Video

tumblr

by Katrin Tiidenberg, Natalie Ann Hendry & Crystal Abidin

Katrin Tiidenberg, Natalie Ann Hendry, and Crystal Abidin offer the first systematic guide to tumblr and its crucial role in shaping internet culture. Drawing on a decade of qualitative data, they trace the prominent social media practices of creativity, curation, and community-making, and reveal tumblr’s cultlike appeal and position in the social media ecosystem.

"Sharp, perceptive, and empirically solid, this book is nothing short of a scholarly eulogy to the platform and community that tumblr used to be."Jenny Sundén, Karlstad University

"So much more than just an overview of tumblr, this book is a generous examination of an all too rare form of online sociality – and a platform designed to help it thrive. It is also a sharp reminder that, though platforms can protect their communities, they can just as easily cut them off at the knees." Tarleton Gillespie, Microsoft Research

look at the extended table of contents here

UK: September 2021 / US: November 2021 | Paperback 978-1-5095-4109-6 | £15.99 / €19.90 / $22.95

20% discount*: go to politybooks.com and use code POL21 (*promo code is valid until 31/12/2021)

Free exam copies are available to full time professors teaching classes of over 12 students for whom this book may be appropriate as a core text. For more information, get in touch with us [email protected]

#tumblr#book#research#tumblr research#katrin tiidenberg#crystal abidin#natalie ann hendry#fandom#fandom studies#LGBTQ#queer studies#mental health tumblr#social media studies#platform studies#digital cultures#creativity#curation#community making#K-pop#K-pop fandom

335 notes

·

View notes

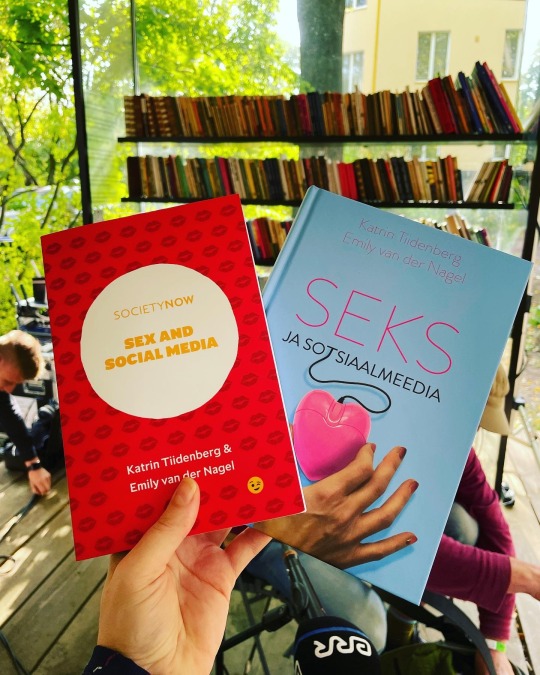

Photo

I can’t even begin to explain how amazing AND bananas it feels to have written, as an Estonian, a book in English with Emily van der Nagel that is then translated into …wait for it… Estonian. But here it is, Sex and Social Media, now in English (also audiobook) and Estonian

#books#translation#Katrin Tiidenberg#emily van der nagel#research#social media research#sexuality#sex research

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi tumblr, meet tumblr

I cannot wait to hold this new baby that Natalie, Crystal and I made from 3 x of a decade of researching, using and loving tumblr.

We also have lovely, generous, wise back cover blurbs, but the published hasn’t published those yet, so I guess that’ll be another post.

Preorder here or here.

We talk about why tumblr was / is so special, how it shaped the digital cultures of the 21st century, its transforming place and role within the social media ecosystem, but we also talk about the practices of curation, creativity and community making. Of course, we also talk about fandom tumblr, queer tumblr, NSFW tumblr, mental health tumblr, social justice tumblr; about reblogs and attention and popularity, about fanmail and notes, and blog themes, about obscure humor and the deep deep well of memes.

#tumblr book#book about tumblr#digital ethnography#platforms#platform studies#social media research#katrin tiidenberg#crystal abidin#natalie ann hendry#memes#fandom#queer tumblr#mental health#k-pop#just tumblr things#just tumblr being tumblr#social justice

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

a talk on contextual methods for studying visual/multimodal social media

Sharing a talk I did in March for the British Sociology Association’s event on Creative Ethnographic Methods. It’s about an hour on contextual methods for analyzing social media practices and content, specifically on the tactics of abduction, imitation and sense making for researching visual or multimodal social media.

I was quite happy with it, I think. Might work for teaching too, if you need a video content / guest lecture

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5k4MMuHq9s

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

In December, Susanna Paasonen and colleagues organized a symposium for their project Intimacy in Data-Driven Culture. Facebook’s Christine Grahn talked about how FBs community standards work, I talked about the concentration of platform power as evidenced in deplatforming of sex (including, from tumblr) and Nalubega Ross talked about sexual rights.

#lecture#talk#academic talk#platforms#content moderation#community moderation#Social media#social media research

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sex and Social Media on Techtopia podcast

A while ago Henrik Føhns reached out and said he was reading Sex and Social Media (co-written with my amazing co-author Emily van der Nagel) and would like to have a conversation about it on his podcast Techtopia. It turned out that Techtopia is a podcast of the Danish Society of Engineers, which I found quite amusing. We had a very interesting conversation about hashtags and content moderation and platform governance and a bit about sex on social media. The conversation kind of fluidly meanders between danish and english, so I suppose is more enjoyable to those who speak both.

https://ida.dk/viden-og-netvaerk/techtopia/techtopia-164-nul-sex-paa-sociale-medier

#books#content moderation#hashtags#deplatforming#deplatforming of sex#fosta sesta#platform governance#techtopia#podcast

0 notes

Text

How to read (at MA level, for exams/quizzes)

We are using reading quizzes to enhance our Zoom classes this semester, and when I asked, my MA students thought some guidance on how to read efficiently for comprehension might be useful. So, this is a quick collection of advice that I find useful from a variety of excellent sources (some of which are linked in the end).

1. Prepare your mind to read this text. If it’s an article, it has an abstract, read the abstract, then read what the subtitles of different parts are. If it is a book chapter, read the introduction and take a look at what the subtitles of subchapters are.

What is this text about?

Why has it been assigned? What topic does it link to? How does it link to what you already know or what has already been covered in class?

2. Take notes while you are reading. What is important to remember is that note-taking is an exercise that starts from a frame or a question. What are you reading FOR?

A. Are you reading to comprehend the text and get everything that your teacher / supervisor probably considered relevant (and thus may have put on a quiz or an exam) out of it?

B. Are you reading because you are looking for ideas, inspiration, research findings, conceptual frameworks for a particular topic (this will happen when you are working on your own thesis, research or your own writing)?

C. Are you reading to get an overview of the state of the art in a field as you are embarking on a new research project?

These will lead to different types of reading / different types of note taking. For B it might be a good idea to take notes freehand, for example, my colleague Jenny Hagedorn recommends restricting yourself to one A4 page for notes - instead of copying quotes, write down key words/ideas/things you’re not sure about and link them together as you read...it becomes a visual map of the text - excellent reference point for discussion or quickly sourcing. For C it might be a good idea to start from skimming a number of texts to then decide on a smaller number to read critically. Critical reading is guided by questions like these (by Wray and Wallace)

1. Why am I reading this?

2. What are the authors trying to achieve in writing this?

3. What are the authors claiming that is relevant to my work?

4. How convincing are these claims, and why?

5. In conclusion, what use can I make of this?

However, whatever you read for; you should read FOR THE ARGUMENT. Most of the key content in the text is given in the form of arguments. So, it is useful to be able to recognize arguments. If you haven’t read a lot of academic writing Graff, Birkenstein & Durst (2018, 11 - 12) have a MASTER TEMPLATE for writing arguments, or their “they say, I say” model:

In recent discussions of …. , a controversial issue has been whether …. . On the one hand, some argue that …… . From this perspective, …… . On the other hand, others argue that ……. In the words of ….. , one of this view’s main proponents, “……”

According to this view, …… In sum, then, the issue is whether …… or ………. My own view is that ……… Though I concede that …….. I still maintain that ……… For example, ………. Although some might object that …….. I would reply that …….. . The issue is important because ……….

Taking it line by line, this master template first identifies an issue in some ongoing conversation or debate (“In recent discussions of a controversial issue has been”), and then maps some of the voices in this controversy (by using the “on the one hand / on the other hand” structure). The template then introduces a quotation (“In the words of”), explains the quotation (“According to this view”), and states the argument (“My own view is that”). It qualifies the argument (“Though I concede that”), and supports it with evidence (“For example”).

If you are reading for comprehending / to study for an exam or quiz, I recommend:

1. Whether you highlight, underline or take notes, pay attention to the elements of the argument as outlined in the They say, I say model above. Important stuff is bound to congregate in the neighborhood of

where the author is making conclusions or summarizing (often they will spend a paragraph or two explaining something and then summarize the main finding in a conclusive sentence),

when the author is categorizing (making lists, or saying there are two reasons, or three problems, or four approaches),

when the author is making statements about something causing or related to something else (writing that something is because of, caused by, leads to, explains, or comes after questions that start with "why" and "how"),

when the author is engaging with existing scholarship in ways that elevate it as most important (this is where they will condense and paraphrase what they think is important knowledge in the field, look for when the author is named not just cited;

and whenever "some scholars have argued," "there is research that," "Researchers claim," etc is used.

2. If you highlight:

research suggests that just highlighting is not very efficient. Rather, if you highlight, add your own comments in the margins, as notes or in a separate file. If you read digitally, I recommend copying out the highlighted snippets and adding your own comments to them. Make sure you add your comments in a visibly different way, I put in my initials KT in bold to indicate that this is where the quoted text ends and my own thoughts begin.

Some people color code their highlights (by level of importance or by category, i.e. yellow is theory or concept, blue is methods, pink is findings).

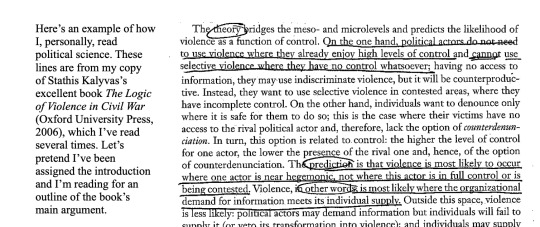

3. If you underline: I like this advice by Amelia Hoover Green (see here for more)

Green explains her system: “First, signposts. I circled “theory” in the first line because I imagine he’s going to tell me what it is. I also circled “prediction,” because I want to know what his theory predicts will happen in the real world. I circled “in other words” because that suggests he’s going to restate something important (in this case, the prediction). After circling, I read carefully in the neighborhood of my key words and underlined a few key sentences. Your goal: underline no more than a few sentences on any page.”

After you are done reading and taking notes, review your notes and try to return to the questions you asked yourself when preparing your mind to read

What was this text about? What was its main argument?

How did it link to what you already know or what has already been covered in class?

What new things, terms, concepts you learned

Links to more advice:

Amelia Hoover Green advice on how to read https://www.ameliahoovergreen.com/uploads/9/3/0/9/93091546/howtoread.pdf

Terri Senft’s awesome guide to reading visually https://www.dropbox.com/s/ock2oep04thgla9/READING%20VISUALLY_SENFT.pdf?dl=0

Elsa Devienne’s “How to read an academic history article or chapter” infographic https://twitter.com/E_Devienne/status/1305899621064028161/photo/1

Mike Wallace’s and Alison Wray’s book Critical Reading and Writing for Postgraduates https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/critical-reading-and-writing-for-postgraduates/book245471

Raul Pacheco-Vega’s extensive collection of resources on reading strategies and note taking strategies (in the form of very accessible blog posts)> http://www.raulpacheco.org/resources/reading-strategies/

This thread started with A LOT Of recommendations https://twitter.com/eveewing/status/1143345817463472128

Ashley Rubin’s’ guide to reading non-textbook texts: https://www.dropbox.com/s/f32p4xsaqzddo8a/Reading%20Guide.pdf?dl=0

Miriam Sweeney’s blog post on how to read for gradschool https://miriamsweeney.net/2012/06/20/readforgradschool/

Jessica Calarco’s blog spot on reading for meaning in the academia http://www.jessicacalarco.com/tips-tricks/2018/9/2/beyond-the-abstract-reading-for-meaning-in-academia

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

We were invited to Dildorks to talk our new book and it was a lot of fun. Check it out for a conversation on what even counts as sex, platform politics, content moderation, Tumblr, Reddit, Instagram, nudes and whether or not sex belongs on generic social media platforms

0 notes

Photo

My new book - co-authored with Emily van der Nagel - is out!

You can see the early praise above. We also have our first reviews in English, by Amy from Coffee and Kink and, should you read Estonian, by Airika Harrik.

You can read a free chapter here.

You can get a 30% discount if you use the code SOCIAL in Emerald’s store.

There is also an audio book (we are very excited about it), performed by Kelly Burke. It is available via audible but also elsewhere. Here is a snippet:

0 notes

Video

Here is a snippet from the audiobook version of mine and Emily van der Nagel’s new book!

0 notes

Video

Snippet of mine and Emily van der Nagel’s new AUDIObook Sex and Social Media

0 notes

Text

How to be a better writer, recommendations for students

People who write for a living, teach writing, or write on writing generally agree that it is hard work. We all have our moments of despair as writers and if we do not, it is quite likely that it is our readers, who despair. William Zinsser, author of “On Writing Well,” reminds us: “if you find that writing is hard, it’s because it is hard. (2012, 9).

I have collected advice from great writing books and resources, focusing on writing nonfiction, writing in academic settings, and most of all - writing clearly. I’ve combined all this advice into 7 big recommendations. (This is not advice on citing and referencing, if you need that, please look here).

The intended audience is MA students. I want to thank the students whose MA and PhD work I am currently supervising, who said “yes” enthusiastically, when I asked them if a set of recommendations on writing would be helpful. Collating this has been very educational and I hope will make me a better writer too.

Most of us write unclearly, because:

- Our thinking is cluttered. To free our writing from clutter, we need to “clear our heads of clutter. Clear thinking becomes clear writing; one can’t exist without the other.” (Zinsser 2012, 8 )

- We read things into our own writing. “Our own writing always seems clearer to us than to our readers, because we read into it what we want them to get out of it. And so instead of revising our writing to meet their needs, we send it off the moment it meets ours.” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 7).

- Very few people realize how badly they write (Zinsser 2012, 17)

1. OUR WRITING IS CLEARER, WHEN WE ARE CAREFUL WITH WORDS.

As William Strunk (2011, np) says: “Omit needless words. Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences.”

Zinsser (2012, 6) agrees, he urges us to get rid of words that serve “no function, every long word that could be a short word, every adverb that carries the same meaning that’s already in the verb, every passive construction that leaves the reader unsure of who is doing what—these are the thousand and one adulterants that weaken the strength of a sentence.

Examples of what to avoid:

- long word that’s no better than the short word: “assistance” (help), “facilitate” (ease), “remainder” (rest), “implement” (do), “attempt” (try), “referred to as” (called) (Zinsser 2012, 15);

- slippery new fad words and jargon (Zinsser 2012, 15);

- word clusters with which we explain how we propose to go about our explaining: “I might add,” “It should be pointed out,” “It is interesting to note.” If you might add, add it. If it should be pointed out, point it out. If it is interesting to note, make it interesting. Don’t inflate what needs no inflating: “with the possible exception of” (except), “due to the fact that” (because), “he totally lacked the ability to” (he couldn’t), “until such time as” (until), “for the purpose of” (for). (Zinsser 2012, 15)

- needlessly long formulations: “the question as to whether” (whether), “there is no doubt but that” (no doubt (doubtless)), “used for X purposes” (used for X), “in a hasty manner” (hastily), #”this is a subject which” (this subject), “owing to the fact that” (since (because)), “in spite of the fact that” (though (although)) (Strunk 2011)

- negative statements: ‘He was not very often on time” is weak, “he usually came late” is strong

Verbs

Use active verbs unless there is no comfortable way to get around using a passive verb. (…) “Joe saw him” is strong. “He was seen by Joe” is weak (Zinsser 2012).

When important actions are in verbs, the sentence will seem clear (Williams & Bizup 2014).

For example (from Williams & Bizup 2014, 32):

- Bad: Our lack of data prevented evaluation of UN actions in targeting funds to areas most in need of assistance.

- Good: Because we lacked data, we could not evaluate whether the UN had targeted funds to areas that most needed assistance.

Adverbs

Most adverbs are unnecessary and annoying. Do not choose a verb that has a specific meaning and then add an adverb that carries the same meaning. Don’t tell us that the radio blared loudly; “blare” connotes loudness. (Zinsser 2012)

Adjectives

Most adjectives are unnecessary, the concept is already in the chosen noun. Stop stating the obvious (yellow daffodils and brownish dirt). If you want to make a value judgment about daffodils, choose an adjective like “garish.” If you’re in a part of the country where the dirt is red, feel free to mention the red dirt. Those adjectives would do a job that the noun alone wouldn’t be doing (Zinsser 2012)

General advice on words from William Zinsser (2012):

1. Care about words. Select them carefully, know the nuances of their meaning.

2. Imitate good writing, figure out how good writers (but don't assume that everything that is in a good journal is automatically well written) accomplish writing well. What makes their writing good? (But also be realistic about your skills).

3. Use dictionaries

4. Master the small gradations between words that seem to be synonyms

2. OUR WRITING IS CLEARER, WHEN IT HAS UNITY

According to Zinsser (2012, 37) unity is the anchor of good writing. To keep the reader from straggling off in all directions; and to satisfy the readers’ subconscious need for order, we need to strive for:

• Unity of pronoun

• Unity of tense

• Unity of mood - any tone is acceptable. But don’t mix two or three.

Ask yourself some basic questions before you start (Zinsser 2012, 38):

• In what capacity am I going to address the reader? (Reporter? Provider of information? Teacher? Person with shared experience?)

• Who am I writing for? (Zinsser says you are always writing for yourself, Terri Senft’s great advice has been to pick someone who is your fan or who believes in you, and to write for them).

• What pronoun and tense am I going to use? (The general recommendation is to write from “I” and to use present tense apart from referring to something that clearly happened in the past “The first time I heard the term “affordances” …)

• What style? (Impersonal reportorial? Personal but formal? Personal and casual?)

• What attitude am I going to take toward the material? (Involved? Detached? Judgmental? Ironic? Amused?)

• What one point do I want to make? “Every successful piece of nonfiction should leave the reader with one provocative thought that he or she didn’t have before. Not two thoughts, or five—just one.”

Think small. Decide what corner of your subject you’re going to bite off, and be content to cover it well and stop. This is also a matter of energy and morale. An unwieldy writing task is a drain on your enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is the force that keeps you going and keeps the reader in your grip. (Zinsser 2012, 39)

3. OUR WRITING IS CLEARER, WHEN WE MAKE OUR ARGUMENTS IN CONVERSATION WITH WHAT HAS BEEN SAID BEFORE

Making arguments is hard. A good start is to ask ourselves “what am I trying to say?” and imagine how we would answer the reader, when they ask us “why are you telling me this?”

Surprisingly often we don’t know. We have to look at what we have written and ask: have I said it? Is it clear to someone encountering the subject for the first time? Has fuzz worked its way into the machinery? (Zinsser 2012, 9)

Graff, Birkenstein & Durst (2018, 3) suggest that academic writing is “argumentative”, and to argue well, we need to enter a conversation, summarizing others (“they say”) to set up one’s own argument (“I say”). They call this a “they say, I say” model. It is helpful for discovering what we want to say and then how to say it clearly.

Graff, Birkenstein & Durst (2018, 11 - 12) offer a MASTER TEMPLATE for setting up an argument using the “they say, I say” model, it goes like this:

In recent discussions of …. , a controversial issue has been whether …. . On the one hand, some argue that …… . From this perspective, …… . On the other hand, others argue that ……. In the words of ….. , one of this view’s main proponents, “…...”

According to this view, …… In sum, then, the issue is whether …… or ………. My own view is that ……... Though I concede that …….. I still maintain that ……… For example, ………. Although some might object that …….. I would reply that …….. . The issue is important because ……….

Taking it line by line, this master template first helps you open your text by identifying an issue in some ongoing conversation or debate (“In recent discussions of a controversial issue has been”), and then to map some of the voices in this controversy (by using the “on the one hand / on the other hand” structure). The template then helps you introduce a quotation (“In the words of”), to explain the quotation in your own words (“According to this view”), and—in a new paragraph—to state your own argument (“My own view is that”), to qualify your argument (“Though I concede that”), and then to support your argument with evidence (“For example”). In addition, the template helps you make one of the most crucial moves in argumentative writing, what we call “planting a naysayer in your text,” in which you summarize and then answer a likely objection to your own central claim (“Although it might be objected that, I reply ”). Finally, his template helps you shift between general, over-arching claims (“In sum, then”) and smaller-scale, supporting claims (“For example”). (Graff, Birkenstein & Durst 2018 12).

The template is a learning tools to get you started, not a structure set in stone.

Find more “they say, I say” templates here, here.

Find an academic phrasebank of phrases that help make cautious, critical, classifying, comparing, defining, describing and explaining sentences here.

4. OUR WRITING IS CLEARER, WHEN IT HAS A GOOD INTRODUCTION

Your writing needs to pose “a problem that your readers want to see solved. That problem might, however, be one that your readers don’t yet care—or even know—about. If so, you face a challenge: you must overcome their inclination to ask, So what? And you get just one shot at answering that question: in your introduction. That’s where you must motivate readers to see your problem as theirs.” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 99).

A good introduction “has the three parts that appear in most introductions. Each part has a role in motivating a reader to read on. The parts are these:

Establish a shared context – “That shared context offers historical background, but it might have been a recent event, a common belief, or anything else that reminds readers of what they know, have experienced, or readily accept” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 100)

State the problem

“For readers to think that something is a problem, it must have two parts:

The first part is some condition or situation: terrorism, rising tuition, binge drinking, anything that has the potential to cause trouble.

The second part is the intolerable consequence of that condition, a cost that readers don’t want to pay.”

“You can identify the cost of a problem if you imagine someone asking So what? after you state its condition. Answer So what? and you have found the cost” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 102).

There are practical and conceptual problems, and each motivates readers in a different way.

“A practical problem concerns a condition or situation in the world and demands an action as its solution.” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 102). A practical problem is about what we should do.

“A conceptual problem concerns what we think about something and demands a change in understanding as a solution” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 102). Conceptual problems are about what we should think.”

“The condition of a conceptual problem is always something that we do not know or understand.

The cost of a conceptual problem is not the palpable unhappiness we feel from pain, suffering, and loss; it is the dissatisfaction we feel because we don’t understand something important to us.” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 103)

“Like your readers, you will usually be more motivated by large questions. But limited resources— time, funding, knowledge, skill, pages—may keep you from addressing a large question satisfactorily. So you have to find a question you can answer. When you plan your paper, look for a question that is small enough to answer but is also connected to another question large enough for you and your readers to care about.” (Williams & Bizup 2014, 104)

3. State the solution

To solve a practical problem, you must propose that the reader (or someone) do something to change a condition in the world. To solve a conceptual problem, you must state something the writer wants readers to understand or believe. (Williams & Bizup 2014, 105-106)

5. OUR WRITING IS CLEARER, WHEN WE KEEP IN MIND HOW OUR TEXT SOUNDS

“Also bear in mind, when you’re choosing words and stringing them together, how they sound. This may seem absurd: readers read with their eyes. But in fact they hear what they are reading far more than you realize. Therefore such matters as rhythm and alliteration are vital to every sentence”. (Zinsser 2012, 27)

Basically, it is really useful to read your own writing out loud. It is particularly useful to do so once you have set it aside for a couple of days, so you no longer exactly remember what and how you wanted to say and can, instead, read what you ended up saying.

A simple rule to remember is to alternate between the length of sentences, Zinsser calls this switching up the “gait” at which the sentences move.

“An occasional short sentence can carry a tremendous punch. It stays in the reader’s ear.” (Zinsser 2012, 28)

6. OUR WRITING IS CLEARER, WHEN WE EDIT AND REWRITE. ALL FIRST DRAFTS ARE SHITTY

The best thing you can do for your writing is to give up the idea that anything is good enough after the first draft. It is not, nor should it be. As Anne Lamott writes in a chapter called “Shitty First Drafts” in her book “Bird by Bird” (1994, 21): “Writing is not rapturous. In fact, the only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts.” … “The first draft is a child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and then romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later.”

Thinking of the first draft like this helps overcome writers block, knowing it has the freedom to be bad, incoherent, childish, ridiculous will help you get out the beginnings of what you want to say, in conversation with whom, and why. Then you shape it into an argument and make it clear.

EDITING AND REWRITING

Learn to let go of what you have written. Yes, it was difficult. No it is not, therefore, pure gold. If it helps, psychologically, create a separate file called “leftovers” and paste all the takeouts there instead of deleting them. I used to do that for years.

“Surprisingly often a difficult problem in a sentence can be solved by simply getting rid of it. Unfortunately, this solution is usually the last one that occurs to writers in a jam.” (Zinsser 2012, 58).

“Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it’s where the game is won or lost. That idea is hard to accept. We all have an emotional equity in our first draft; we can’t believe that it wasn’t born perfect. But the odds are close to 100 percent that it wasn’t.” (Zinsser 2012, 59)

Please don’t send your first draft to your supervisor.

7. ARE YOU READY FOR STYLE?

Always prioritize clarity over style. In fact, it might be useful to ask yourself, as William Zinsser does: “Are you ready for style?” It’s fine if you are not.

“First, then, learn to hammer the nails, and if what you build is sturdy and serviceable, take satisfaction in its plain strength. But you will be impatient to find a “style”—to embellish the plain words so that readers will recognize you as someone special. You will reach for gaudy similes and tinseled adjectives, as if “style” were something you could buy at the style store and drape onto your words in bright decorator colors.” (Zinsser 2012, 16)

“Trying to add style is like adding a toupee. At first glance the formerly bald man looks young and even handsome. But at second glance— and with a toupee there’s always a second glance—he doesn’t look quite right. The problem is not that he doesn’t look well groomed; he does, and we can only admire the wigmaker’s skill. The point is that he doesn’t look like himself.” (Zinsser 2012, 17).

If you feel you are ready for style, here is how to do it:

- RELAX, BE YOURSELF

“Readers want the person who is talking to them to sound genuine. Therefore, a fundamental rule is: be yourself. No rule, however, is harder to follow. It requires writers to (…) relax, and (…) have confidence.” (Zinsser 2012, 17).

Because it is so hard to relax, because we feel responsible to make good, interesting arguments that offer solutions to important problems and do so clearly and with style, we tend to tense up when we start to write. Zinsser (ibid) describes what typically happens:

Paragraph 1 is a disaster—a tissue of generalities that seem to have come out of a machine. No person could have written them.

Paragraph 2 isn’t much better.

But Paragraph 3 begins to have a somewhat human quality, and by Paragraph 4 you begin to sound like yourself. You’ve started to relax. It’s amazing how often an editor can throw away the first three or four paragraphs of an article, or even the first few pages, and start with the paragraph where the writer begins to sound like himself or herself. Not only are those first paragraphs impersonal and ornate; they don’t say anything—they are a self-conscious attempt at a fancy prologue. What I’m always looking for as an editor is a sentence that says something like “I’ll never forget the day when I …” I think, “Aha! A person!”

So when you are writing, and when you are editing, stop to read, and see if you can find yourself in any of the prose.

- MOOD CHANGERS

“Learn to alert the reader as soon as possible to any change in mood from the previous sentence. At least a dozen words will do this job for you: “but,” “yet,” “however,” “nevertheless,” “still,” “instead,” “thus,” “therefore,” “meanwhile,” “now,” “later,” “today,” “subsequently” and several more. I can’t overstate how much easier it is for readers to process a sentence if you start with “but” when you’re shifting direction. Or, conversely, how much harder it is if they must wait until the end to realize that you have shifted.” (Zinsser 2012, 54).

And finally “you learn to write by writing. It’s a truism, but what makes it a truism is that it’s true. The only way to learn to write is to force yourself to produce a certain number of words on a regular basis.” (Zinsser 2012, 37)

References

Zinsser, W. (2012). On Writing Well, THE CLASSIC GUIDE TO WRITING NONFICTION 30th Anniversary Edition. Collins.

Graff, G., Birkenstein, C., & Durst, R. (2018). “THEY SAY I SAY” The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing WITH READINGS, 4TH EDITION. New York, London: W.W. NORTON & Company.

Lamott, A. (1994). Bird by Bird, Some Instructions On Writing and Life. New York: Pantheon Books

Williams, J., & Bizup, J. (2014). Style, Lessons in Clarity and Grace, 11TH EDITION. Pearson Education

Further reading:

Becker, H.S. (2007). Writing for Social Scientists How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book, or Article, 2nd Ed, The Universty of Chicago Press Books.

Tufte, V. (2006). Artful Sentences, Syntax as Style, Graphix Pr

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Just realized that the talk I did for the UQ School of Communication and Arts Research Seminar was filmed, and like ... has nice light and stuff. So if you wanna listen to me talk about affordances and situational proprieties and selfies and social media visuality, here’s a link.

#affordances#academic talk#research#social media#social media research#selfie#culture#visual culture

0 notes

Text

What should ‘cultural data analytics’ be?

This is a talk I recently had to give on datafication of culture (or actually on what cultural data analytics a’la Tallinn University could be like). Some of my colleagues thought they would like their students to read this, so posting the text here. Here is the video, and below is the transcript.

https://vimeo.com/bfmuniversity/review/367698058/d509cf6412

I propose discussing cultural data analytics via two broad questions, both of which I have filled with provocations that I hope will allow us to discuss

- the implications and the politics of how we define concepts,

- the power of those definitions shape the disciplinary and methodological space we operate in

- and how that in turn suggests a positive and inclusive vision of cultural data analytics.

I have my own answers to these provocations, but I am hoping that you will have yours, and that the CUDAN team, when assembled, will agree on the shared ones.

The two broad questions are seemingly simple:

How do we define cultural data analytics, given the extensive debates that have surrounded all of the words in this formulation? and

What is it that we want cultural data analytics to be do?

What is culture?

Ok, let’s start from the first big question, what do we mean when we say cultural data analytics. And to be systematic, we need to start with what do we mean, when we say culture.

Culture is according to Raymond Williams “one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language” (Williams 1983, 87). Other scholars are of much the same mind. Some even argue that the term is ‘so overused, that it is better to break it down into its component parts and speak of beliefs, ideas, artifacts, languages, symbols, art, or traditions.

In The Long Revolution, Raymond Williams offered three ways of defining culture:

1 the “ideal” definition, referring to the systems of valuation by means of which groups establish hierarchies, and subsequently judge the worth, of people, places, objects, institutions, and ideas;

2 the “documentary” definition, referring to the whole range of artifacts, both material and immaterial, produced by a group of people;

3 the “social” definition, referring to “a particular” or “whole way of life” i.e., the patterns of thought, conduct, and expression, prevalent among members of a collective.

Relying on the last one, which Williams appropriated from anthropology, John Fiske has argued that for cultural studies culture ‘is neither aesthetic nor humanist in emphasis, but political’. Politics in this case is the practice of living together, and we must be better at it, because, at the risk of sounding melodramatic - the alternative to living together is dying separately.

Methodological implications of how we define culture

Marek Tamm (2016) has suggested in his introduction to the book “How to study culture” that culture is not something that is passively available for researchers to come study it, rather it is constructed in the process of defining and making sense of it. Culture is thus created as an object of study and our definition depends on the disciplinary background of the researcher studying it.

A distinction that has had a strong impact on the study of culture is between culture as practice versus culture as a system of symbols and meanings. The first approach focuses on the processes of meaning making, and perhaps coincides with the definition of culture or cultures as particular ways of life. The second focuses on the more or less stabile forms and codes within the body of what can broadly be called “cultural texts”. Of course, ideally, we want to study culture as both – texts and practices. However, I think keeping this distinction in mind has analytical merit for the discussion at hand, because it highlights not only the methodological, but also the critical or the politico-economic implications that accompany both definitions. Let’s look at these

Critical implications of how we define culture

Culture as a way of life or as a set of everything created by everyone happens - to a disturbing extent - on corporately owned platforms, which are - post what we in my field call the API-apocalypse - closed rather than open for researchers, and make unreliable, difficult partners. They are also, as Jose van Dijck and Tarleton Gillespie (also this) have been saying for about a decade, not neutral intermediaries, but performative and constitutive infrastructures. Social media platforms, but also appstores shape the performance of social acts instead of merely facilitating them. This means that relying on data created and classified by these corporate platforms for making research inferences is quite problematic. Richard Rogers has called this an issue of vanity metrics. The data that corporations create reflects their needs and their version of a way of life, a culture, sociality. Their version is made of likes, follows etc, because those help measure impact and worth within the attention economy that social media has become. It is a partial rendering serving capitalist needs, wherein everyone is a laborer, a consumer or a commodity, often all three at once.

The version of culture as an assemblage of cultural texts, could be seen more as an issue of digitalizing heritage. This brings it its own can of worms, because it basically means participating in the datafication and metadatafication of culture, which as we’ll talk about shortly, is not necessarily a uniformly positive goal. Datafication, is usually conceptualized as the transformation of social action and many other previously unquantifiable aspects of the world into quantified data, which allows real-time tracking and predictive analysis (Mayer- Schoenberger & Cukier, 2013). Datafication, as we’ll shortly discuss in more detail, has a politics.

Basically, how we define culture implicates whether we want to use existing data or create data, which invites a rather different set of methods, and has a rather different set of risks, implications and ethics.

What is data?

Ok, this brings us to our second word in search of a definition. What is data?

Data is a concept that is most tightly linked to empiricism and positivism. We answer empirical questions by obtaining direct, observable information from the world. That direct observable information, often conceptualized as discrete units of information, is what is called data. Once we verify data, we get, from the positivist perspective - facts.

However, this only seems straightforward. Just like the definition of culture emerges out of and depends on the process of defining it, so is data made and not found. As Geoffry Bowker has famously said: “Raw data is both an oxymoron and a bad idea; to the contrary, data should be cooked with care (2005, p. 183-184). Lisa Gitelman and Virginia Jackson (2013) propose that the seductive power of the term raw data lies in it echoing a presumption that data come before fact, which suggests that data are the starting point for what we know, and that hence data must be transparent or objective.

Data as a thing, data as ideology

My friend and mentor prof. Annette Markham has argued (2016) that in academic discourse data operates on at least two levels – as a thing and as an ideology, both of which obscure the fact that data is not where meaning resides.

She argues that speaking of data as a thing is an ideological stance, which leads us to focus our attention on the wrong part of the process, we focus on what remains after we tidy, clean, condense and simplify and invites us to focus on pieces of text, or outcomes of interaction, distracting us from the point that this is not where meaning resides. Meaning, arguably, resides in the interaction not the outcome of the interaction, it resides in the making and consuming of the text, not in the text itself.

This doesn’t mean that data is useless, or we should not try to make data, it rather means that just as we need to be clear on what culture means for CUDAN, we need to be clear on how we cook data in this project. What tools do we make or use, and how do these tools function as frames or filters. Because tools carry the epistemic traditions they derive from (cf. this by Eef Masson, 2017) and most, if not all of the analytics tools used to study culture today were built by empiricists and positivists. To make this point clearer, I invite us to think about data through metaphors

Data metaphors

You have probably all seen and heard a version of “data is the new …”

Cornelius Puschmann and Jean Burgess suggest that there are metaphors of data as a natural force to be controlled (so here there are a lot of oil and water metaphors) and metaphors of data as a resource to be consumed (where they place food and fuel metaphors).

Metaphor scholars (Lakoff and Johnson 1980) have been saying for decades that metaphors function conceptually to not only reflect but to construct our experience of reality. If we say “data is the new oil” the comparison of terms builds or promotes a particular meaning. The term being defined (data) is connected to the supposedly more known term (oil). So if we think of petroleum oil then we think of it having to be drilled, which is dangerous to do, we think that world economies depend on it, that finding it unexpectedly will make you very rich, that you can make anything from it. If the comparison sticks, and everyone starts calling data the new oil, as they kind of have, it will work under the surface not only to reflect, but to influence how we think about data.

As Luke Stark and Anna Lauren Hoffman recently argued, the data metaphors, in particular the oil metaphor, invites specific data practices and specific approaches to data ethics. Liquid metaphors of data lakes, data oceans, data floods and data tsunamis tend to “forestall ethical or regulatory interventions by positioning data as uncontrollable” (Lupton 2013). But Stark and Hoffman also propose that we can look to common data metaphors to solve some of the regulatory and ethical problems we’re having with internet intermediaries abusing our data. If data is a natural resource, then perhaps we need to borrow from the ethical codes of forestry and think of data stewardship. If we think of personal data as of personal digital remains, maybe we need to borrow from morticians or doctors, and think of data care or data fiduciaries - fiduciary duty is the legal obligation of one party to act in the best interest of another.

Again, for the talk at hand, I want to ask – what kind of a data metaphor do we at Tallinn University want to operate with? Should we be satisfied with pre-existing metaphors, and live with what they illuminate and obscure about the world?

Methodological implications of how we define data

Something we hear repeated so often, is that the volume, velocity and variability of ‘big’ data has transformed how social research is conducted. More interestingly, it impacts what we think we are doing when we conduct said research. This, I think is the biggest methodological implication of how we define data. Do we think we’re cooking it? And what do we think it means if we’re cooking it? Some of my colleagues have noted a dangerous erosion of the role and meaning of interpretation in “data-driven” research (Markham 2016). If we agree that there is an erosion, and if we agree that reducing phenomena to data involves classification, which in turn obscures ambiguity and contradiction (Gitleman and Jackson, 2013), and if we think ambiguity and contradiction are important when speaking of and for cultures, then we need to think of how to bring them back. One option is to try to imagine an interpretivist data analytics.

Interpretivism rejects the view that meaning resides within the world independently of how people and groups interpret it. Typically, interpretivists advocate for context, which often means asking people things. This might not always be possible or wise with the types of projects we are imagining for CUDAN. However, the idea of context sensitivity or thick descriptions has been utilized in the more recent discussions on whether we can and should thicken our data.

Latzko-Tith, Bonneau and Millette (2017) say that thickening data means supplementing data with richly textured information, in other words, adding layers to them. Thick data is coated with several layers of rich metadata and paradata, so it is like an onion. Instead of points, thick data are whole little structured worlds. But we can think of thickening data also in terms of being more creative with what counts as data or what kinds of data we have, want, what we discard when we clean it, do we clean all of it, etc. My own experience working with data scraped from the Instagram API and Twitter API have highlighted this on a very personal level. Thickening or layering 90 000 image posts or 25 000 tweets with anything other than the metadata that the platform provides may seem impossible. But computational tools can also show you that the 90 000 images are from 180 accounts, or that in the 25 000 tweets include only 520 heterogenous ones that have been retweeted even once, which makes space for layering based on the computational power of the human brain. Basically, the argument is that layering embodies what interpretivism has learned from hermeneutics, the circular way of working a chunk of data and its context.

The critical (political-economic) implications of how we define data

Now, depending on how CUDAN decides to define data and go about cooking it will situate it at more or less problematic end of the spectrum of what can be called the political-economy of datafication. One of the best questions I heard two weeks ago at the AoIR conference in a methods session, was: “What evil things could be done with these new insights you have generated?” So, I think it is important that we too contemplate what evil things can be done with CUDAN, and what version of the datafication of culture and life we want to contribute to.

Many professionals and scholars see datafication as a revolutionary research opportunity to investigate human conduct. But, datafication is also heavily critiqued. A very poignant recent critique comes from Jathan Sadowski (2019), who recently published an elegant analysis of data as capital (as opposed to data as a commodity, which other work has done).

Sadowski argues that like social and cultural capital, data capital is convertible, in certain conditions, to economic capital. It adds new sources of value and new tools for accumulation. It also currently guarantees that those who already have a lot of this capital, like GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) or BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent), will accumulate more, and those who don’t have it, are unlikely to amass any significant amounts of it.

Looking at data as capital allows him to notice that the data imperative, or the drive to accumulate all and any data from all sources, by all means possible, now propels how business is done and how governance is enacted. This means a total datafication of everything, by subjecting previously non-commodified and non-monetized parts of life to the logic of datafication and colonizing new spheres of life or new places in the world, so they can become sites of data extraction. So decisions like buying a company or launching a service are increasingly made for data potential, not because of revenue. Google gives primary school studenst free laptops or invests in healthcare or hosts all of Tallinn University’s emails and documents not because it cares, but because it is already or will very soon profit from all of that data. Extraction of data – and Sadowski is specific about calling it extraction and not collection or even mining, because calling it extraction highlights the exploitative nature of dataveillance, where data is taken without meaningful consent or fair compensation - is a core component of political economy in the 21st century.

What is cultural data?

Ok so this brings us to the end of the prompts and provocations around definitions, and implores us to ask what we mean when we say ‘cultural data’ and through addressing the methodological implications of defining cultural data – what we mean by cultural data analytics

That the computational processes of sorting and classifying people, places, objects and ideas have profoundly altered the way ‘culture’, as a category of experience, is practiced, experienced and understood, is something that many authors have addressed (Striphas 2015, Andrejevic, Hearn and Kennedy 2015). So, the question is - is there any other way to define cultural data than as the process and outcomes of the datafication of culture. And if there is none, then the question becomes, is there a way to shape how datafication of culture happens or to imagine alternative ways of datafying culture, because what we have now, is consolidation of the work of culture into the hands of a few powerful corporations, which, if we believe Ted Striphas, will lead to “the gradual abandonment of culture’s publicness”

Methodological and critical implications of how we define cultural data

If cultural data is the process and the outcomes of the datafication of culture, which is currently to a large extent governed by corporations for corporate interests, then this invites another question for CUDAN -

Do we need to come up with so called alt metrics for understanding culture? And what would those be?

I mentioned Richard Rogers (2018) work in the beginning of this talk. He proposes metrics that do not build on social media as a vanity space, but as one for social issue work. He calls them critical analytics. We can basically treat the past 15 years of social media as a case study for why we can’t rely on the metadata and the datafication models that corporations have created for their own needs, because analyzing those creates a particularly tilted view of the studied phenomena and makes CUDAN contribute to instead of subvert what is arguably currently wrong with the datafication of culture.

Epistemology of cultural data analytics

This definition work quite neatly introduces a bigger issue, which is what kinds of ontological, epistemological and axiological premises do we want cultural data analytics to have? We’ve talked earlier about bringing a certain interpretivist sensibility to data analytics, at least to our methods of cooking data, but I’m not sure we necessarily want to situate CUDAN fully in interpretivism. We also don’t want to situate it in what Christian Fuchs (2017) calls digital positivism, which he says does not connect “statistical and computational research results to a broader analysis of human meanings, interpretations, experiences, attitudes, moral values, ethical dilemmas, uses, contradictions and macro-sociological implications. And which he says means that it is just what Paul Lazarsfeld called administrative research predominantly concerned with how to make technologies and administration more efficient and effective.”

Instead, I would suggest, and Fuchs suggests, and frankly most authors who have studied social media for many years are suggesting a critical theoretical alternative. What does that mean?

What is it that we want to accomplish?

Ok this finally brings us to the second big question, which is, what do we want cultural data analytics to do? If we want to build critical cultural data analytics, then whatever else we want it to do, we will want it to challenge dominant assumptions and, ideally, change the world towards a better place. No pressure, right?

Looking across various academic, corporate and strategy documents big data analytics and cultural data is imagined to promise the following:

data analytics in general seems to promise to:

help us gain unprecedented insight into stuff –like public opinion, behavior patterns and relationships.

build a more ‘productive and intuitive’ user/consumer experience.

overall, there are a lot of vague but optimistic promises that we can do research that doesn’t exist yet, ask questions that do not exist yet, open up new avenues for inquiry

Within the realm of cultural analytics and digital humanities more broadly, the promises seem to be that we can:

digitally preserve and share cultural heritage. Which:

allows new discoveries that will transform our understanding of our cultures, identities, heritage and history.

make sure these cultures do not disappear;

make sure the heritage industry is relevant in the digital age

allow cultural differences and commonalities to be explored.

shed light on human history and the relationships between cultural and geographic areas.

Help us understand the dissemination of ideas and cultural phenomena and,

in relevant cases (such as in art fairs, universal exhibitions, or Olympic games), improve the management of current events.

introduce data-driven decision-making in the cultural sector (how to do this without adding to the accumulation of privilege and disadvantages, inequality, discrimination etc

provide arguments for the provision and allocation of public funding and measurement of its impact

Frankly, most of these do not sound like critical ambition. Some of these sound outright administrative, many descriptive, some interpretative.

So, again, the question for CUDAN is – which goals do we want to set for our version of cultural data analytics.

Do we want to say that cultural data analytics will help us understand culture better?

Does that mean that we think that the ways in which we understand it now are not good enough? And I am looking at Marek Tamm who has recently edited a whole volume on this. So, you know, provocatively I ask, what’s wrong with those ways of understanding culture? Did you know that training creating just one AI model for natural-language processing can emit as much as 600,000 pounds of carbon dioxide? (Strubell, Ganesh and McCallum 2019

via this). That’s about the same amount produced by 125 roundtrip flights between New York and Beijing. How can we make sure that cultural data analytics is better enough than the more eco-friendly alternatives to be worth it?

Do we want to say that cultural data analytics will be more efficient in understanding culture? That it will create more actionable insights both for researchers and for policy makers? That it will release us from the chains of stepping on the same rake and making the same mistakes?

That, in and of itself, is a great goal. Sheila Jasanoff has suggested that actionable data can problematize the taken-for-granted order of society by pointing to questions or imbalances that can be corrected or rectified, or simply better understood, through systematic compilations of occurrences, frequencies, distributions, or correlations. She speaks specifically of the power of the compilations of climate data, but surely this could be a great asset in the cultural sector as well.

Then again, here too, we can ask what that costs. Another example - AMS, Austria’s employment agency, is about to roll out a sorting algorithm built to increase efficiency. They ran statistical regressions to find out which factors were best at predicting an individual’s chances of finding a job. So they can stop giving support to those who are less likely to find a job. Like women and disabled people. The algorithm increases efficiency and offers highly actionable insights, as it ensures that the agency does not waste resources on giving support to people who will not, in the end, benefit from it. How can we make sure we don’t build this type of efficiency?

What should cultural data analytics be?

Ok so, lets reiterate. I presume that everyone’s answer to what cultural data analytics should be is different, and that is the point of asking these questions and raising these provocations, but let me clarify my take on it and offer some quick examples.

1. I think that while in abstract it makes sense to think of culture as both a practice and a set of texts, it is always also political in emphasis. I also think CUDAN would possibly benefit from a narrower definition of culture, or at least assigning different narrower definitions of culture to specific subprojects. What I’m trying to say is that it is not enough, and perhaps it is even a bad idea to try to combine what is usually called social analytics, i.e. analytics of the trace data cooked on and by GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facbook, Apple) or BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) platforms and what is usually called digital humanities, i.e. analytics of digitalized cultural heritage data, and call it cultural data analytics. I don’t think that this is the innovation we’re looking for. My work in social media allows me to see the problematic aspects making inferences of platform data, but it also makes me weary at the ambition to turn cultural heritage data into platform ready data. I think combining these two will keep us stuck in the social media logic that has or will soon colonize all our data, so true innovation lies in coming up with alternatives. This is, of course, easier said than done. If we do want to engage with the “existing” data people generate on the platforms, then I do think that instead of using their data as evidence of practices or ways of life, we should critically analyze infrastructures.

Let me offer an example - Nic Carah and Dan Angus (2018) at University of Queensland are, working on a project that they call “critical simulations”. They engineer and scrutinize how Instagram’s algorithms process, classify and make judgements about cultural life. So they are trying to build the infrastructure to critically analyze it.

2. I think CUDAN needs to be adamant that it is cooking data, and careful in who elses cooking it consumes, as well as who it cooks for, and whom it cooks for for free (and this invites an open data discussion, which I didn’t have tome to go into, but we can in the Q & A). This means that we should set aside resources towards critical tinkering with existing tools, invention of new ones, a reimagination of metrics.

Let me offer another example. Trevor Paglen and Kate Crawford recently organized an artistic intervention called ImageNetRoulette (look here). Image Net is a huge database of photographs that is broadly used to train AI systems in how to recognize, categorize and classify. It is one of the more widely used training sets for machine reading. Among the 14 million images ImageNet was trained on, there were images of people that were sorted manually by humans like Amazon Turkers. They categorized what they saw based on their own biases, and their biases ended up in the algorithm. So while it is easy to imagine a cultural data analytics project that just uses an existing tool to generate some sort of a semi metaphorical rendering of what people represent on social media, ImageNetRoulette was conceived to expose the biases and politics behind the datasets and thus the AI that classifies humans. The project was hugely popular and made its point elegantly. People were labeled in racist, sexist, misogynist and otherwise judgmental terms. And it has already had an impact, the researchers behind ImageNet promised to delete more than half of the 1.2 million “people” images from the dataset.

3. I think CUDAN needs to be ambitious, but profoundly critical in setting goals, to avoid digital positivism, administrative research at the service of efficiency, as well as artsy vanity projects with limited social impact. I think it needs to commit to impact and data justice.

Pitting research questions or interests against each other is problematic, and I am not trying to suggest that everyone needs to study populism, climate change or alternatives to the particular version of capitalism we have, but maybe we should. At least in some way. Is there way to make a project about Estonian heritage cultures to be about the current debates surrounding Estonian forests. Is there a way to simulate and critique and then productively build alternatives to existing infratructures or data logics? In social media research datafication, appification and platformization have become almost curse words, yet in what I have read about the digitalization of cultural heritage, we seem to be hardly able to wait before everything is an app.

I feel like CUDAN has a decision to make. What kind of a project does it want to be. Critical? Descriptive? Computational? Administrative? I don’t think it can be all in equal measures. But I am very excited about the idea of a truly critical, contextual and ethical version of data analytics.

Does it exist? No. Can it be built? I believe so. Maybe this will be CUDANs gift to the world.

0 notes

Text

My speculative-fiction-based provocation for the AoIR 2019 “fuck the system” roundtable

I did a talk in a panel re: the Tumblr NSFW ban (which I’ll post later) and participated in this roundtable at my most beloved conference - AoIR2019 this year. Both were fun and led to amazing conversations, but “Fuck the System” was particularly awesome, because it was incredibly well attended, and included so many interesting comments and contributions not just from the speakers, but also from the audience (the pic is about half of the room doing their version of ‘fuck the system’).

My amazing colleague and co-author Emily van der Nagel created a great twitter thread from the round table, which the Thread Reader App unrolled for everyone’s reading pleasure.

Anyway, here is my provocation.

Like many of us, I was very frustrated with Tumblr’s choices in December of 2018. So I thought that it might be worth engaging in some speculative fiction thinking on what social media would be like if it did not try to deplatform sex every time someone pointed out a platform has a nazi problem. Because it really seems kind of Pavlovian by now – we say: “hey, uh … you have these people advocating for hatred or genocide.” And they say: “titties, titties, omg I saw nipples, THINK OF THE CHILDREN!” It’s kind of the inverse of that old movie Wag the Dog. Instead of faking a war to cover up a sex scandal, social media platforms seem to be faking a sex scandal every time they need to cover up how their platforms are used for disseminating hate.

Speculative fiction builds on approaches like socio literary techniques, speculative design, design fiction, creative prototyping, speculative science fictions etc. (i.e. Future oriented methods of Donna Haraway and Bruno Latour.

Speculative science fiction (Annette Markham and Kseniia Kalugina, 2017)

Design fiction and creative prototyping techniques (Burnam Fink 2015)

‘socio-literary techniques’ (Bennett & Clark Miller, 2008)). These are methods for harnessing socio-literary imagination, and they sometimes work with prompts developed from existing knowledge and literature. I too came up with prompts:

First I asked some of my Facebook friends to fill out a Facebook profile for someone who would post sexually explicit content on Facebook

Second, I asked some of my friends, who are at least hobby level creative writers, to imagine that all sexual content has been banned everywhere on the internet for 10 years, and then to write me a short vignette from the perspective of a content moderation AI, a sexdoll, a priest, etc, there was a whole list

Based on this, I want to briefly go through the imaginaries about Facebook with sex, the whole internet without sex, and Tumblr with and without sex, and see where we end up, provocation wise.

Let’s start with the Facebook profiles. It seemed that people thought that it would be either:

young, kind of ditsy, not very career-oriented women, who are into nightlife, witchcraft, Charli XCX and 24-hour champagne diet”

completely nondescript successful men

or these incel-y young men, who have 73 Reddit profiles and post 4 different kinds of anti feminist quotes who would post sexual content on Facebook.

That was very brief, but let’s move to the narratives.

I had a story from the POV of a priest, a 50 year old woman, a 50 year old man, and a sex doll in a post internet sex ban world. Here’s what I picked out from these:

The priest story communicated...

... certain relief to be able to live in the world where a celebrity boob selfie is not going to commandeer attention.

... worry that life without flirting on Facebook would be sad - and the presumption that not being able to post sexual content on the internet also means no flirting is interesting here

... Finally, this story ended with a question: “But is a cat sad to be castrated?” – which tells us that an internet with no sexual content equals castration.

The 50 year old woman POV story painted a very evocative picture of going in circles and how rhetorical leaps are made by those governing our internet. I think my favorite part of this story was how the author linked declaring young women’s exposed bodies on social media explicit content with the feeling she had when she was “young, and full of uncomfortableness with your own body” until she gathered up her guts to take off her bikini and swim naked and laugh

The 50 year old man POV story, I think, was perhaps the most surprising for me. In it the protagonist tells a story of how he remembers masturbating furiously all night before the ban went into effect, and how hard it was for him to get off or get or keep an erection for months after the ban. But then spring came, women wore yoga pants, so all he needed to do now was to sit on his window, stare and masturbate. During summers he went to the beach, and during winters he just had to recollect a mental image from the summer. So basically the porn ban made him a raging peeping tom.

Finally the sex doll POV story told a tale of a male owner, who used scream at her and pull her hair, but since the ban of sexual content on the internet, he has been getting calmer and gentler. Just rubbing his finger over her nipples makes him sigh happily. He has named the doll Helena and likes sleeping with it. “I think he loves me” the story ends.

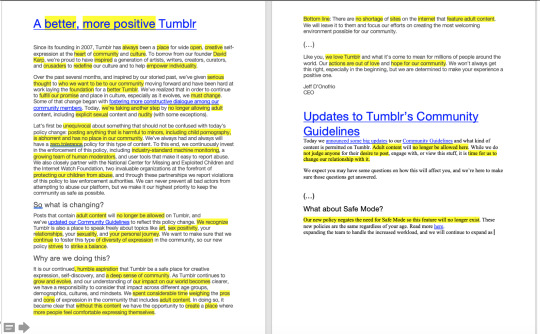

Ok, so let’s now look at Tumblr CEOs blog post about the NSFW ban. He says, multiple times, that they have thought really super very hard about it and Tumblr with sex is:

not positive

does not have deep sense of community

does not feel like a safe space for creative expression and self-discovery

and makes it impossible for Tumblr to fulfill their “promise and place in the culture”, to “grow” and “evolve”, to “have an impact on the world”, and to create a place where more people want to express themselves.

It is unclear what these big promises are that Tumblr feels it has made to “the culture” or what impact it is planning to have on the world.

The updated community guidelines, however, assure us, that throwing sex out of the window “negates the need for Safe Mode.” When there was porn you could at least opt out of seeing it, but everyone must see the hateful content that remains on the platform.

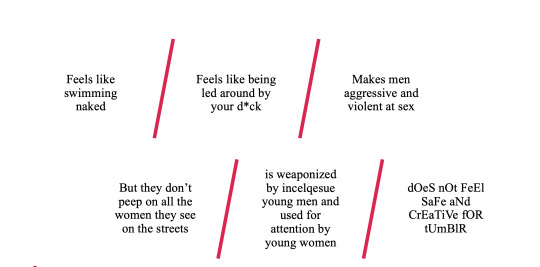

So putting all of this together, and trying to imagine social media WITH sex, we get this bizarre, but not entirely useless picture, which I hope can be used to start more conversations or ask consequent research questions.

Sex on social media, according to this speculative fiction exercise, is:

like being able to swim naked and laugh

like being led around by your dick - uncomfortable, but you’d rather keep it than be castrated

keeps men from stalking and peeping on women on the streets

but also trains men to be really aggressive and rough at sex

allows young women to get attention, and they like it

men just like it

young incel men weaponize it

but it makes tumblr feel really unsafe and doesn’t allow it to fulfill their huge promise towards the future of Culture.

#AoIR2019#speculative fiction#socio literary methods#speculative methods#roundtable#deplatforming of sex

0 notes

Photo

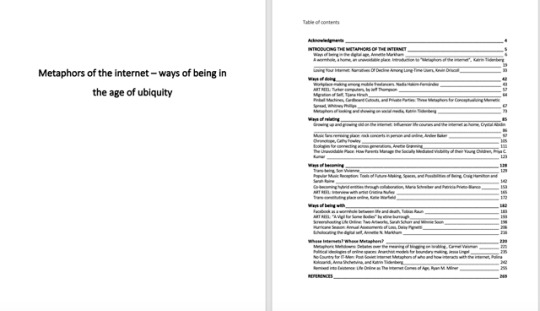

Dotting the i-s as I am about to get on all the planes to fly to AoIR (yay! Also will post later re: what I’ll be presenting on and what I’ll be speaking about a week later at UQ).

The i-dotting included some clarifications for the publisher as they are getting ready to send our epic curated collection "Metaphors of the internet - ways of being in the age of ubiquity" into production. My beloved Annette Markham and I, and our 27 amazing collaborators have been working on this for about two years, and a couple of weeks ago, we finally submitted! We are super happy with the result, super impressed with and proud of the authors, and super pleased that it found a home in the Digital Formations Series at Peter Lang. This book is packed with lived experience and varied modes of finding and expressing meaning about an internet that continues to be viscerally relevant, even when it is ubiquitous or seems to be disappearing. We have images, vignettes, poetry, dialogues, essays and analytical chapters.

#new book#curated collection#metaphors#metaphors of the internet#ubiquitous internet#thick descriptions

0 notes

Text

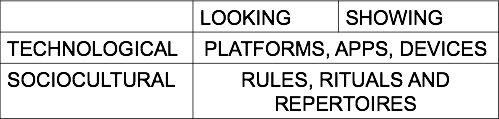

Showing and Looking

This is my talk from Digital Subjectivity and Mediated Intimacies at Coventry last week. People said they’d like to have access to it, and I’m not sure if I have the juice to turn it into An Actual Academic Publication rn, so here it is, as is, for now. It approaches visuality via concepts of affordances and situational proprieties, offers a set of 7 high level affordances social media has for showing and looking, uses the metaphor or horizon and foxes, which gave people many feelings at the time, and is overall entirely too tl:dr for a blog post, because it was a 45 min talk.

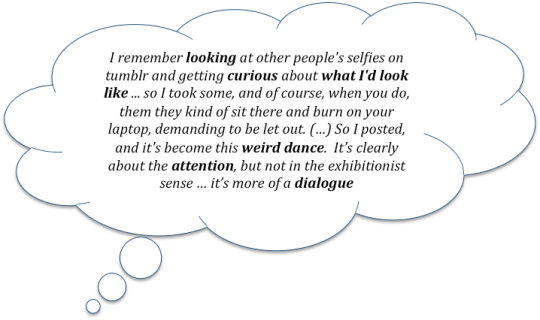

Looking and Showing with Social Media

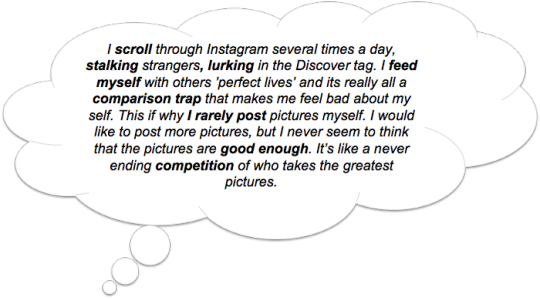

Over the past seven years, I’ve studied different social media platforms and apps, different groups of people and different types of visual content through different research projects. In some cases I have only had access to people’s self-presentations on the internet – for example I did a study about how Russian and English speaking pregnant women present themselves and construct pregnancy on Instagram, or a another about how aging femininity is performed on Instagram. In other cases, I had access to people’s perceptions of their experiences and motivations. This was the case in a large project that I did with Annette Markham, where we taught young people to be the ethnographers of their own digital experiences, and then in return they shared with us their fieldnotes and braindumps. This was also in the case of a long term ethnography with sex bloggers on Tumblr, where I talked to people again and again, and they said a lot of interesting things, like:

I am drawn to whether there are any discernable patterns in how people behave, how they make sense of what they are doing, and how those are immanent to discourses, norms and power hierarchies. This means that in the context of social media and visuality, I am interested in what people are doing, but also in what else they are doing, when they are - for example - posting, or liking, or hating on selfies; when they use a reaction gifs, because they want to tell someone to ‘F*** off,’ but feel they can’t, because as women on the internet, they’d be deemed hysterical.

Now, what does it even mean to say that I am interested in visual practices and power hierarchies? How do we define visuality here, or power? How are they linked? Depending on who you read, power can be defined as something one has, something one keeps from others, or as something akin to a broad interpretational repertoire of a group or a society. Max Weber defined power as “the ability of an individual or group to achieve their own goals or aims when others are trying to prevent them from realizing them.” So it is quite antagonistic. A Marxist framework relies on the presumption that there is a limited amount of power in the society, and it can be held by only one group at the time.

Foucault has given us perhaps one of the more popular theories of power today by pointing out that power is everywhere’, it is enacted via discourse. For Foucault power is productive, he doesn’t define it via those who lack it or via the ability to keep something from someone, or coerce someone to do something. In Foucaultian terms, power is less something that someone has and uses, and more something that is discursively constituted and that then, constitutes its agents or subjects. He used the term ‘power/knowledge’ to signify that power is constituted through accepted forms of knowledge and ‘truths.’ So in this sense we can look at socially mediate visuality and ask what kinds of truths it reproduces and is constituted by. And while not all social media visuality is photographic, a lot of it is, and photography has its own historically established ‘special relationship’ with truthfulness.

But, visuality, as it is often is defined, seems to presume a certain preoccupation with power. In my Selfie book, I collated a bunch of definitions of visuality and ended up with “visuality can be thought of as a historically and culturally specific way of seeing. It is inherently political as it shapes and constrains what we think is possible to see, what we are allowed to see, made to see, what is worth seeing and what is unseen. Sometimes scholars will talk about different regimes of visuality, which indicate that there are competing sets of norms, values and hierarchies that guide what can be and is seen.” So I guess, we can just say that we are interested in a particular mode, practice or repertoire of visuality in the realm of social media, and that presumes that we’re alert to the power relations involved.

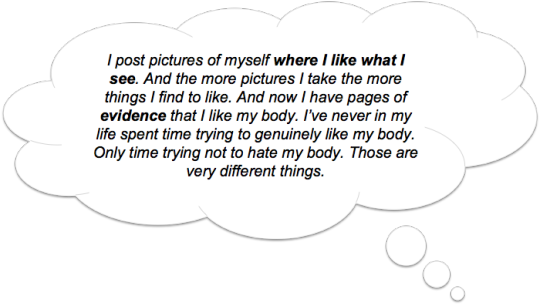

In this light, what I wanted to do today, was to bring together all of my different empirical projects about visual social media practices, and to try and say something hopefully interesting about two repertoires of social media visuality - LOOKING and SHOWING.

I say looking, and not seeing purposefully here. For today’s argument’s sake I want to ignore the broader, automatically functioning visual perception, and focus more on looking, which includes noticing. Noticing here being the culturally learned way in which we organize what we see.

As John Berger said, we only see what we look at, so to look is an act of choice. He also said that looking is quickly followed by our awareness of being seen, for the "eye of the other" combines with "our own eyes to make it fully credible that we are part of the visible world.” For him, vision is more reciprocal than of spoken dialogue. One could argue that this is basically a symbolic interactionist statement, which we can trace back to the theory of the looking-glass-self from 1902. Cooley, Mead and later Goffman were talking about this reciprocity in terms of actual and imagined co-presence, self presentation, impression management and identity, but the point remains - we look, but we are also aware of, or presume we are being looked at, which leads us to start showing (and not just being seen).

So I am interested in these agential, at least partially cognizant practices of looking, or choosing to see, and showing, or choosing to be seen, and how those constitute and are constituted by powerful discourses of social order or regimes of truth.

Ok. Well, what are we to make of social media looking and social media showing, when people seem to have rather contradictory experiences with it? For example on of my participants said:

Here, showing, being looked at are a matter of self reflection, affirmation and an introspective project of the self, which then altering how one looks at oneself

But then another one said:

So here we get being looked at as someone, as belonging to a group of people, women in this case, who are being looked in a particular way, in a sexualized, objectifying way, and instead of self reflection and repair we have sexual arousal.