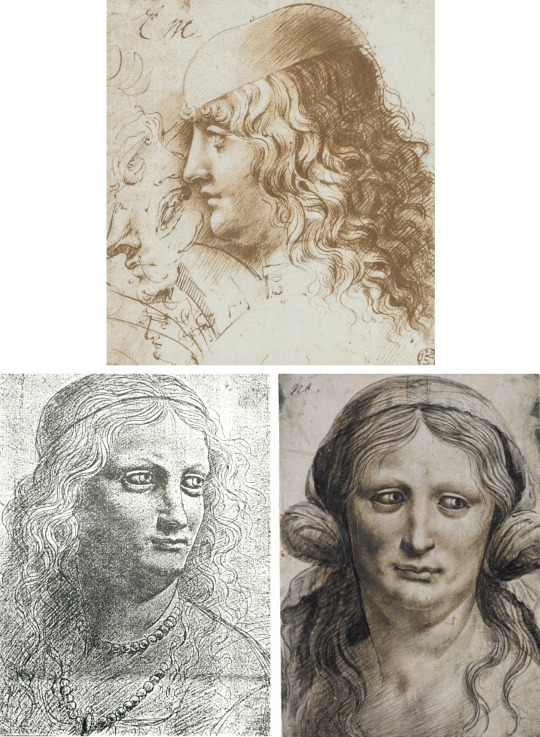

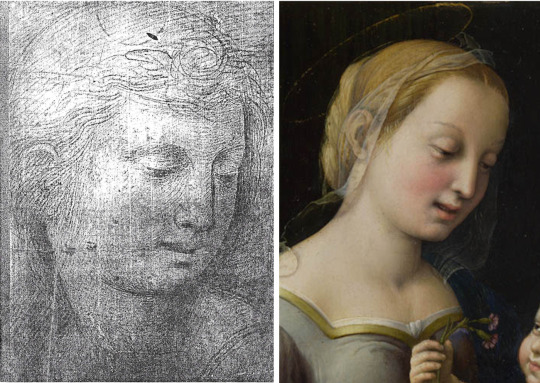

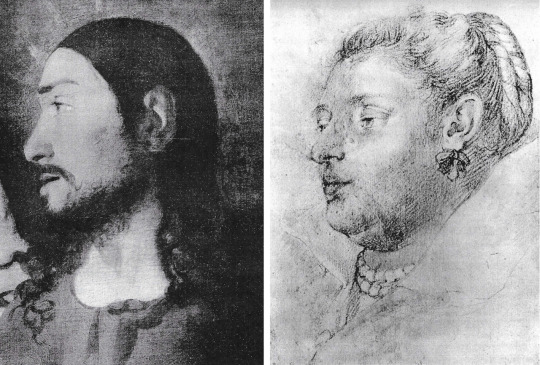

From left: Head of the Young John the Baptist (Drawing from a private collection, featured in an auction catalogue from 1934 as ‘School of Leonardo’) ; Salvator Mundi ; Head of a Woman (Musee du Louvre?)

Drawings, as always, are helpful. Here are two, to set beside the Salvator Mundi: on the left of it a drawing of a young John the Baptist, on the right a drawing of a young woman, possibly at the Louvre. It is enough to compare, and find similar, the eyes, the nose, the mouth, the treatment of hair. If likeness means anything, it ought to obtain in a juxtaposition such as this. As soon as it becomes clear that these two images are products of the same hand, it becomes clear also that the artist who made the drawing cannot be Leonardo, who never drew like this, and therefore Leonardo cannot be responsible for the painting either.

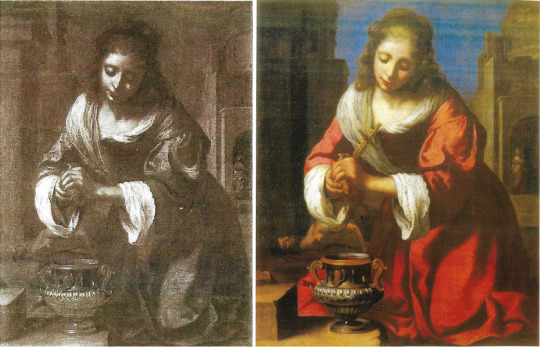

Of course the Salvator Mundi is Leonardesque. It is by an inferior artist (perhaps Salai, as once suggested by Suida) who has latched onto the ‘sfumato’, or smoky mysteriousness, that is displayed – for some tastes, to excess – in the late Leonardo Saint John the Baptist at the Louvre and copied by this artist in a painting at the Walters Museum. This mysteriousness, the smoky atmosphere implied in the etymology of the Italian word, is indulged in by this artist as if it was all that mattered in Leonardo’s art. The result is that Christ stares out at us, like a ghost from another world, with those strange, ‘dead’ eyes.

Left: St John the Baptist by the follower of Leonardo – Walters Museum, Baltimore ; right: Leonardo’s original – Musée du Louvre

Comparing the earlier drawing with the two paintings of John the Baptist

Comparing the earlier drawing with the two Baptist images either side, one by the copyist, the other by Leonardo, reveals as much as the difference in colour, the ‘Salvator’ eyes, nose and mouth.

Both attributed to the School of Leonardo, Left: ‘Head of a Youth’ – Ambrosiana, Milan ; Right: Portrait of a Lady – Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina)

Another drawing , of an androgynous-looking youth at the Ambrosiana, shows the same rather long eyes whose lids are more prominent than anything between them . This might almost be a study for the no less ghostly Portrait of a Lady at Columbia Museum of Art in South Carolina. The same artist’s draughtsmanship (or lack of it) is seen in a drawing (Mona Vanna) and a painting both featuring a naked Mona Lisa. A weak sense of form is disguised by a quantity of perfunctory smudging of charcoal or graphite. His admiration for Leonardo is matched by his failure to understand how necessary a proper grounding in observational drawing was to Leonardo’s painted work. A similar failure attended the followers of Turner.

Left: Mona Vanna, attributed to Leonardo ; Right: Female Figure, attributed to Salai

If we return to the Salvator Mundi, we can observe the unconvincing treatment of drapery folds and the way in which ornamented braidwork is not adequately integrated with the rest of Christ’s robe, but lies across it in two, rather than three, dimensions. When our eye moves to the orb, it is equally dissatisfied by the lazy depiction of it, with no attempt at highlight. The orb is as dead as the eyes.

The draperies, braidwork and orb from Salvator Mundi tell us this is not Leonardo’s work

Colour is always a significant indicator in paintings. In this case we have a near-Prussian blue with chestnut browns trailing off into a deeper brown penumbra. This is the palette of the Lansdowne Madonna (‘Madonna of the Yardwinder’), a more impressive work than the Salvator Mundi but displaying a similar tendency to wrap figures in a haze of sfumato.

Left: The Lansdowne Madonna – Private Collection – features the same colour palette and ‘sfumato’ as the Salvator Mundi

Clearly I do not hold this artist in much esteem. Plutocrats are welcome to spend a fortune on his work, but the rest of us should keep our eyes peeled for quality and not allow our vision to be blurred by the ‘Leonardo mystique’ and the floaters of dubious attributions. What this case highlights, not for the first time, is the regrettable necessity for connoisseurs to apply themselves to mediocrities. In an ideal world they would not need to, but they often have to because one person – an originator whom others follow – has ascribed a work by an inferior artist to a vastly superior one. These words, inferior, superior, imply what is at stake: a difference of quality. The exercise I have conducted here will have some value if it succeeds in demonstrating that difference. A painter who has little sense of form cannot disguise the fact, try as he may, with ‘mystery’ that has no depth or substance; it is hollow and spectral, like the dead eyes. If we cannot definitely name him, let us nickname him the Master of the Dead Eyes.

#leonardo#leonardo da vinci#salvator mundi#connoisseurship#studies in connoisseurship#art history#attribution#painting#louvre

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rogier and Campin: Mistaken Identities

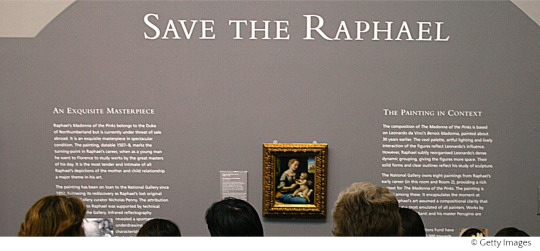

Connoisseurship, by its nature, will often involve mistaken identity, work by one artist being taken for that of another. This Study looks at a case that can be illustrated by work attributable to two famous fifteenth centruy artists, Rogier van der Weyden and Robert Campin, within one collection, that of the London National Gallery, and the relation of these pictures to others elsewhere.

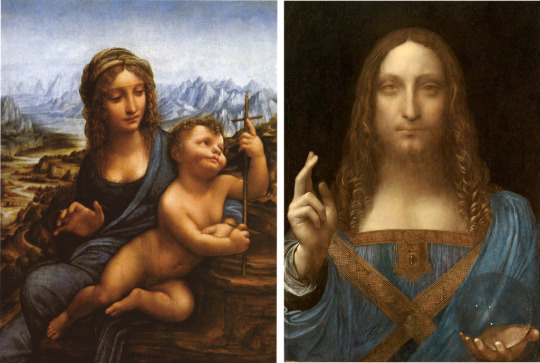

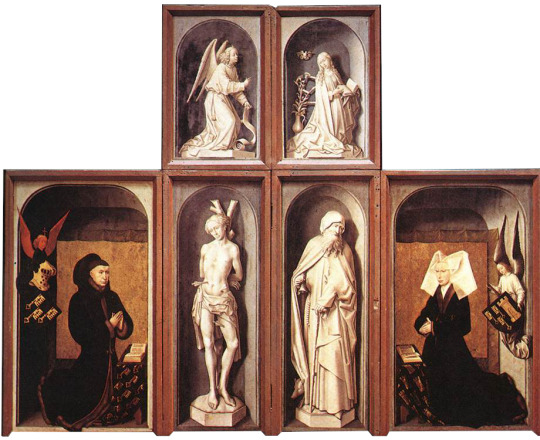

When juxtaposed, it is easy to see the similarities between faces in Rogier's Altarpiece at Beaune and portraits in the National Gallery, attributed to Campin. Such a degree of likeness makes it hard to see how there could be disagreement that they were all painted by the same hand. Stylistically, everything corresponds, even the craquelure

In the above juxtaposition, the left-hand face of each pair is a face out of the Beaune Altarpiece, the Last Judgment, still at Beaune in Burgundy, that everyone seems agreed is the work of Rogier van der Weyden. The right-hand face of each pair is of the Man and Woman, respectively, portrayed in two separate panels at the London National Gallery where they are ascribed, not to Rogier, but to Robert Campin. The two artists were famous in their day for the outstanding quality of their work, and they both presided over large workshops.

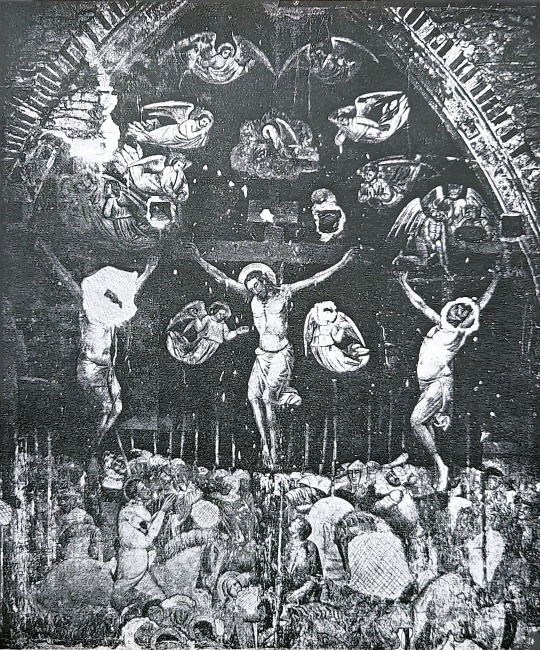

The Altarpiece at the Hotel-Dieu, Beaune. Open, it shows The Last Judgement

Closed, the polyptych shows the donors kneeling before statues of saints

Here is another Portrait of a Man that can also be seen at the National Gallery. It is the portrait of a known person, Alexander Mornauer.

Portrait of Alexander Mornauer, attributed to "the Master of the Mornauer portrait", National Gallery, London

The Mornauer portrait before cleaning, showing a 'Holbein blue background, and reworking of the hat

He was given a plain blue ‘Holbein’ background that has been removed, as being a later addition, to reveal one that is of much more interesting texture and of a sort of puce colour. The painter of this picture is simply called ‘The Master of the Mornauer Portrait’, thought to be from ‘South Germany’.

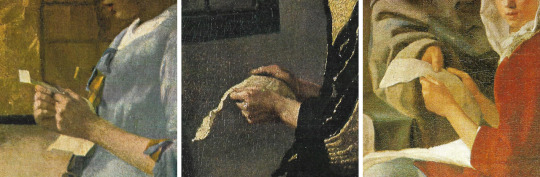

If we now place this Mornauer portrait between two other images, the Portrait of a Stout Man from the Thyssen Collection in Madrid (ascribed to Robert Campin) and the two onlookers beside the Bad Thief to the Left of Christ from the panel at Frankfurt (Staedel Institut), generally considered a work by Campin, do we not see similarities, in this second case, nearly as compelling as the very different similarities in the first?

Left to Right: The Mornauer Portrait; Portrait of a Stout Man, attrib. Campin, Museo Thyssen, Madrid; detail and full image of The Bad Thief to the Left of Christ, attrib. Campin, Staedel Museum, Frankfurt

The Mornauer portrait clearly predates both the Thyssen Head of a Man and the Frankfurt Crucifixion, which one takes to be late work by the artist; that said, we can see an earlier manifestation of the same extraordinarily bold facial modelling, the same eyes and eyebrows, the same fine brushwork in the brown hair and the hairs of fur, and, in the detail of the two onlookers to the Crucifixion, very similar and distinctive hands displaying all their veins and joint-creases.

Much work remains to be done on the oeuvres of two men who were clearly the stars of the generation after the Van Eycks, but what these comparisons already suggest is that their styles are very distinct from each other. It appears that two portraits have got linked with Robert Campin when they are much more likely to be by Rogier van der Weyden, and a fine work by Campin in the same Gallery has gone unrecognised, relegated to ‘South Germany’. There is evidence here of the muddle that surrounds these two names.

I do not believe that we have many works anywhere by Robert Campin, but what there is strikes me as of remarkably high quality. His hyper-realism may not appeal to all tastes today, but it belongs to its time and makes a superlative link between Jan van Eyck and Dürer in the tradition that leads on to Holbein, and eventually Ingres. Of work by Rogier van der Weyden we have more, including two masterpieces, the Beaune Altarpiece and the Madrid Deposition, but his work likewise has to be distinguished from that of numerous artists of his time, mostly of lesser talent, who spent their careers in workshops such as those headed by himself and Campin.

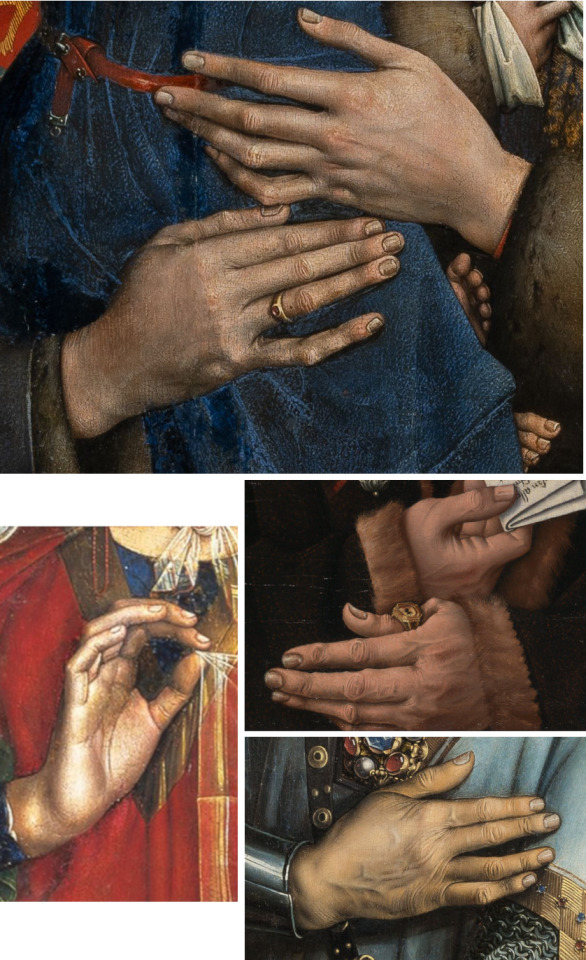

Left to RIght: The Mornauer Portrait; Portrait of a Man, attributed to the same artist, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin; in BW; Reflectogram of the Mornauer Portrait, revealing the same style of folds in the clothing and vein details in the hands

I wish to draw attention at this point to two drawings. The first is a portrait of a man of middle age with black curly hair, wearing a hat and holding his hands together with the two thumbs abutted. This remarkable image is held at the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin and attributed to the same hand as the Mornauer. The penmanship in the modelling of the man’s shirt is superlative and the vividness of his presence is all the greater for the addition of watercolour to his face, neck and hands.

The connection, as I see it, with Campin is made by a very helpful infrared reflectogram of the Mornauer portrait in a publication (2010) by the National Gallery, entitled A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries. The underdrawing of that painting is so close to the treatment of the folds in the sleeves of the shirt in the drawing that I think it very likely that they are by the same artist. Note the veins in the hands of both painting and drawing; Dürer could not have observed them better.

Left: 'Le Christ Bénissant', attrib. Toussaint Dubreuil, the Louvre; Right from Top: Detail from Campin's Throne of Mercy; Detail from Campin's Bad Thief; Detail from Campin's Madonna by a Firescreen, National Gallery, London

The second drawing - an image at the Louvre entitled Christ Blessing - I also think is by Campin, though probably from a different period of his career. Here the penmanship is bolder and looser than in the drawing just mentioned, but the dense cross-hatching and other mark-making is very similar. Below are some juxtapositions that help to link this drawing with the Mornauer portrait and other Campins in the treatment of facial features, hands and hair-curls.

Left to Right: Faces of Mornauer; Christ; the Stout Man

Hair and fingers from the Bad Thief (left) and Christ Bénissant (right)

Hand details: VIrgin and Child, Campin (top); Saint Veronica, Campin (left) both Staedl Museum, Frankfurt; The Mornauer (middle); The Bad Thief (bottom)

That two paintings by Rogier van der Weyden can be taken for work by Campin when the two artists are so completely different is concerning. The focus of the present Study has been limited to three paintings in the London National Gallery, the stylistic connection of two of them, the paired portraits of A Man and A Woman, with Rogier’s Beaune Altarpiece, and a third, the Mornauer Portrait, with Crucifixion and other panels at Frankfurt. On the evidence even of these few works we can see Campin as a master capable of projecting a very powerful image with hyper-realistic attention to texture and fine detail. The Rogier portraits are realistic too, but less forceful and arguably more sympathetic depictions of individuals with faces easily associated as those of husband and wife.

Clearly there is scope for a wider discussion of the oeuvres of these two very important painters. I hope a future Study can attempt to address that much more complex issue

#campin#rogier#rogier van der weyden#beaune#Dutch Painter#painting#connoisseur#connoisseurship#studies in connoisseurship#art history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vermeer : A Postscript

In the text of my Study in this series that is about Vermeer I include a reproduction of a now lost picture of a servant clutching a letter as she looks down towards a child holding a bowl. If that work was a Vermeer, I wondered why there are no surviving ones that contain young children. The house he shared with his wife, Catharina, was full of them at different times. I speculated that perhaps it was because they were so lively and never still; the girls would become suitable models when they were young women.

I now wish to put forward a further possible Vermeer. It is a sad image of a young girl who is certainly still because she is on her death bed.

This poignant, tender and very beautiful picture is at the Musee des Beaux Arts at Besançon in France, where it hangs unattributed as a Portrait of a Dead Child, Flemish from the 17th century. Obviously it is a very personal painting, the work of a grieving parent. The artist brings us to the very edge of the bed where his child lies. Her eyes are nearly closed, the shape of them like the eyes of the boy in a drawing, below, at Berlin. Her hair is a pale flaxen colour, a lighter version of the yellow so often used by Vermeer, in the Lacemaker, for example, or the Girl with a Pearl Earring. There is a slight halo around her head. The folds of pillow and coverlet have a ghostly pallor, soft and unfocussed, like a mantle of snow. Most remarkable of all is the absence of ordinary daylight, the same absence one finds in Vermeer’s Servant asleep at a Table (at the New York Metropolitan Museum), except that the servant is merely asleep, but the child is gone into the darkness above her bloodless face, ashen now like the bedsheet. Under that sheet is a deep red blanket forming a triangle in the lower right corner of the picture.

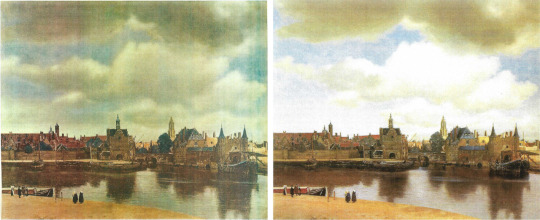

It is the particular red of this blanket that alerts me to the possibility that the picture is a Vermeer. There are pictures by him that have no red in them at all, but this red, in deeper and lighter shades, is nevertheless a feature of his palette that recurs quite often. It is the red, for example, that we find in the jacket of the girl reading a score in The Girl Interrupted at Her Music at the Frick Collection in New York, and again in the Girl Drinking with a Gentleman, at Berlin. It is the colour of the roof tiles in The View of Delft, at the Mauritshuis, and of the skirt of the woman with her back to us, who stands at the virginals in the Royal Collection’s Music Lesson. Somewhat lighter, it is the red of the woman’s satin dress in the Couple with a Wine Glass, at Brunswick, and in two early works, the Edinburgh Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (where Mary wears it) and in the Dresden Procuress, in the jerkin of the man who fondles her breast. At Besançon the colour is deep and it speaks to us differently: in the presence of death it is an assertion, and reminder, of life, and life blood.

The comparisons made below, between the Besançon Dead Child, focus on two aspects of the former, the red of the blanket and the brownish background. Clearly the colours in reproductions vary in their fidelity to those in the originals; so, if there is merit in my attribution to Vermeer, it behoves those more acquainted with the originals, such as the curators of the current Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, to make their judgement accordingly. The hue of a red, or any colour, may be deeper or lighter. My argument relies on the red in question being essentially the same as what we find in his pictures, only in differing strengths. The colour of walls in Vermeer shows wonderful variations according to the degree of light falling on them. At Besançon there is, appropriately, a very subdued, ‘dead’ light, not the lively one that enters through a window.

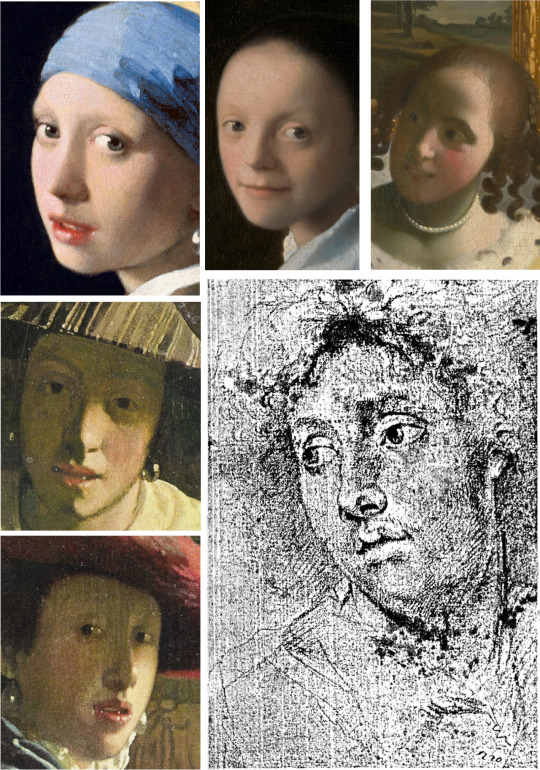

Clockwise from Top Left: View of Delft (Mauritshuis); Portrait of a Dead Child (Musee des Beaux Arts, Besançon); The Wine Glass (Gemäldergallerie Berlin); At the Procuress (Staatlichekunstsammlungen Dresden); Girl Interrupted at her Music; Officer and the Laughing Girl (Frick Collection)

Clockwise from top left: The Geographer (Städel Museum Frankfurt); Portrait of a Dead Child; Girl Reading a Letter (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden); Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (National Gallery London); At the Procuress; Centre: Study of a Boy’s Head (Berlin Printroom)

As for the identity of the child, if this is indeed a Vermeer she must be one of the four daughters born before a son arrived in 1654; the approximate date of the picture, ‘circa 1650’, suggested by the Besançon Museum is therefore a reasonable guess.

The craquelure, it may be added, is also compatible with an attribution to Vermeer. The painting is on canvas and rather larger than one might expect (58 x 47.5 cm) for so intimate a scene.

I should add, by way of a concession to sceptics, that the argument here is not an easy one to make, because the very restricted content of the picture offers little with which to build it; around the head of the child only bedclothes and a blank wall. A blank wall by Vermeer is nevertheless different from a blank wall by Nicholas Maes or Pieter de Hooch.The case for attribution to Vermeer rests on features described above, and I hope they are enough when taken with what seems to be the case, that no other attribution has been suggested within mid-seventeenth century Netherlands that meets the obvious quality of this work.

The description just made, of the background in the picture as a ‘blank wall’ is not really correct; it is not a background, nor is it a wall, but rather an overtaking nothingness, the visual representation of absence and loss. Because Vermeer and his wife were fecund and had many children does not mean that the loss of any one of them was not a very sad occasion which he, as a painter, might well have wished to mark. If this painting is by him, as I am inclined to think, then it is further evidence that family was at the centre of his art, as of his life. He painted and celebrated the visible, the world of living light and shadow; sleep and death remove us from it, but what the sleeping servant and the dead child cannot see is still there to be seen and to be witnessed, albeit in a manner appropriate to those states, in a ‘dying of the light’.

#vermeer#lost paintings#dutch painter#painting#art history#studies in connoisseurship#connoisseurship

1 note

·

View note

Text

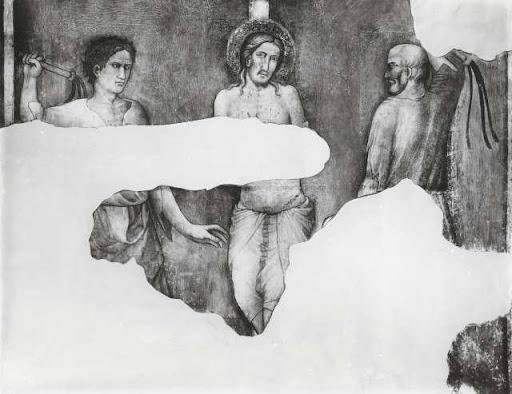

Hidden by Masolino

School photos, those wide-angle records of all the staff and pupils in a year, sometimes include a child who is partly concealed by another and consequently harder to identify. Similarly, in the long conspectus of artists at a given time, there are places where one partly conceals another. The collegiate church at Castiglione d’Olona, to the north-west of Milan, is such a place. To Renaissance specialists it is well known for having been frescoed in the 1430s by Masolino, the painter who had earlier worked alongside Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel of the Carmine church at Florence. However, there was another artist decorating the walls at Castiglione d’Olona. I doubt that anyone knows his name, but I will devote this Shorter Notice to bringing him out from behind Masolino because I think he was the better artist and certainly the more modern in the context of his time.

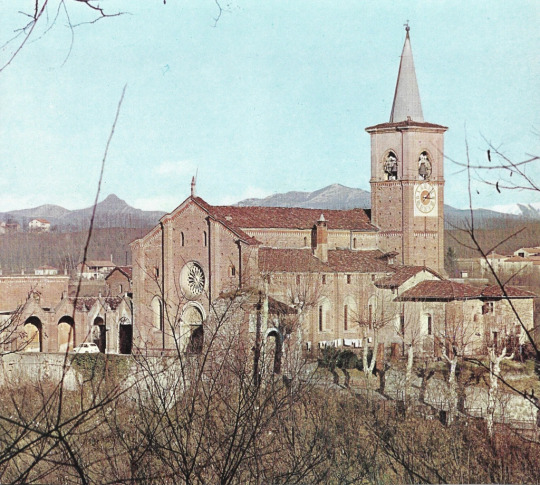

Collegiate Church at Castiglione Olona, Lombardy, Italy

As I have said in my Studies on Masaccio, Masolino was in many ways a late Medieval artist trying to adapt to the new art that was sweeping through Florence in the latter part of his career. This other artist is no Masaccio, but he seems much more confident of his powers within that developing trend. He was also the creator of a rather memorable cast of characters rendered on stage in painted scenes and studied close-up in beautiful line drawings. I regret that I do not possess enough images to adequately represent his work at Castiglione d’Olona – a consequence of Masolino hogging the attention of scholars and therefore publishers and photographers – but there are enough to at least make clear that the artist he eclipses is worth looking at.

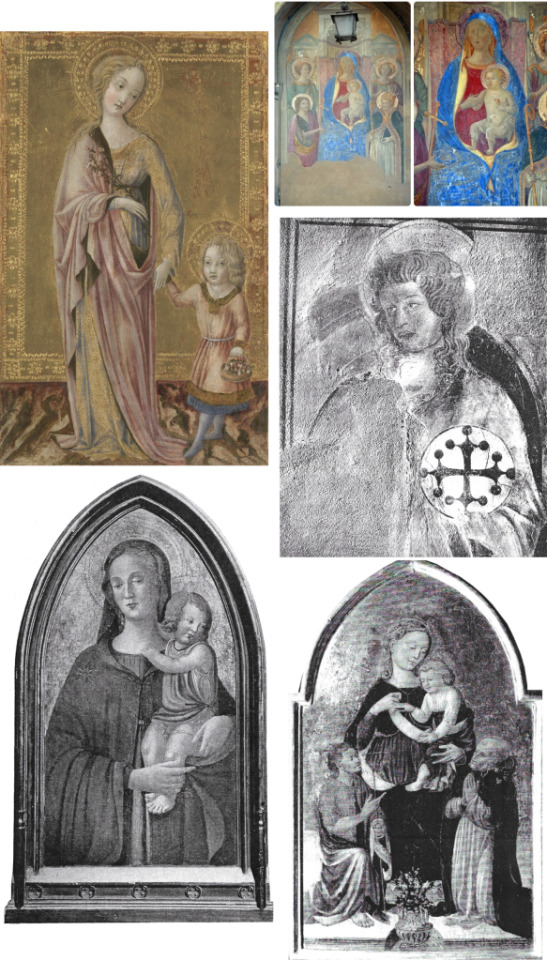

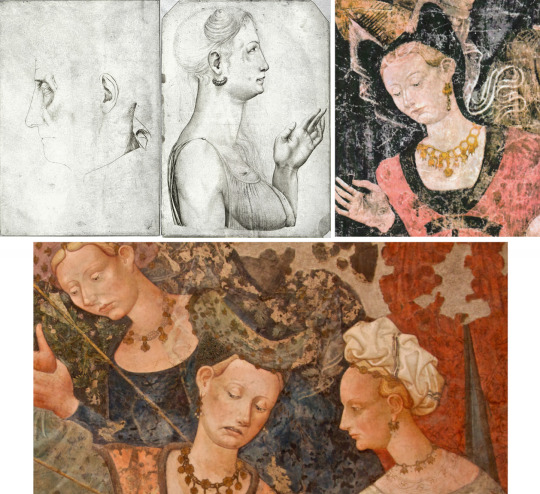

Frescoes on the ceiling at Castiglione d’Olona, Above: the more colourful of which are by Masolino and, Below: Monochrome images of the lower frescoes, which were painted by this other artist

The principal scenes are from the life of two early Christian martyrs, Saint Stephen who died in the First Century, and Saint Lawrence, martyred at Rome in 258. We can begin with the Trial (disputa) of Saint Stephen, a scene in which the Saint, looking to our right, stands like a preacher in a pulpit, but a pulpit that, as he was denounced by Jews as a blasphemer and had to defend himself, is also a dock. To left and right of him are his denouncers. Behind him we see an arcaded church interior, the columns given leafy capitals.

The scene is poorly preserved, but one feature of it is still clear, and that is the artist’s draughtsmanship, his drawing with a brush. This sets him apart from Masolino: drapery folds in Masolino are not represented as lines, but they very clearly are in this and all the other scenes depicted by the artist we are considering.

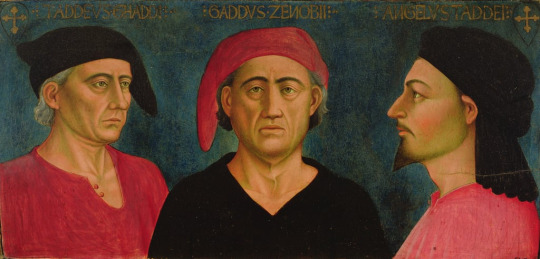

Left to Right: Tuscan Man, Albertina Museum, Vienna ; Head of a Man (attrib Uccello), Ashmolean Musuem, Oxford ; Man in Profile (attrib Uccello) Louvre, Paris

Fortunately there are drawings plausibly by him which attest to his skill as a draughtsman. Four are at the Albertina in Vienna, one is at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, another in the Louvre. One of the four at Vienna is a portrait of the Prior of a Florentine church, SS Michele e Gaetano. Interestingly, the head, drawn in pen and ink, has a brownish wash and is set against a backdrop described as ‘shaded with red chalk’. All have remained assignable only to the ‘Tuscan School. first half of the fifteenth century’, but I want to assign them to this artist. With a delicate but assured hand he draws the profiles of men with aquiline noses, ‘crows’foot’ creases about the eye, incisive lips and jutting chins The Oxford one is partly colour-washed, but not in a way that detracts from the linear elegance and purity of the image.It should be compared with the profile of the Emperor Decius pointing his accusing finger at Saint Lawrence.

Left to Right: Portrait of a Young Man (attrib Uccello) Musée des Beaux-Arts, Chambéry ; Head of a Man, Albertina, Vienna ; Young Man in a Scarlet Turban (attrib Masaccio), Isabella Gardner Museum, Boston

At the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Chambéry in France is a profile portrait of a Young Man, attributed by some to Uccello, by others to Masaccio. This also I want to claim for our artist. It has his linear clarity all over it ( perhaps a little too markedly in the eyebrows), and that purity of line is manifest in a drawing in the Albertina at Vienna which may not be a study for the Chambéry painting, or even be of the same young man, but definitely exhibits the style and demonstrates, I suggest, a refinement of sensibility the more evident when the painting is juxtaposed with a similar painted portrait from the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston, quite likely Masolino’s work but in any case careless and clumsy by comparison.

Left: Madonna of Humility, Alte Pinakothek, Munich and Right: Madonna and Child, Kunsthalle, Bremen (both attrib Masolino)

A second characteristic of the Chambéry picture is its palette. This has a nut-brown, autumnal warmth to it which we can pick up on elsewhere, for instance in the Madonna and Child at the Alte Pinakothek at Munich where a similar tawny gold appears in the dress of the Virgin under her blue robe. This very attractive painting has often been assigned to Masolino, but juxtapose it with Masolino’s Bremen Madonna (at the Kunsthalle in Bremen) and it is clear that a quite different hand is at work – the hand, I am sure, that is responsible for the Chambéry and other pictures we are considering.The lack of colour reproductions of our artist’s work at Castiglione d’Olona is regrettable, but beneath one that shows Masolino’s Nativity we catch the top of the Saint Lawrence before the Emperor Decius and can see at once how much deeper and browner the palette is, when compared with Masolino’s pastel one of pale yellows and pinks.

In this image from Castiglione d’Olona we can see a change in colour palette between the upper frescoes and those below

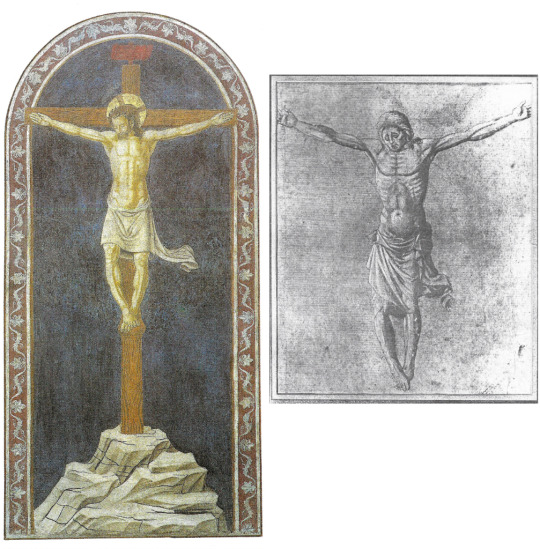

On the subject of the brown palette, there is a fresco in Santa Maria Maggiore in Florence of Christ alone on the Cross; here the figure of Christ is modelled in pale brown, the Cross is brown (with a darker brown grain), the plain background is dark blue over brown, and the decorative border, arched at the top, is white over brown. A fine drawing for a crucified Christ (ex Coll. N. Colville, whereabouts unknown) appears to be a study for something similar.

Left: Fresco at Santa Maggiore, Florence and Right: drawing, possibly a study for a similar fresco, whereabouts unknown

That same nut-brown colour of the Chambéry picture recurs in the background of a Madonna and Child flanked by two Angels in the Augustinian church of Santo Stefano at Empoli. The angels with their multicoloured wings are sisters, as it were, to those of the Madonna at Munich. The blue robe of the Madonna in the latter work falls like a cascade of water from the hood round Her face down into more and more complicated folds that are lovely to look at but leave one wondering where Her right knee and leg actually are.The rhythms here are essentially Gothic, as in , say, Gentile da Fabriano.At Empoli the artist has moved forward from such Gothic indulgence and the forms are more solid and suggestive of a later date.

Madonna and Child with two Angels, Augustinian church of Santo Stefano, Empoli

Three works that perhaps antedate the Munich picture are a damaged, much-weathered tabernacle in Piazza Santa Maria Novella in Florence – another Mother and Child, with four Saints – a fresco fragment of an Apostle from Santa Maria del Carmine in Morrocco, Italy, and the delightful picture in the London National Gallery of Saint Dorothy holding the hand of a boy Christ. The complication in the drapery of Dorothy’s outer robe is reminiscent of what we find in the Munich Madonna. Close in style is a panel of unknown whereabouts showing Mary enthroned with the Child holding a scroll, the two of them flanked by John the Baptist and another Saint, with a vase of flowers between them By contrast all is more straightforward and more solid in yet another Madonna and Child that was sold by Drouot in Paris in 1927.

Clockwise from Top Left: St Dorothy, National Gallery, London ; Tabernacle in Piazza Santa Maria Novella, Florence ; Frescoe fragment, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence ; Two panels of unknown origin depicting the Madonna

One more Mother and Child picture, a Madonna of Humility at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, belongs somewhere in the series, but it is, apparently, both unfinished and much altered.The artist’s linear delicacy, in treatment of hair and drapery folds, is eloquent in spite of the condition and strange colouring.

Madonna of Humility, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

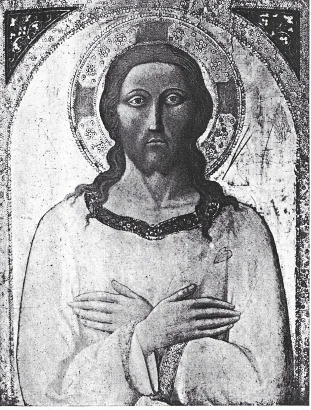

All the above items – illustrations 15 to 21- can be taken to represent, in respect of Castiglione d’Olona, an earlier, Florentine phase of the artist’s career. We can begin to move it on by considering first a Figure of Christ with hands crossed over His breast, now at Minneapolis. This has much in common with the Munich Madonna but the modelling of Christ’s face links it also to an unusual panel in the Uffizi that memorialises three painters of the Gaddi family, Taddeo, Zenobi and Angelo.The profiled head of Angelo, on our right, is a strong reminder of the Chambery Portrait of a Young Man, the associated Albertina drawing, and some of the young male heads in the fresco scenes at Castiglione d’Olona. One begins to recognise the type: clear eyebrows, a sharpish nose, tightly closed lips, and a definite chin. This is what we find also in the Ashmolean and Vienna drawings mentioned earlier.

Facial features in a portrait of Christ, above, are reminiscent of those found in a protrait of the Gaddi family at the Uffizi Gallery, Florece, below

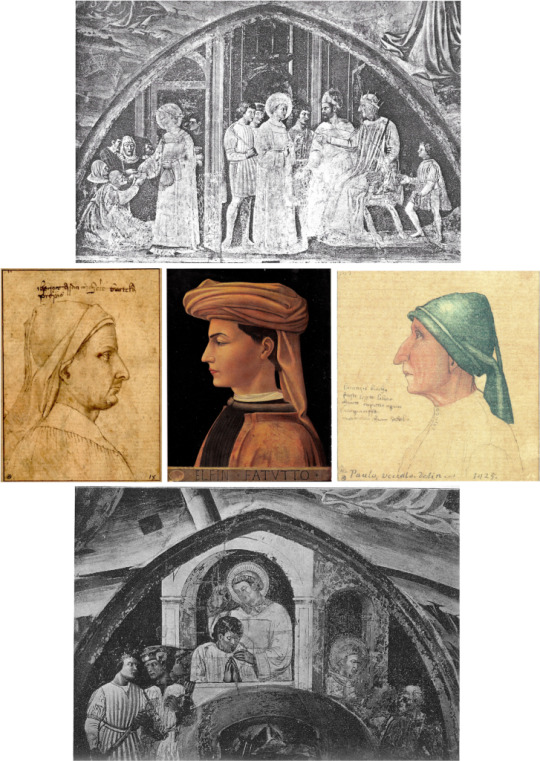

Top and Bottom: Frescoes from Castiglione d’Olona ; Centre from Left: Tuscan Man, Portrait of a Young Man, Head of a Man, as before

To summarise: this artist, like Masolino, begins in the late Gothic style but appears throughout to be the better draughtsman, as evinced by the pure-line drawings and by the drawn nature of his work as both painter of panels and decorator in fresco. This superior competence allows him to delineate heads (often in profile) and whole figures with a sensitive precision and a sharper suggestion of character. Once seen, the Ashmolean Man with Aquiline Nose is not easily forgotten. I make no claims for the artist being any kind of undiscovered genius, but I find it pleasing if connoisseurship can bring out of the shadows someone whose work is worth reassembling in so far as that is possible, given the lottery of survival and the conflicted world of attribution. It remains to hope that some photographer will soon supply a better record, in colour, of the frescoes this nameless artist contributed to the decoration of the church at Castiglione d’Olona, and thereby give more prominence to one of the more interesting contemporaries of Masaccio in that early fifteenth century period of revolutionary change.

1 note

·

View note

Text

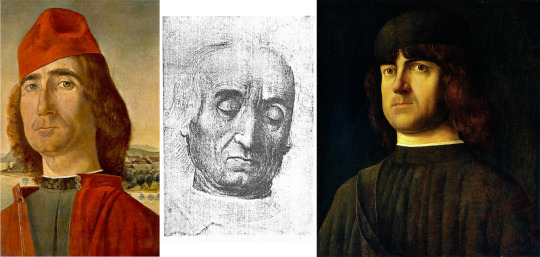

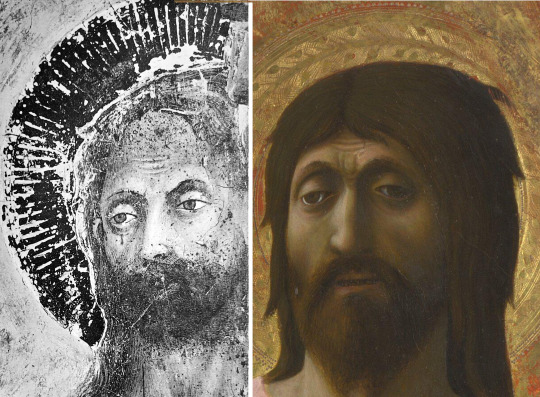

Hubert van Eyck

The boldest claim for connoisseurship is that it can sometimes resurrect an artist from the version of death that is oblivion or neglect. There is one outstanding example of this, outstanding in both senses, because the artist was no mediocrity but a pioneering genius. His name is Hubert van Eyck, the bachelor brother of Jan van Eyck. Hubert died in 1426, at what age is unknown.

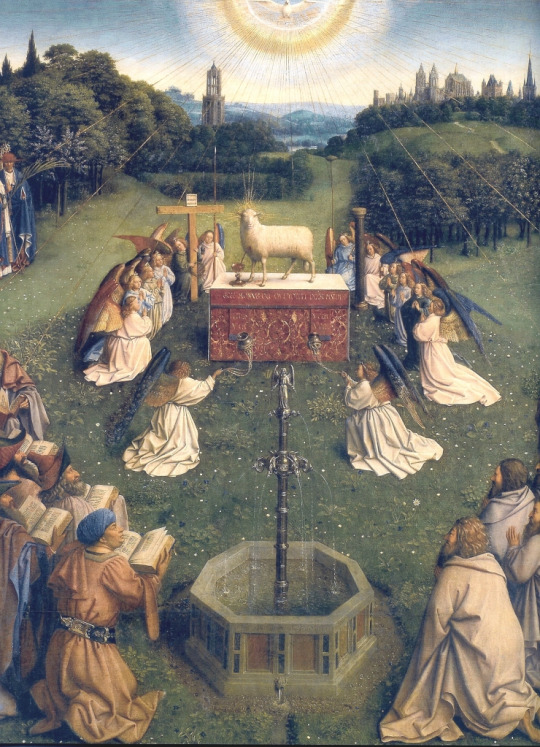

Apportioning work to Hubert and to Jan inevitably begins and ends with consideration of the famous Ghent Altarpiece, The Adoration of the Lamb, which was painted for St Bavo's Cathedral at Ghent and has remained there ever since, bar one stolen panel replaced with a replica.

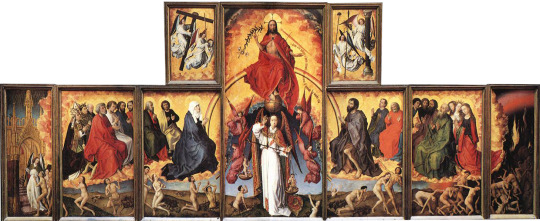

The Ghent Altarpiece, open (St Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium)

The altarpiece, closed view

The division of labour for the altarpiece’s many panels

Hubert’s story is one of posthumous eclipse: Jan’s work simply covers over and obliterates his brother’s. When eminent scholars have wondered if Hubert’s hand is even discernible in the Altarpiece, his very existence begins to be questioned. Jan’s work, meanwhile, becomes so extensive that one can scarcely believe it possible that so much meticulous, labour-intensive painting could be done in one lifetime by one man. Accepting, as I do, that Hubert did exist and did paint parts of that Altarpiece, I need to say at the outset that I find no particular difficulty in recognising which parts are his and which parts are Jan’s. I believe that Hubert painted all the lower panels of the opened Altarpiece and the four arched panels of it closed. The rest, for me, is Jan’s. Did he take over, and complete, what Hubert had begun?

As we shall see later, another difference between the brothers is that Jan cares about individuals; it is he who paints the portraits of the donors on the Altarpiece and has left us a handful of other painted portraits. Hubert includes many people in his work, but they belong to a repertoire of types, chosen and combined according to need. Survival involves much accident, but i am not sure that he has left us more than one independent portrait.

Hubert’s panels from the opened altarpiece, including the Adoration of the Lamb

Hubert’s panels from the closed altarpiece

There are different elements involved in this distribution and in the distinction drawn by it between two brothers who were both miniaturist in their technique but very different in other ways. Jan’s vision of the world was monumental in the sense that he could create grand figures that occupy a space sculpturally, but the space that they occupy is typically an indoor one This is often quite confined, but even where it is not - say in a church - it is of a kind to make a backdrop to figures which have a looming foreground presence. Such figures serenely dominate the space in a manner that is regal, befitting the Queen of Heaven, Angels, Saints, Sometimes, like real sculptures, they fill niches. By contrast, Hubert’s essential identity as an artist is that of a landscapist The space between him and the horizon is a need of his spirit; he does not want to be confined by walls or to see what delights him only through windows.

The Brothers in side-by-side – Hubert’s talent for creating small forms in big spaces, like the Adoration of the Lamb, stands in contrast to Jan’s preference for setting big forms in small spaces. Both of the above images feature cities in the background, but Jan has set his Annunciation in an enclosed space.

Virgin and Child – ‘The Ince Hall Madonna’ (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne)

Jan, then, is a chamber artist, like Vermeer. Take his early Madonna Enthroned, a small picture at Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria. The light visits her through the window and illuminates particularly a bit of wall to her right: this passage is pure Vermeer, two hundred years before he, too, immortalised the female presence in an indoor space lit from without. Already in the illuminations of the Turin Hours which I follow Kenneth Clark in giving mainly to Hubert - he is evincing a totally different take on the world, one that revels in a storm at sea, a calm lakeside, or the long line of a coast. He can make us feel the cold salt air and see the waves rolling in onto a low shore where a Duke and his entourage have landed and ride up the dunes on their way to his castle. Faced with painting figures in a room or a church, however, and one immediately senses that Hubert, at that stage, is less at ease, his discomposure evident in a relative lack of both atmosphere and compositional unity.

Miniature illustrations from the Turin Hours. Clockwise from top left: Agony in the Garden; The Cavalcade (destroyed); Baptism; Office of the Dead; Miracle of Sts Julian and Martha. All surviving works Palazzo Madama, Turin

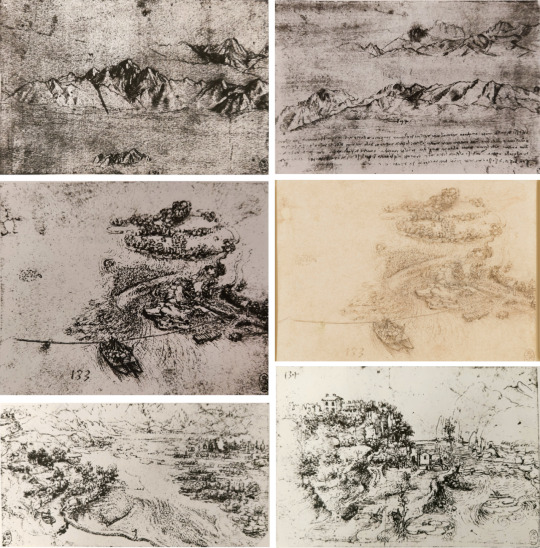

LANDSCAPE

The Crucifixion and The Last Judgement (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

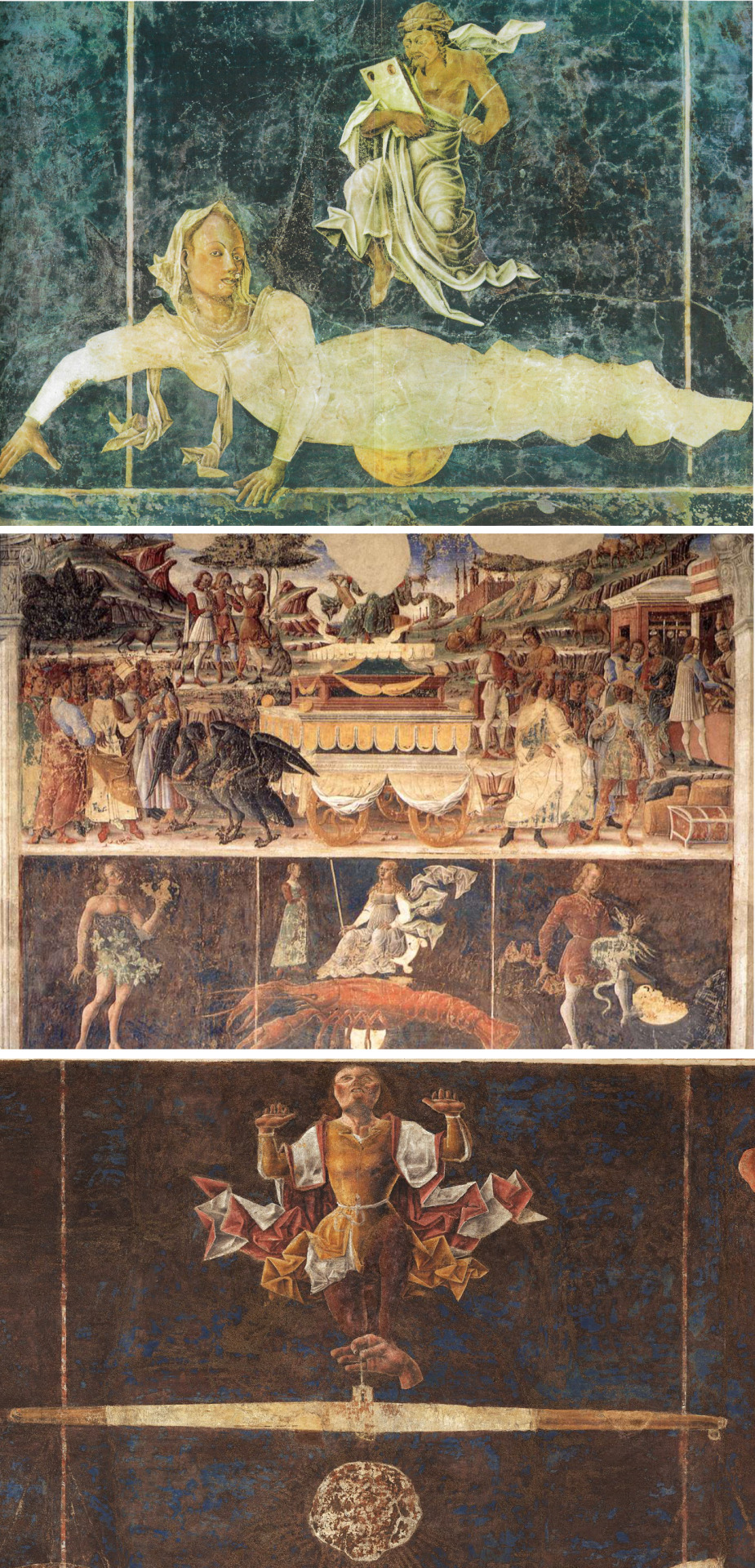

Further evidence of Hubert’s interest in landscape can be seen at the Metropolitan Museum in New York; here we find the Channel coast again, the rollers coming in onto long stretches of what are now Belgian beaches. The sea is a Prussian blue - a shade that Hubert particularly loves - with drowning souls in it pleading to be saved, like their luckier compatriots on land, from the horrors of Hell beneath. In the left-hand panel is an early version of a typical Hubert landscape: middle distance warmth of foothills and human habitation receding to a far range of blue mountains fading into blue sky, and all in clearest visibility (atmospheric sfumato still unborn). Both panels are crowded with people dead and alive, but the landscapes complement the crowdedness with an airiness and spatial largesse that is all-inclusive and ruffled only by some fretted cumulus and fretted waves. There are many colours, but they answer each other across the panels as might happen in a pair of stained-glass lancets. The correlations are not only chromatic but formal: the rising foothills of the left panel continue into the white lining of the Virgin’s blue robe in the right panel, and the darkness behind the arms of Death spread over into the left panel.

It is Hubert’s gift to give to crowded, jostling humanity so much space around it and so much air above it. As in the lake and coastal scenes of the Turin Hours there is conveyed to us the breathed atmosphere of a huge encompassing space that is beyond, yet all around, whatever is happening in the human world. He is very sensitive to this essentially calming influence of the natural world that is also, for him, a sacred one.

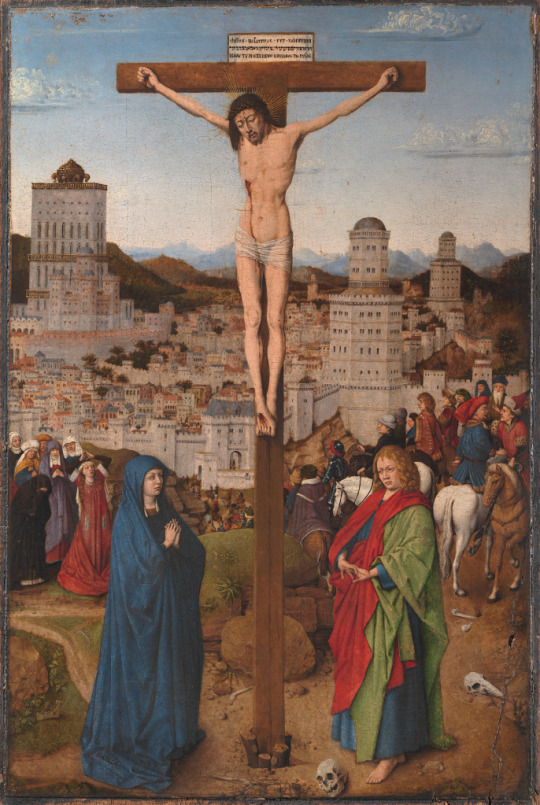

Christ on the Cross with the Virgin and Saint John ( Gemäldegalerie, Berlin)

In Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie there is a small Crucifixion with just Mary and John either side of Christ, she downcast and resigned, clasped hands out-turned, John turned away, weeping. The lovely landscape behind seems wintry, echoing the elegiac mood with a tall bare-branched tree; a city lies low amid uneven, intractable terrain, with a backdrop of remote mountains. Close up to the picture plane, the human scene is emotionally near, the viewer forming a fourth witness to a Passion whose outpouring is visible blood, invisible tears. The suffering, with that much haemorrhage, must be over, and the end is a resignation that makes a kind of peace with the larger world, shorn and naked now, but assured of resurrection. The picture illustrates perfectly Hubert’s ability to match landscape with human drama and emotion.

Crucifixion, National Museum of Poznan, Poland

In another Crucifixion, at National Museum in Poznan, Poland, crowded onlookers react in their different ways to the anguish on the Crosses. Again the landscape is important; no mountains, but a backdrop of partly wooded hills below a sky of scudding cumulus moving along with an event that is still unfolding, a Passion not yet spent.

Crucifixion, Ca d’Oro, Venice (attrib Hubert v Eyck or school of J v Eyck)

A late Crucifixion at the Ca d’ora in Venice shows the same out-turned hands we saw in Berlin, this time on John. This Crucifixion represents a substantial departure from earlier ones. Christ seems lifted high above Mary and John, while the city has come alarmingly close, a threatening source of crowds who are standing around, a little down from the hill of Golgotha. A group of women on the left look up at the back of Christ, while men on the right, on horseback, look in other directions as if the show they came to see is finally over. As for the city, it encourages Hubert to flights of architectural fantasy. Three structures of Babel-like height and mass tower over the huddled houses, more out of scale than even the real-life cathedrals were in Hubert’s day or the skyscrapers in ours. Either side of lonely Pathos, Hubris is rising ever higher.The division of women to the left of the Cross, men to the right of it, signals a contrast, almost a contest, between compassion and indifference; but the triangle made by the feet of Christ and the hands of Mary and John - reversing that made by the arms of Christ and the crossbar of the Rood - marks the personal, almost private and familial nature of the event at this late stage when onlookers begin to look elsewhere.

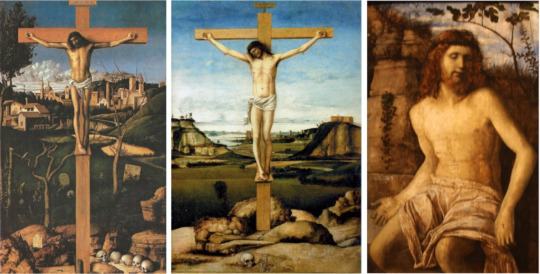

St Francis Receiving the Stigmata, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Detail of rocks

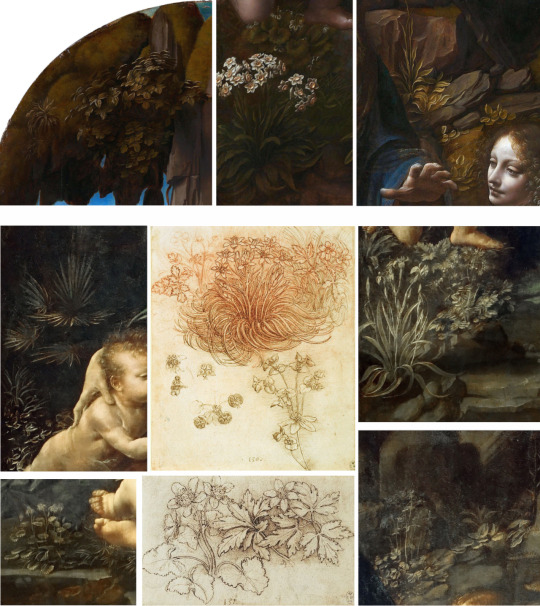

In the Johnson Collection at Philadelphia's Museum of Art we are with Saint Francis kneeling among rocks before his vision of the crucified Christ. The theme of wakefulness and sleeping that was there in the Gethsemane of the Turin Hours has returned with a difference. Here colour is used to suggest, not the contrast between people and their surroundings, but a Franciscan harmony between them. The Saint is clothed in the brown habit of the wilderness in which he prays, while his Brother, linked to him by the cords of their shared vows, is lost in sleep or meditation. What unites this image with the far cooler and more distanced Gethsemane is the treatment of rocks, well in advance of Leonardo’s studies, but no less beautifully observed.

Left: St Christopher Carrying the Infant Christ, Phildelphia Museum of Art; Right: Copy of a lost drawing attributed to J v Eyck of the same scene, Louvre Museum, Paris

Rocks bring us back to Philadelphia, to an exquisite small Saint Christopher carrying the Christchild through shallow water between towering cliffs sprouting trees and bushes. Behind the Child is a lake with distant mountains. Most notable here is the painting of the foreground water - a painterly achievement not attempted in the associated drawing at the Louvre. Such an understanding of water, its surface and depth, the way it moves under pressure of wind and current, is astonishing at so early a date, though we already saw it at Turin, in the Storm on Galilee. There seems to be nothing in the natural world of which Hubert has not made himself master, always on a small scale and with that miniaturist technique that he shared with his brother. We see a mediaeval inheritance being used to quite new ends, and taken to the height of realistic fidelity in a medium that we have to remind ourselves was still in its infancy, What he does is breathtaking in its virtuosity, but also very affecting in its sensitivity and delicacy of touch. he applies his brush as finely as the bow of the most accomplished string player.

Three Maries at the Tomb, Boijmans Museum, Rotterdam

In connection with landscape the last work I want to consider before the Ghent Altarpiece is his painting at Rotterdam's Boijmans Museum, the Three Maries at the Sepulchre.Here, more than ever, we see him using landscape and sky to reinforce a human story. It is not so much a nocturne as an aubade, an evocation of night becoming dawn, well before the sun is up; the sky begins to lighten but night still pervades. The soldiers are asleep, the women are awake; the Angel. like Aurora, female, winged. It is a ghostly hour. The weapons of day, the active life of men, are laid aside as diagonals around the rectangle of the Sepulchre. Beyond that is the still-slumbering city, its towers pushing up into the sky like pinnacles of rock, the bedrock on which the whole scene rests. Like the magician that he is, Hubert can cast a spell of nocturnal obliviousness over what in daylight would be local colours, leaving only certain reserved accents of white in the middle band of the composition - the women’s headdresses, Angel’s robe, a man’s socks - to denote the wakefulness heralded by the whitening sky and a Resurrection on Earth within the Resurrection of Light.

Drapery details from Ghent’s altar of the lamb can be compared with those of the angel’s robes in the Three Maries

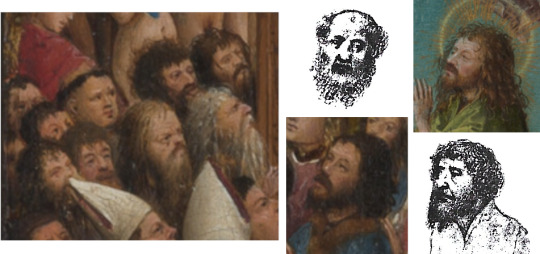

We have arrived now at that heavenly vision that is Hubert’s contribution to the Ghent Altarpiece.The daisies around the feet of Saint Francis, at Philadelphia, return in the grassy bank around the Altar of the Lamb, and there too the drapery of those angels falls in folds like those of the Angel on the Sepulchre at Rotterdam. As in the panels in New York, we find groups crowded together but here transformed into outdoor choirs in a landscape that holds them generously; there is ample space between them in which our eye can move around freely, like a bee, alighting on ever more extraordinary detail. The landscape is idealised, yet recognisably a northern one, of rolling hills and woods between prosperous, aspiring towns, all transformed into a Paradise Garden where every leaf and petal counts and towns become Jerusalems, Cities on the Hill.

On Hubert’s landscape sensibility I have surely said enough to convey how exceptional I think it was and to highlight especially (since landscape was not yet an independent genre) his ability to make it echo sympathetically the pathos of a Crucifixion or other human enactment. His brother also had very considerable gifts when landscape was required, but this particular marriage of mood is not evident in his work; his forte is indoors. If Jan could not have painted The Women at the Sepulchre, Hubert could not have painted the Arnolfini picture. If Hubert’s favourite subject was the Crucifixion in a landscape, Jan’s was the Enthroned Madonna in a room, The contrast between their powers is what my division of labour in the Ghent Altarpiece makes eloquent, There exist some polyptychs, later and elsewhere, that are a mixture of two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture. The Ghent Altarpiece is all painting, but something of that difference is there: Jan’s large figures possess the physicality of sculpture in the round, while Hubert shows himself as more purely a painter. Nothing in Hubert’s contribution reminds one of that; it consummates his love of space and landscape, while the figures, of which there are many, exhibit a variety of facial types significantly different from Jan’s.It is to these that I now turn.

LANDSCAPE WITH FIGURES

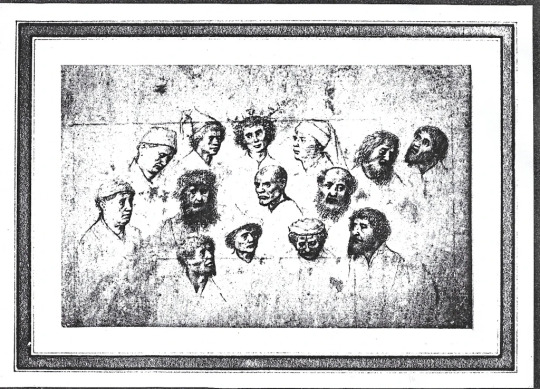

A series of studies of fourteen heads of men, some thought to be for ‘The Adoration of the Shepherds’, variously attributed to J v Eyck and Gerard David

It is fortunate that in the Berlin Print Room there is a sheet of drawn heads that provides exactly what we need. Given the similarities which I shall illustrate, there is no doubt in my mind that this sheet is by Hubert and not by Gerard David or any later artist.

It is helpful to number these heads, so that we can refer to them individually in relation to paintings. Head number 4, for example, reappears as the central figure in a panel at the Boijmans Museum at Rotterdam depicting Saint Catherine led away to her Martyrdom.

in one of a pair of panels at Rotterdam attributed to the ‘Southern Netherlands School’ but much more convincingly to Hubert, albeit in a relatively early phase of his career as a painter of individual panels. This is one of a pair, the companion being Saint Catherine preaching to the Emperor, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Already in these panels we encounter certain Hubertian traits, elaborate metallic tiaras and complicated headgear, the beginning of that fascination with flowered lawn, the springing leaves of grass touched in with the fine tip of the brush, and also hand gestures, witness the left hand of the Saint in the other panel at Rotterdam and the right hand of the Virgin Annunciate in Washington.

Left: St Catherine Preaching to the Emperor, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and its apparent pair, Right: St Catherine Carried Away to be Beheaded, Boijmans Museum, Rotterdam

Comparing the hands of the Virgin the Annunciation at Washington with the hands of the Emperor

Heads numbers 10 and 14 are basically the same head at different angles, and he is a character who appears, wearing dark prussian blue, above the sea in the righthand panel at New York, in the head of Saint John (in green), and several times on the opposite side of the same panel, above the bishops. Number 7, the central head of the drawing, appears on the left panel, on the extreme right, below the left leg of the righthand thief on his cross.

The heads from the earlier chalk study appear in the Crucifixion and Last Judgement panels

These correspondences suggest to me that the Berlin drawing may be contemporary with the New York panels, but the types, which are not Jan’s, recur in different contexts later, which is why I regard the drawing as a helpful index to Hubert’s characterisation.It only represents a few types (or ‘tronies’); the full repertoire, as demonstrated at Ghent, is more extensive. Number 9, to mention another that is very common in Hubert’s work, is well represented at the Albertina in Vienna by the drawing of Saint Andrew holding his Cross.

More heads can be found in St Catherine Carried Away, the Last Judgement and in a drawing depicting St Andrew

All this is not to say that Hubert only did landscapes and Jan only interiors, as we can see in these two examples: the first is Hubert’s tall Annunciation in the Mellon Collection at the National Gallery of Washington and on Jan’s side the Louvre Madonna with Chancellor Rolin.

The Annunciation, attrib Jan van Eyck, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Madonna of Chancellor Rollin, Jan van Eyck, Louvre

Neither Hubert’s smiling Angel nor his Virgin is as Jan would have painted them. The general brownness of the cathedral’s architecture and pavement (reminiscent of the ‘pensive’ brown of the Saint Francis) beautifully conveys the dim stillness of the lofty church, the privacy of reflection, and how revelation, in that ambience, is a matter of inward illumination. The Virgin does not face the Angel nor us, she tilts her head and looks to our right, her gaze on the axis of the dove’s silent swoop. The illumination is in the robe and wings of the Angel, the same colours that are in the stained glass of the window above the Virgin’s head. As in the landscapes, the dim, airy interior of the church matches exactly the mood and moment of the scene enacted; natural and supernatural , visible and invisible, fuse into one.

Facial features in Veronica’s Veil at the Phildelphia Museum of Art can be compared with those of the Virgin from the Annunciation at the National Gallery in Washington

Before leaving this Annunciation it is pertinent to mention a Head of Christ, presented as a Veronica Veil, in the Johnson Collection at Philadelphia, which I give to Hubert. I leave the eyes of the reader to match its features with those of the Virgin.

Drapery is something connoisseurs have to get to know in all its rhythmic convolutions, and nowhere more so than in Netherlandish art where the representation of it reaches astonishing levels of virtuosity in some artists and is always subtly different through whatever hand it is expressed. The ridges and valleys of falling and spreading drapery begin to constitute a landscape in themselves. It is important, therefore to consider Hubert’s own treatment of it which is not greatly different from his brother’s, but subtly so.

Left: Lost illustration of the Virgin and Child from the Turin Hours; Right: The Mystic Marriage of St Catherine, Germanisches National Museum, Nuremberg

Back at Turin, one of the illuminations in the Hours is this one of the Virgin with her Child surrounded by female Saints. The drapery, spreading like foam on a beach onto the flowery meadow, is archetypical of Hubert: very fluent and supple with quite wide spaces between the ridges. We can see this more confidently expressed in a splendid drawing from Nuremberg, of the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine.The sparse folds and rhythms are more pronounced because much later, perhaps even contemporary with his work on the Ghent Altarpiece; the types, female and male, that flank the central group in the drawing are recognisable in the various groups of its painted figures. In the Ince Hall Madonna at Melbourne Jan comes closest to Hubert in the fall of folds that swirl about her, but his drapery later on becomes much more like the painted equivalent of lime wood carving as in the large figures at Ghent.This reflects the difference already noted: Jan tending increasingly towards sculptural monumentality, Hubert remaining more essentially a painter.

Left: Madonna at the Fountain, Hubert van Eyck; Right: Madonna at the Fountain, Jan van Eyck, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp

I have made the point that Hubert was more interested in landscape, Jan in the indoor world. This is nicely illustrated by each of them painting a version of the same subject, the Virgin and Child standing by a Fountain. Hubert places Mother and Child wholly outdoors, grass and flowers at her feet and a bosky background of trees and shrubbery behind a low brick wall. Jan has the Virgin stood on a rich backdrop of brocade that is held up by angels. Yes, there is a rose hedge, low wall, flower-spangled lawn, but it is noticeable how the gold foliage on the brocade is assimilated to the real foliage and real flowers behind and below. Similarly at the top there is assimilation of the angels’ red and gold to the red and gold of the brocade whose edging continues into the edging of their wings. In other words an indoor prop, the brocade, signals that the Virgin and her Child are only half outdoors.

The Annunciation, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A picture that may well belong to the period of the Hubert Madonna at the Fountain is the Annunciation at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, with Mary standing at the doorstep of a lofty portal. Notice the similar treatment in both cases of trees, wall, plants and lawn, as well as the heavy-looking drapery folds in the figure of Mary.

Left: Queen Isabel (St Elizabeth) of Portugal (attrib Massys et al), Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; Right: Cumaen Sibyl from the Ghent Altar

At the beginning of this Study I proposed a very simple division of Hubert’s and Jan’s contributions to the Ghent Altarpiece: all the lower tier of the opened polyptych is Hubert’s, plus, when it is closed, the four arched panels at the top. The latter are interesting because at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin there is a little-known, little-discussed panel of the Holy Elizabeth of Portugal, attributed at times to Quentin Massys and also, vaguely, to a Portuguese-Spanish master, and dated around 1500. To my eye it belongs in an earlier period and its rightful home is in the work of Hubert van Eyck. The head should be compared with that of the Cumaean Sibyl, the lettering with that of her scroll (or any of the scrolls), the tiara with that on the Angel of the Annunciation, the radiance of the aureole with Hubert’s radiances throughout his career.

Portraiture features prominently in the work of Jan van Eyck. We have five separate portraits as well as those of Arnolfini in the London Marriage picture and Chancellor Rolin in the painting of him and the Virgin at the Louvre. It is not apparent from extant work that the same is true of Hubert. The Berlin drawing of heads is a drawing of types, some the same seen from two angles, and as such it represents part of a repertoire of visualised characters who can be introduced into crowd scenes. I may be wrong, but I doubt if many of the heads in the Ghent Altarpiece are portraits. There is, however, one independent portrait that seems different from the Jan portraits and that is the Man in the Blue Cap at the Brukenthal National Museum in Romania. The closest comparison is probably with the heads of the nearest banner-holders on horseback in the Ghent Altarpiece. The vivid Prussian blue is a staple of Hubert’s palette at least as far back as the panels in New York.

Left: Detail of riders from the Ghent panel; Right: Man in a Blue Cap (attrib J v Eyck), Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu, Romania

Naturally, much more could be said (and by others has been) about that complex masterpiece. My concern has been to mark the difference in style and scale between the contributions of the two brothers. They worked in the miniaturist tradition, but they applied their miniaturism - their technical ability to represent very fine detail- in quite different areas. The paradox in Jan’s work is that he actually thought big, not small, in the sense that he conceived large, monumental figures first, and then bestowed on them a wealth of pin-sharp, jewel-like detail. He liked them to fill and dominate the space he gives them, even to the point of making them seem too small for it, as in the Angel and the Virgin in the Ghent Annunciation, both of them large presences in a low-ceilinged room.

Left: Detail from the Ghent Annunciation; Centre: The Virgin of Canon van der Paele, Groeningemuseum, Bruges; Lucca Madonna, Frankfurt

Hubert is the converse of Jan: his figurative scale is smaller, as befits a landscapist, but his spatial scale is vast, as we have seen. Along with the Limbourg brothers and Jean Fouquet, Hubert stands at the beginning of the long story of European landscape art. Part of what distinguishes Hubert in this tradition is what I would call his sympathetic landscape, one that reinforces the human story. When landscape eventually, but gradually, becomes an independent genre, this accord gets lost; not entirely because Poussin is a master of it. In a Claude landscape Aeneas seems an introduced character, adding an extra mythological element to an idealised pastoral; the same is true of Hannibal or Polyphemus in a Turner. In Hubert’s day Man and Nature could be seen together in a vision that sacralises both. That vision involved huge distances, great depth of aerial perspective. After the flatness and abstraction of the twentieth century we have difficulty, pictorially, giving expression to such spatial awareness; a nostalgia can creep into our appreciation of Hubert’s art. We must find new ways.

In view of Hubert’s prodigious talent it is fairly shocking that his art has been so eclipsed by Jan's, so comprehensively overlooked. There should be as many monographs and picture books, articles and exhibitions about him as there are about Jan, but there are not. Ask any person of average visual culture about Jan and the name and some works - probably the Arnolfini picture - will be familiar. Ask about Hubert and the response is a mystified, interrogative ‘Hubert?’ The essential purpose of this Study has been to remove that question mark. Like the remarkable Master of the Pieta de Villeneuve (at the Louvre) Hubert is a great artist whose fate has been to have his work confused with that of another great artist, in the Master’s case with Enguerrand Quarton, in Hubert’s case with his brother. It is in this sense that I claimed for connoisseurship the power, sometimes, to resurrect. The resurrection, however, is not instant or miraculous but a patient, collective process that, once begun, must continue.

Cityscape from the Ghent Altarpiece

Just to scroll back through the coloured illustrations of this Study is to be reminded of medieval illuminations, their bright, unfaded, undarkened colours, and of course their miniaturism. Yet in other ways Hubert looks forward, not backward, moving clear-sightedly out of the Middle Ages into the humanism of the Renaissance and on towards all that followed in our European landscape art. We owe him, I think, a huge debt.

On the subject of debt, I wish to acknowledge here what I owe to Emily Wetherell who has helped me so much, and so tactfully, with this Study and many of its predecessors. Not only has she been the technical assistant to a technophobe, she has done a great deal of picture research, checking the locations and current attributions of pictures and drawings, as well as making numerous suggestions about how to improve the text. Crucial to the visual argument of all these Studies, however, is the juxtaposition of images, and she has contributed materially to making clearer those comparisons and connections that are at the heart of any serious connoisseurship.

#studies in connoisseurship#hubertvaneyck#vaneyck#jan van eck#hubert van eyck#art history#connoisseurship#miniatures#turin hours#illumination

1 note

·

View note

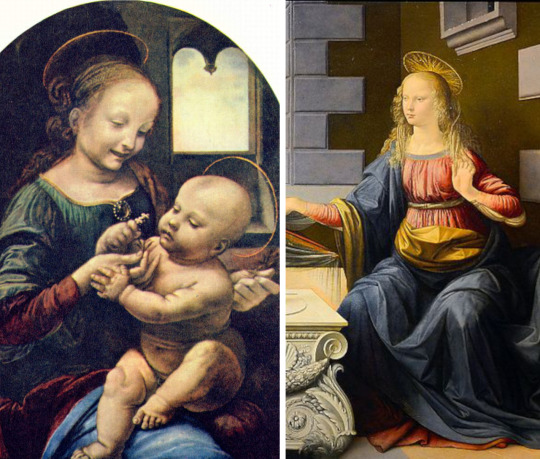

Text

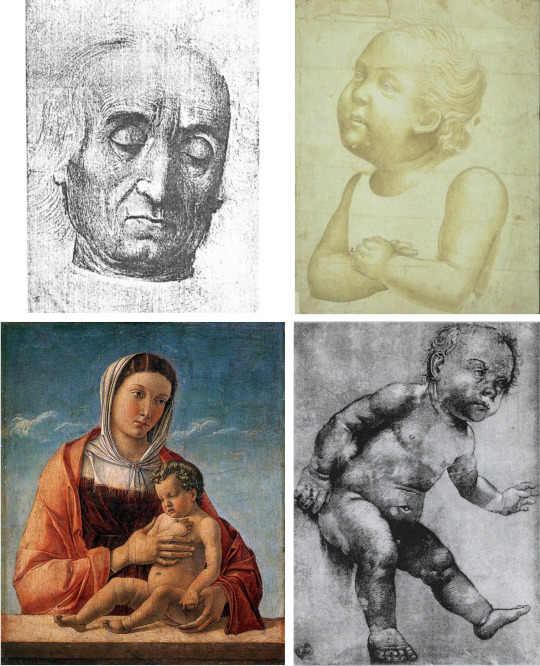

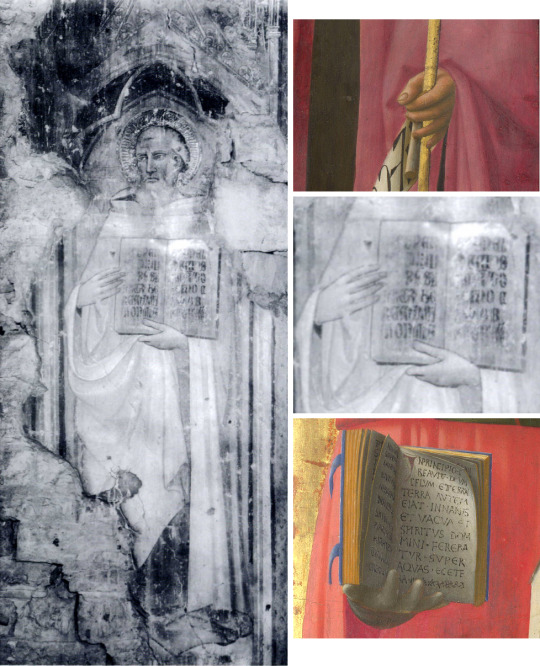

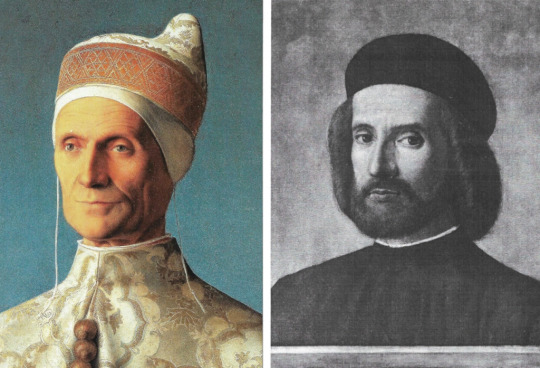

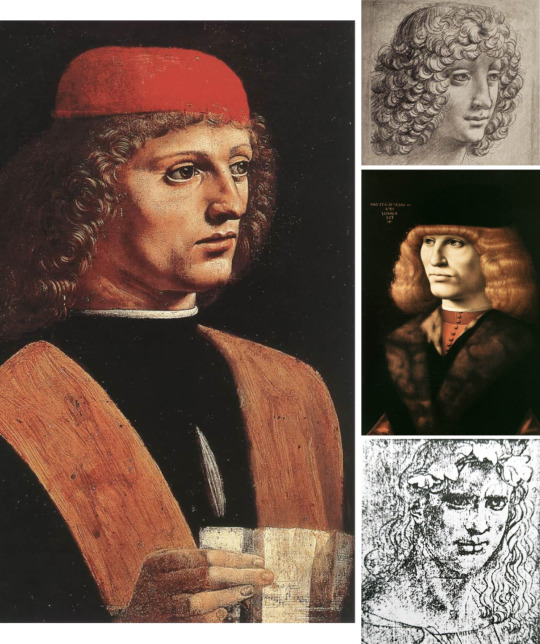

Balkanizing Bellini pt 4

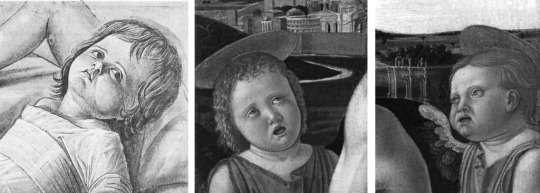

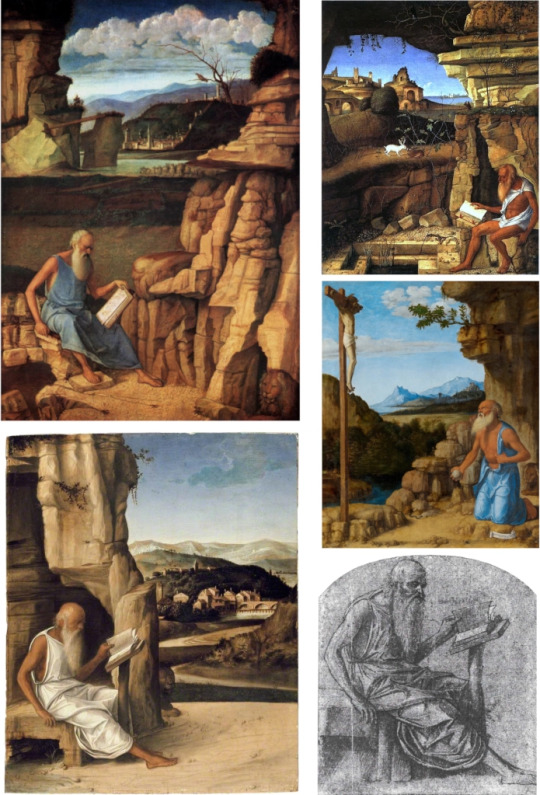

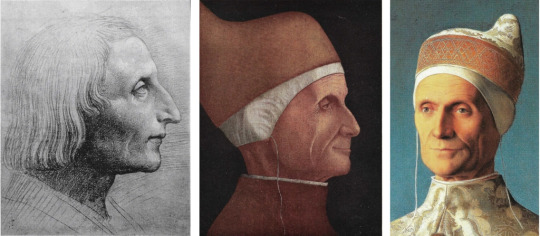

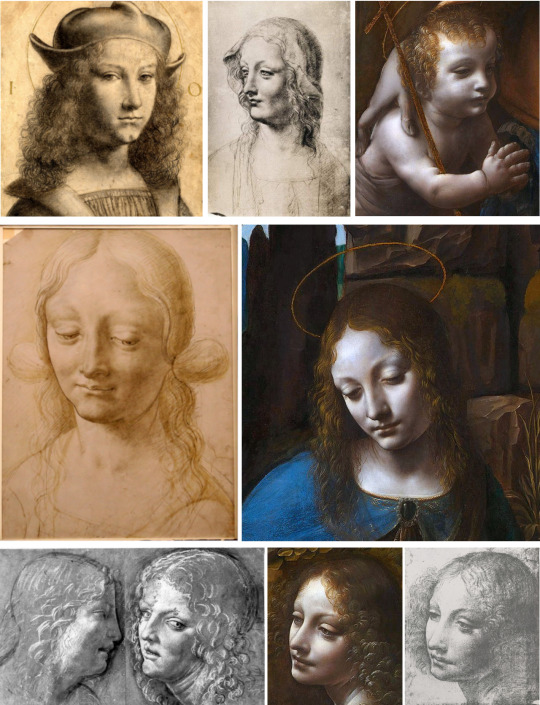

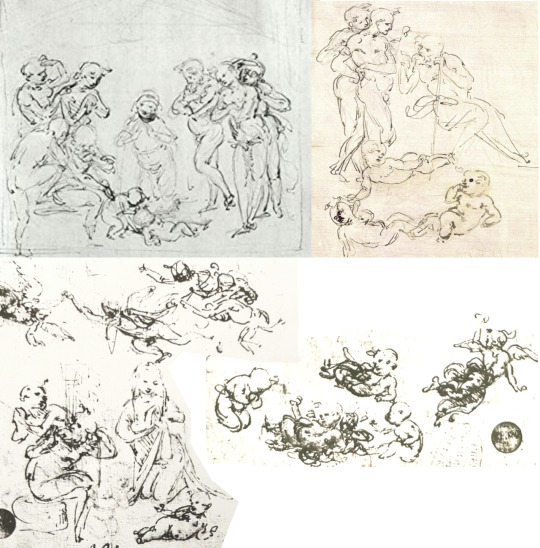

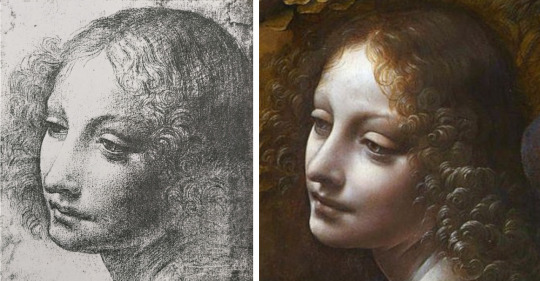

Study for Figure of the Infant Christ (attrib Giovanni Bellini), Ashmolean Museum Oxford

To introduce a fourth ‘Giovanni Bellini’ artist, I choose this drawing, an exceptionally strong and beautiful one, in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. As expected, it is catalogued as by Giovanni Bellini and the attribution has not been challenged. We are shown the Christ Child with raised knees, his head looking up at us from what is destined to be His mother’s lap. His short tunic, heightened with white, has a broad sash round his upper torso; every crease in it is finely modelled. In the upper part of the sheet is a separate study of raised legs, with shadows behind the feet.

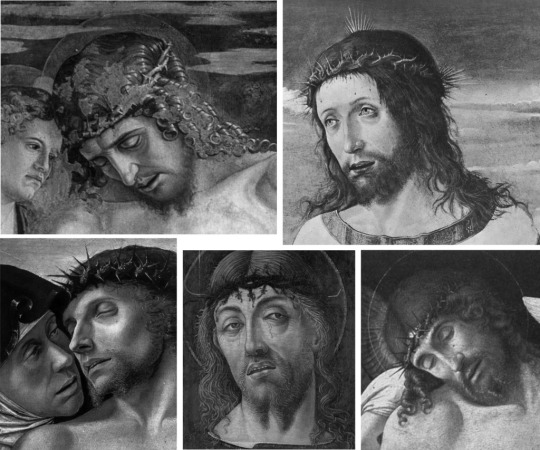

*With such strength of modelling evidenced in a largely monochrome drawing, it can make sense to sometimes use black and white reproductions of paintings to better bring out this quality in the artist’s work; one can often see the form in it more clearly without the distraction of colour. In this study I have included some monochrome images alongside the colour reproductions to best illustrate this.

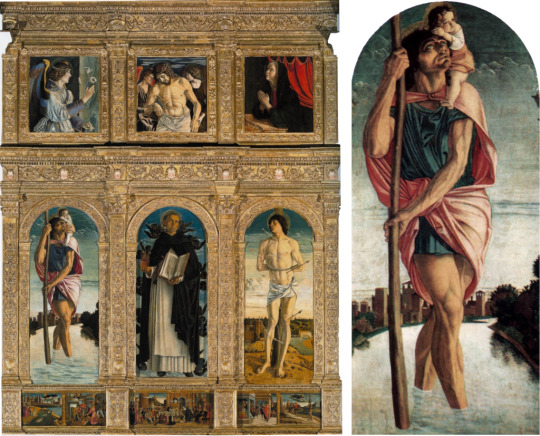

Left: Polyptych of St Vincent Ferrer, Basilica of SS Giovanni e Paolo, Venice ; Right: St Christopher carrying Christ from the Polyptch

Left: Close up of the Infant Christ on St Christopher's shoulder from the Polyptych; Right: Detail from Ashmolean Study

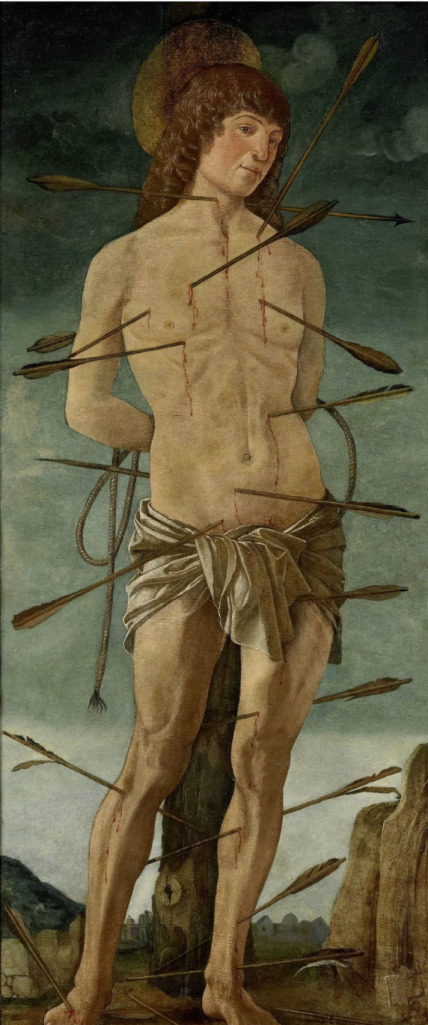

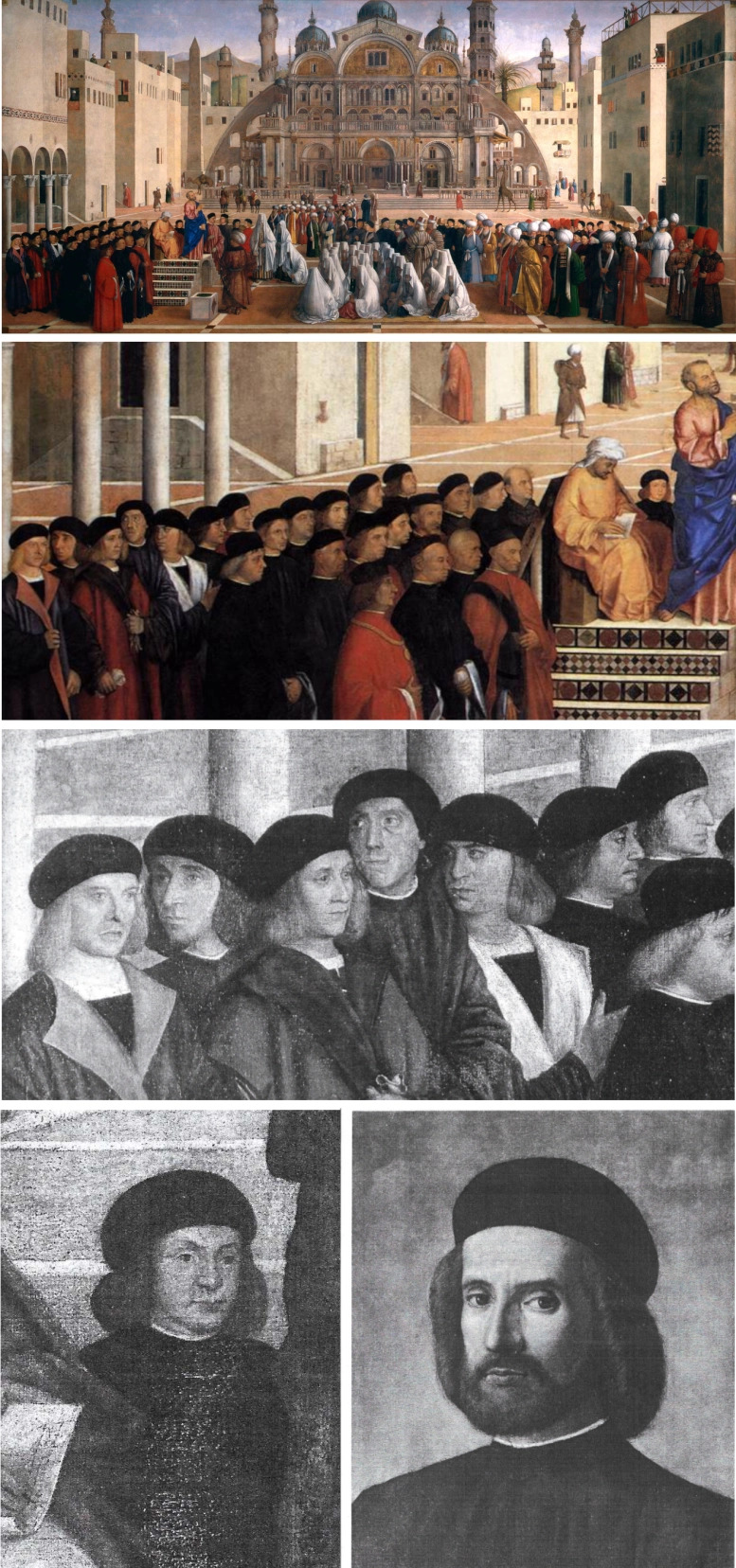

Clearly this is the type of the Child borne on the shoulder of Saint Christopher in the Saint Vincent Ferrer polyptych in the Basilica of SS Giovanni e Paolo in Venice, the same polyptych whose three predella panels we encountered in the discussion of the third ‘Giovanni Bellini’ painter, and must therefore disregard in our study of this fourth one. The six principal panels, three square above three arched, give us a good idea of this artist’s mature style and furnish us with a useful reference-source for further attributions. The Pieta, of Christ supported by Angels, at top centre, leads easily to a number of other things: to a Pieta in the Museo Civico at Rimini, to the Pieta at the Brera Gallery in Milan, to the Christ Blessing at the Louvre in Paris, and to a very impressive Head of Christ in the Kroller-Muller Museum at Otterlo in the Netherlands

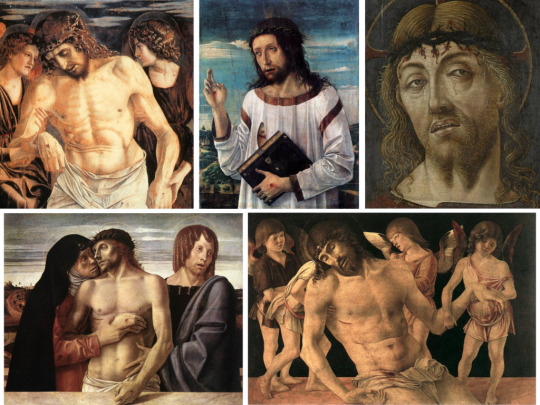

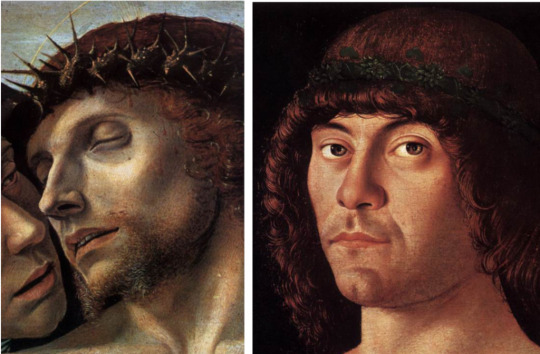

Clockwise from Top Left: The Dead Christ supported by Angels from the Polyptych ; Christ Blessing (attrib Bellini), Musée du Louvre, Paris ; Christ of Mockery (attrib Vittore Crivelli), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo ; The Dead Christ supported by Angels (attrib G Bellini), Museo della Città, Rimini ; Pietà (attrib G Bellini), Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

What is common to these images is principally a portrayal of Christ that is peculiar to this artist and not to be found in other ‘Giovanni Bellini’ painters looked at so far in these Studies, nor, as may appear subsequently, in any of those remaining to be considered. It is difficult to characterise this portrayal in words, but there is an asceticism expressed in the ‘hard’, chiselled planes of His face that brings us closer to Mantegna and the face of his Lamentation of Christ (as seen from His feet) in the Brera at Milan. Both men have conveyed a mood of silent acceptance of suffering and of death, and silent compassion with it. This lends itself naturally to a subdued and sombre palette, as if colour were drained out with the exhaustion of the breath of earthly life. The narrow range of subject-matter - variations on the Pieta theme - is indicative of the painter’s wish to focus on this ‘dead end’ of the Passion Story.

Details from the above paintings, highlighting the chiselled planes of Christ's face

The dead Christ and Three Mourners (Mantegna) ; our artist's work bears some similarities with this, more so than with other works by Bellini

The head of Saint Sebastian in the panel at the top and right of the Saint Vincent Ferrer Polyptych has, to my eye, a sufficient generic likeness with that of an Unknown Man in a drawing, below, from Besancon. I have not found any ‘home’, as Berenson would say, for this fine work except in the oeuvre of this artist, and it certainly exhibits all the strength of modelling that characterises his art.

Portrait of a Man, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d'Archéologie, Besançon can be compared with St Sebastian from the Polyptych of St Vincent Ferrer

One has only to consider this portrait drawing to realise that this is an artist of great ability. To speak of assistants in the Bellini Workshop as if there was one great master in charge and minor talents at work around him is to grossly underestimate those talents, anonymous though they are and may remain. Their number is unknown and changed over time, but they were artists with varying temperaments and varying preferences when it came to subject-matter. It is hard to imagine the painter of the Madonna of the Meadow being regularly assigned Crucifixions - he was clearly a Madonna specialist - while this fourth artist, by contrast, must have been an obvious choice for the later scenes of the Passion.

The Calvary (attrib G Bellini), Musée du Louvre, Paris

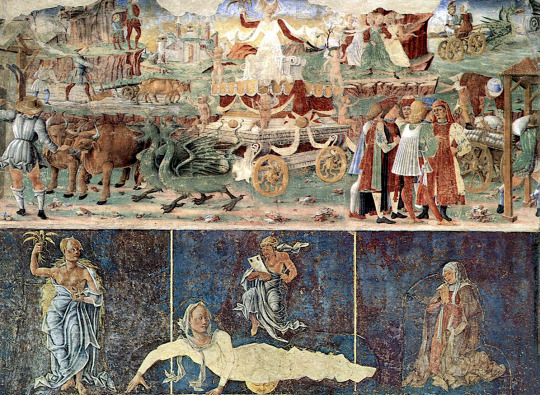

Spacious landscapes and warm cool colours found in both the Brera Pietà and The Calvary

For me, one of the loveliest of this artist’s works is in the Louvre, The Calvary with Mary and Saint John. The sentinel figures either side of the Cross stand close to the picture plane, They perfectly balance the figure of Christ, but are separate enough to allow the eye to pass on into the spaciousness of a dawn landscape of sleepy brown hills, untravelled roads, grey-blue water of river and lake, grey-blue mountains in the distance. Trees - some breaking the skyline - provide markers plotting spatial relations. Everything is carefully composed: tall tree to left, tall tower to right, the Rood down the middle; its crossbar at the top, along which Christ’s arms are stretched, echo the flat line of cloud. All the colours, warm and cool, are subdued to the red robe of John and the blue one of Mary. Overall the mood is quiet, sombre, still.

This Louvre Calvary brings us back to the mood described earlier, regarding illustrations 6 to 11. It situates the Crucifixion in a landscape that seems to reinforce the solitary nature of the foreground vigil. Such emotional isolation of the Passion of Christ (when all the crowds and public spectacle are gone) is what appears to most engage the imagination of this artist, and it returns us to a picture such as the Brera Pieta which ‘bears witness’ by bringing the viewer as close as possible to the protagonists, eschewing all distraction, rather as Caravaggio was to do much later, and some war photographers do to this day.

Portrait of a Humanist (possibly Raffaele Zovenzoni or Peter Luder, attrib G Bellini, da Messina, Veneziano et al), Museo Castello Sforzesco

I suggest also a fine Portrait of a Young Man at the Castello Sforzesco museum in Milan. Note, as characteristic of this artist, the thin, pale outlining of the top of the upper lip and how this is continued into the pronounced fluting below the nostrils. This is all closely paralleled in the Brera Pieta where Mary shares as well the Young Man’s dimpled chin. His warm flesh-colour and the strong structure of the face with its prominent cheek bones fit well with what we have already encountered. Finally, what little we see of the toga-like robe knotted on his left shoulder has folds comparably treated in the robe of the left angel in the Pieta of the Saint Vincent Ferrer polyptych. It could be that the Young Man was the model for a Saint Sebastian, now at the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam and ascribed there to Francesco Bonsignori.

Distinctive lines of the lips and cleft chins present in both the Brera Pietà and the Humanist

Folds of brown cloth from the Humanist (left) and the Polyptych (right)

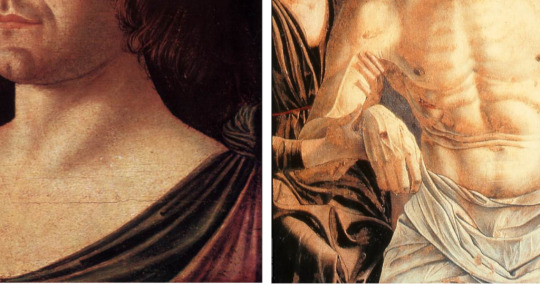

Saint Sebastian (attrib Bonsignori), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Facial similarities between the Humanist and Saint Sebastian

From Left: The Annunciation detail from the Polyptych ; The Greek Madonna, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan ; Lochis Madonna, Accademia Carrara, Bergamo (all attrib G Bellini)

If we return to the Saint Vincent Ferrer polyptych in Venice (always ignoring the predella panels) and focus on the panel at top right showing Mary praying as she faces, across the Pieta, the Announcing Angel, it is possible to add to add to our oeuvre for this artist two fine Virgin and Child paintings, one with a Greek inscription that is in the Brera Gallery at Milan, and a later one known as the Lochis Madonna in the Accademia Carrara at Bergamo. The basis for these additions lies mainly in the facial type that is common to both and shared with the Mary Annunciate of the polyptych.

The Lochis Madonna is particularly rewarding for its literally arresting composition: the calm, pensive Mother restrains a very energetic Child who recoils from her as if startled by something she is not aware of - that prophetic premonition of the Passion, perhaps, that is more often suggested by symbols. This recoil to the right is countered by the veining of the marble making little ‘waves’ that run up to the left while, under the ledge, they flow to the right. Rhythmically and dynamically the folds of drapery on both Mother and Child are carefully disposed to form a thoroughly original design that makes this one of the best of all Bellinian Madonnas.

Left: Detail of an Angel from the Polyptych Right: Drawing of an Unknown Woman, whereabouts unknown

Thinking of these Madonna paintings in conjunction with the Angel of the Annunciation in the Saint Vincent Ferrer polyptych I am tempted to add a boldly modelled chalk drawing of an Unknown Woman, her head half-turned to our right. This was exhibited a long time ago as by ‘Giovanni Bellini’ in a 1966 exhibition at Monte Carlo of drawings from the Collection of H de Marignane. Where it is now I have no idea.

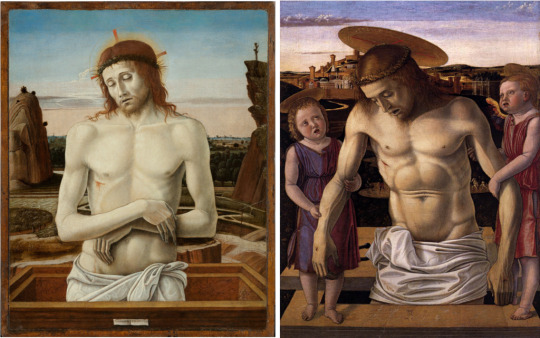

Two early 'Pietà's, Left: Museo di Poldi Pezzoli, Right: Museo Correr (both attrib G Bellini)

Comparing the Study of Infant Christ from the Ashmolean with the angels from the Correr Pietà

Finally here are two pictures of Christ stood in the Tomb, one, in the Poldi-Pezzoli Museum at Milan, where His arms are crossed, the other where they are held by two child angels, in the Correr Museum at Venice. I am reluctant to posit any chronology, but stylistically these do look earlier than the works considered above, though I can see similarities between the supporting Angels in the Correr picture, especially the right-hand one, and the Ashmolean drawing with which we began. The maturity that came later is evident if one compares these works with a comparable subject, a Dead Christ supported by Two Angels, at Berlin. There the Angel to our left is much closer to the Angel of the Annunciation of the Saint Vincent Ferrer polyptych.

Left: Berlin Pietà (attrib Bellini), Gemälde Gallerie, Berlin ; comparable to the previous Pietàs

Details from the Polyptych (left) and the Berlin Pietà (right)I

t is more than likely that in the future other works by this artist will be added to the tally, but for now I hope his separate identity has been established beyond reasonable doubt, and that what I attribute to him demonstrates a major talent, capable of producing drawn and painted images of exceptional plasticity. Strong modelling is at the service of the equally strong emotional themes of Christ’s Passion, most notably the Pieta. The frequency of those subjects suggests where his expressive potential lay.

Henry Moore was inspired by the Brera Pietà (left) to create a series of sketch studies, including this one from the Henry Moore Foundation

It was this emotional charge, combined with the sculptural modelling that must have impressed Henry Moore sufficiently to make him want to draw for himself (in 1975) the juxtaposed heads of Mother and Son in the Brera Pieta. That Moore thought the artist was Giovanni Bellini was natural enough, but in truth the name of the artist did not matter to him; he simply identified with the representation of a subject dear to him by a fellow artist of another age. The identity of the artist only matters if we care to identify the particular hand at work, and the imagination that dictated the form and style of what we see. As connoisseurs we need not to be fixated upon names. A distinguished artist like this one may never have a name attached to him, but what is left of his life’s work can live on, if we can indeed distinguish it.

#Giovanni Bellini#anonymous artist#renaissance art#accademia venice#brera#painting#art history#connoisseurship#studies in connoisseurship#passion of the christ#pieta#henry moore#mantegna#saint sebastian#saint christopher#besancon#kroller muller museum#ashmolean

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

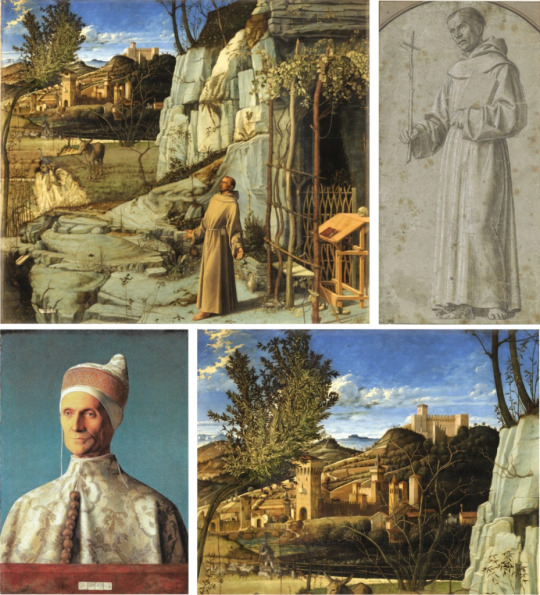

Balkanizing Bellini pt 3

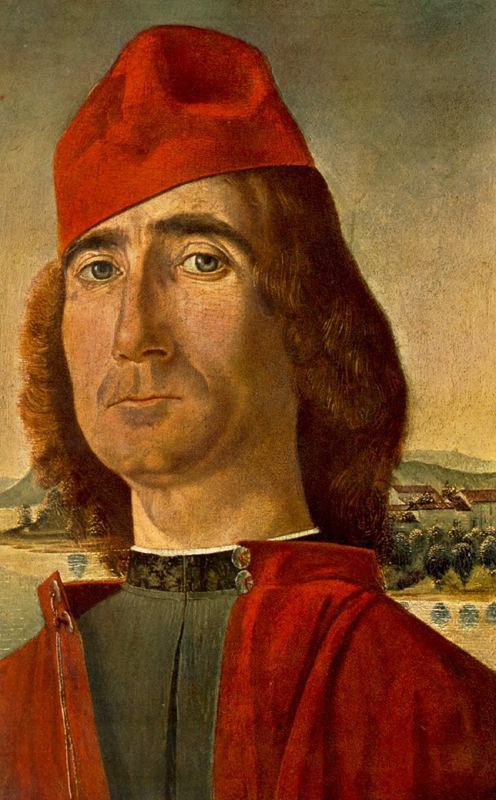

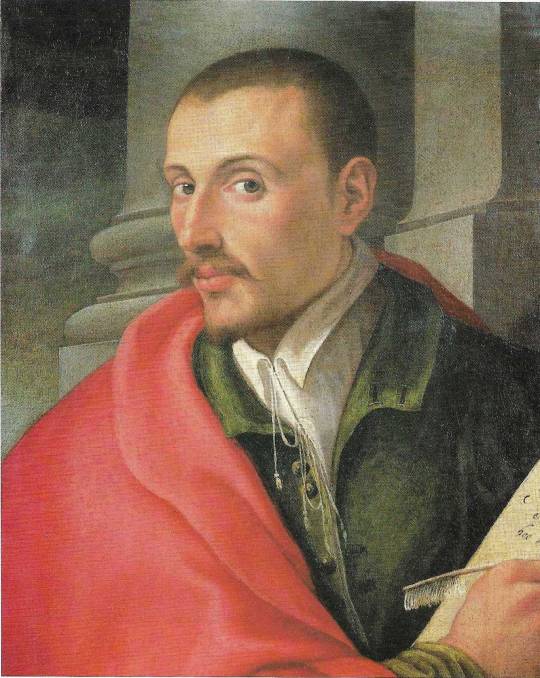

In the Correr Museum at Venice is this Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap. As we see it now, the Man is off centre, looking sideways down on us; with his long face, long neck and jutting lip, he is quite a superior and forbidding presence, the kind that makes one feel judged. His cap is worn aslant, so it almost reaches his right eyebrow.

From Left: Portrait of a Man with a Red Cap, Museo Correr, Venice ; Silverpoint drawing of an old man's head looking down (from a sale at Sothebys December 1920) ; Portrait of a Man, National Gallery Washington D.C.

If we look at his eyebrows, nose and thin mouth, I think there is a striking similarity with the facial features in a silverpoint drawing sold by Sothebys in 1920. The structure of the face is also similar, and rendered, in the drawing, with fine stroking movements of the metal pencil that follow the rhythms of the flesh while telling us clearly where the bone is.The man is old and has downcast eyes. A younger man with eyes like those of the Man at the Correr Museum appears in a painting at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. and variously ascribed , to Alvise Vivarini, Bellini and Antonello da Messina. This, too, I would ascribe to the artist we are concerned with.

Left: Man praying ; Right: Profile of a old man (whereabouts unknown. Images: Witt Library)

Focussing on the mouth in Illustrations 1 and 2, and on the nose in the old man, I think one can extrapolate from a frontal view what a side one would look like, and thereby add two profile portraits of men, one at the Accademia in Venice, the other at Marseilles.

Left to Right Top: Old man looking down ; Drawing of a child with arms folded, from an image of St John, Musee du Louvre, Paris ; Bottom: Frizzoni Madonna (attrib Bellini) Museo Correr ; Drawing of the Christ Child, Uffizi Gabinetto Florence

Remembering the silverpoint ‘stroking’ in the drawing of the old man takes one to a drawing of a boy, probably the child Saint John, in the Louvre, and that in turn takes us back to the Correr Museum and a Mother and Child painting, the Child held on a parapet with blue sky and a bit of cloud behind the Mother. Another drawing, for a Christchild, at the Uffizi, exhibits the same, characteristic stroking draughtsmanship. An indicative aspect of the Correr Madonna is its colour scheme: a rose overmantel that is bleached by the light, and a deep maroon undergarment, the Madonna’s hair in much the same hue.These colours, together with the long, separated digits of the hands should be borne in mind when we look at the next item.

The Transfiguration (attrib Bellini) - Correr Museum

Amazingly, the Correr Museum yields a third and much more ambitious painting, The Transfiguration of Christ, that reveals, in the two figures to our left, one above the other, the same combinations of colours as in the Madonna.

Two drawings from the Uffizi (attrib Giovanni Bellini)

When we look at the treatment of drapery in the figure of Peter and of the still-sleeping Apostle, confirmation that the picture is by the same artist comes in a drawing at the Uffizi of a sleeping Apostle with his head against a tree, drawn in that now familiar, stroking style , and another, also at the Uffizi, of a youth sitting on a rock and looking upwards in wonder.

Whereabouts unkown (Images from Witt Library)

Two further paintings, one of a group of women around the Mother and her Child, the other of the Baptism of Christ, reveal considerable gifts of composition with a noticeable preference for arcs that link draperies and limbs.

St Christopher with the Christchild - Musee du Louvre (image from Witt Library)

Our next stop is a finely finished drawing in the Cabinet des Designs at the Louvre which shows Saint Christopher with the Christchild holding his head, legs either side of his neck. It is unfortunate that the drawing has suffered damage that literally defaces both of them, Saint and Child. However, there is plenty of evidence throughout that we are looking at a drawing by the artist we are interested in, and not Jacopo Bellini.Consider, among other things, the Saints left hand vis-a-vis the Correr Madonna’s right one.

Details of hand from Frizzoni Madonna (top left) ; St Christpher (top right) and the Agony in the Garden - National Gallery London (bottom)

How this Louvre drawing relates in time to the National Gallery’s Agony in the Garden I have no idea, but it does contain descriptive features to be found in the London picture.

Details of steps and tress from the Agony in the Garden (left) and St Christopher (right)

On the left side of the painting is a leafless tree with twisted branches like arms in agony. On the right side is a river that passes over a bridge connecting a higher bank with a lower one by means of steps leading down. In the lower right corner is a palisade of loosely woven branches. All these details are present in the Saint Christopher drawing. The latter’s minutely worked textures made of long thin strokes and flecks and dots are entirely consistent with everything already encountered

Christ, praying on the rocky knoll faces a vision in the sky of the naked Child holding the cup. This Child with his pronounced tummy resembles two similar children, amoretti, in a painting at Chicago (Ryerson Collection).

Details from the Agony in the Garden (left) ; Two Putti (right, attrib Mateo di Giovanni) Art Institute of Chicago ; Arion riding a Dolphin (right) Ashmolean Museum

Another naked child relatable to the style of this artist is Arion playing music on the Dolphin’s back, in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. I believe that this very charming picture, with its evocative sea- and mountain-scape, is also eligible for inclusion somewhere within this artist’s oeuvre.