Text

I’m Moving!

This Tumblr will no longer be maintained -- BUT it’s been recreated as a Substack, also called Jason Fry’s Dorkery.

I don’t have any plans for subscriptions etc. right now, but I’m hoping the change of scenery will inspire more frequent posting about my various geeky endeavors.

Anyway, I’m now at https://jasonfry.substack.com/. I’d be honored if you joined me over there, and thanks so much for reading here over the last 10 (???!!!) years.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’ve fallen behind on a winter’s worth of Movies Everybody’s Seen But Me and now it’s baseball season again, so some overdue capsule reviews....

Dark Victory (1939)

A melodrama about Bette Davis as a young socialite diagnosed with brain cancer, with no hope for a cure -- “prognosis negative,” as she spits in one key scene. Loses its footing at the end, with a simultaneously idyllic and faintly ridiculous switch to Vermont and Davis dying accompanied by a yowling celestial choir. Humphrey Bogart is miscast as an ambitious horse trainer but Davis is terrific, blasting defiance at all and sundry, fate most of all. Bonus: Ronald Reagan doing good work as a bilious, rich sometimes-do-well.

Dark of the Sun (1968)

Rod Taylor and Jim Brown share the screen as mercenaries hired by Congo’s president to save a town of European miners from a rebel incursion. Grim and considered horrifically gory for its time, it’s definitely uneven, but a few set pieces -- such as Taylor battling a former Nazi with chainsaws and the horrors of night in the rebel-held town -- will stay with you.

Charade (1963)

Often called the best Hitchcock movie not directed by Hitchcock (it’s Stanley Donen’s work), and it’s easy to see why. Stylish throughout and wonderfully funny at times, with George Kennedy and James Coburn stealing the show as villains, but so fizzy that it ultimately floats away. And once again, Audrey Hepburn gets shackled with a leading man old enough to be her father. This time at least it’s Cary Grant, but it’s still gross.

Badlands (1973)

Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek carve a murderous trail across the Great Plains in a retelling of the Starkweather spree. Both are terrific, with Spacek’s flat, affectless voiceovers particularly chilling. Ripped off repeatedly in the decades since its release, with True Romance a particular offender -- it even nicks the music.

All the King’s Men (1949)

Anchored by a towering performance by character actor Broderick Crawford, who gives Willie Stark a poisonous, rotten charisma that’s equal parts riveting and repellent. Stark is based on Huey Long, but his grip on the mob that sees him as a messiah feels very of the moment. Mercedes McCambridge is wonderful, as always, as a political operative fairly boiling with resentment and cynicism. And the movie feels very modern, with documentary-style cinematography and jarring cuts. But all that’s good about it -- which is a lot -- gets undercut by its melodramatic excesses and flights of purple dialogue.

Death in Venice (1971)

Too arty for my tastes, and most of it’s set on the Lido, which isn’t the filmmakers’ fault but still feels like cheating.

The Lady From Shanghai (1947)

Another Orson Welles film taken away from him and recut, which much of the footage lost and what might have been much lamented by film fans. Welles isn’t particularly believable as an Irish sailor and there are few if any characters you root for, but after a few minutes in her presence you’d kill for Rita Hayworth too. The movie is always fascinating to look at, with the camera never quite where you expect it, and the scenes on the yacht are suffocating and disturbing, as Welles tries to escape the traps set by him by his employer and his associates.

The Man Who Came to Dinner (1942)

Slight but entertaining, with Monty Woolley having a grand time merrily chewing several films’ worth of scenery. He’s worth the price of admission even if the rest of the movie fades fairly quickly from memory.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

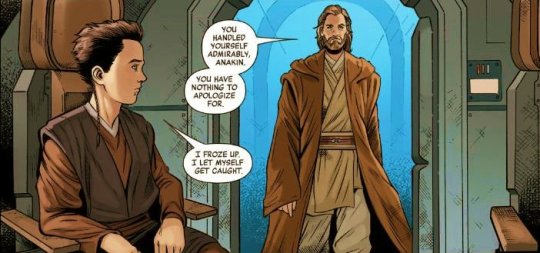

I’d forgotten about this nice moment from the comics....

HEY, COOL, SO I’M CRYING ABOUT OBI-WAN KENOBI AND ANAKIN SKYWALKER AGAIN.

This is such a fascinating look at their dynamic when Anakin was younger, that Anakin is clearly boiling with frustration and Obi-Wan’s reaction is to give him leeway, to understand that he’s working on it, that nobody’s perfect and nobody expects Anakin to be a perfect Jedi, but he’s getting there. Obi-Wan praises Anakin several times in this issue alone and, when Anakin has an outburst at him, the whole, “You never wanted me!” thing, Obi-Wan is hurt and concerned about this, so he makes sure Anakin knows he’s wanted.

He gives Anakin space for a couple of hours, lets him cool down because Anakin needs that breathing room for a bit, then trusts him when they land on the planet and helps save himself from the pirates. He gives him an important job to do, he trusts Anakin to use his training to help, and then he sits down with Anakin, gently and warmly explains to him that Obi-Wan felt like Anakin would be the one who didn’t want him.

Obi-Wan makes himself vulnerable with Anakin, shows that he has worries and fears as well, that if he couldn’t save Qui-Gon, someone who could already take care of himself, how can he save someone who’s just learning? But that’s the whole point–Obi-Wan listens when he needs to, understands that he needs to understand himself just as much as he needs to understand Anakin, that this struggle is just as much for him as it is for Anakin. That he doesn’t hate himself or rip himself to shreds over this, because Obi-Wan’s emotional foundations are the bedrock of all good (THANKS AGAIN FOR THAT QUOTE, “MASTER & APPRENTICE”) and he’s so incredibly emotionally stable that he can take stock of himself and Anakin both, that he can look outside his own feelings, that he can know himself and recognize when he falls into perfectly understandable and human pitfalls, that he can recognize that Jedi wisdom is:

(The Last Jedi novelization by Jason Fry)

This is why I will always defend Obi-Wan as a teacher, because he makes sure to talk to Anakin, to show that he understands maybe not everything of what Anakin’s going through but still a lot of it, Obi-Wan doesn’t chastise him for being moody or misunderstanding, instead he praises Anakin when he does well, offers him things he knows Anakin will like, and makes them a team. Yes, sometimes he gets frustrated, yes, sometimes Anakin oversteps his bounds and will continue to do so long beyond when he should have learned more control over himself, but even then Obi-Wan makes sure to ask how Anakin’s doing (asks about Anakin’s dreams in AOTC, until Anakin changes the subject on him), he makes sure to joke and laugh with him (when Anakin is panicking in the lift, Obi-Wan jokes with him to calm him down, and it works), he makes sure to tell Anakin things that will make him happy (points out that Padme was glad to see them, when Anakin was getting upset that she didn’t seem to care).

This entire issue really seemed to be keeping Attack of the Clones in mind, that Anakin has trouble with not being ahead of where he’s ready to be, that he’s teetering between being ready and not ready to come along on a mission here, that he’s teetering between being ready and not ready to be on his own during AOTC, that Anakin is champing at the bit at 19 to be allowed to go beyond their mandate and to be seen as a big shot before he’s ready, that Anakin is surly that he’s being put with the “babies” in order to catch up before he’s ready to move on. That 19 year old Anakin should know better, where 13 year old Anakin is given far more leeway, but ultimately Obi-Wan’s approach is the same–that he keeps being warm and understanding with Anakin, that even when he puts down boundaries, he still cheers him up and offers to talk whenever Anakin needs it, still understands that Anakin is a work in progress.

Just as they all are. That a Master is meant to be a student just as much as a Padawan. Obi-Wan is still learning and so of course he supports Anakin as he’s learning, whether it’s when he’s 13 or 19 or 23, he’s never expected Anakin to be perfect. Only to keep learning. And to talk to him whenever Anakin needs to, because Obi-Wan Kenobi doesn’t have to be vomiting his feelings everywhere to be warm and caring and open.

He talks about Qui-Gon. He talks about his own worries. He says the Jedi Council is wise, but they’re not perfect, he shows such faith and trust in Anakin, shows that his feelings are understandable, but he’s absolutely wanted. Obi-Wan tells him he’s doing well, that Anakin handles himself admirably. OBI-WAN KENOBI SUPPORTED HIM, TALKED WITH HIM, AND TAUGHT HIM. OBI-WAN KENOBI WAS SO GOOD WITH HIM AND THIS IS WHY THEIR LATER FALLING APART HURTS SO MUCH, BECAUSE THERE WAS SO MUCH GOOD AND CARE HERE.

That, at their very foundation, they are inherently an incredible, wonderful, warm combination for each other. Anakin and Obi-Wan, even at this young stage of their relationship, bring out so much good in each other, allow all these good things to flourish, and we get to see how good they were together. THANKS, STAR WARS, I’M CRYING ABOUT THE TEAM AGAIN.

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

More classic movies everyone’s seen but me!

They Live By Night (1948)

Bowie and Keechie are doomed young lovers in Nicholas Ray’s debut as a director. A lot of the tropes will be familiar to film noir fans -- you know Bowie and Keechie will never achieve the normal lives they want, and the movie’s ending feels as fixed and inevitable as Shakespearean tragedy, with avenues of escape closing off one by one. But a few elements set it apart. For one thing, there’s the Depression setting, which offers shabby cabins and dusty plains instead of L.A. clubs and streetscapes, and makes “economic anxiety” a real thing -- Bowie and Keechie’s wedding in particular is a tragicomic masterpiece, with the crooked justice of the peace subtracting elements based on the couple’s budget. The movies also draws power from the chemistry between Farley Granger and Cathy O’Donnell, which feels natural in a very stylized film, sometimes to the point of feeling intimate bordering on uncomfortable. (Howard Da Silva is terrific in a supporting role as the terrifying hood Chicamaw.)

Ray was given free rein as director, and They Live By Night has an experimental air that would prove highly influential, from the tricky opening helicopter shot to an inside-the-car sequence whose legacy you can see in Gun Crazy. Then there’s its rather odd unveiling: The movie was shelved for two years after it was shot, but circulated through private showings in Hollywood and became a favorite, with Granger tapped by Alfred Hitchcock for Rope and Humphrey Bogart offering Ray a lifeline as a director. They Live By Night isn’t a great entry point for film noir newbies, but will be interesting for fans of the genre.

Robert Altman remade this movie as Thieves Like Us, returning to the title of the novel that Ray adapted; that version is also on my list.

Under the Volcano (1984)

John Huston enjoyed tackling supposedly unfilmable projects late in life, following his adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood with this take on a 1947 novel by Malcolm Lowery. Albert Finney is wonderful as a drunken, self-destructive British diplomat, and there’s an undeniable pull to the movie -- I saw it a couple of weeks ago and can’t quite shake its suffocating mood of mild delirium. But it’s so, so bleak -- before you try it, make sure you’re up for two hours of unease and dread.

Silverado (1985)

I saw Silverado as a teenager, but came back to it recently because as a kid I’d barely seen any westerns and so had no idea what the movie was celebrating or looking to revisit. Seen through more experienced eyes, Silverado is most interesting because it isn’t revisionist at all -- with the exception of a couple of modern tweaks to racial attitudes, it could have been made in the same period as the movies writer/director Lawrence Kasdan is saluting.

Anyway, Kevin Kline and Linda Hunt are wonderful leads, as is Brian Dennehy as the sheriff who’s put his conscience aside, and virtually everybody you remember from mid-80s movies shows up at one point or another. It’s a lot of fun, at least until the movie runs out of steam in the second half and turns into a series of paint-by-numbers gunfights. The final running battle particularly annoyed me: Kasdan has had ample time to show us the layout of the town of Silverado, which would let us think alongside the heroes as they stalk and are stalked through its handful of streets, but his ending is random gags and shootouts, with no sense of place. Stuff just happens until we’re out of stuff.

Compare that with, say, Helm’s Deep in The Two Towers. Peter Jackson takes his time establishing everything from the geography of the fortress to the plan to defend it, and as a result we always know where we are during the battle and what each new development means for the heroes. That kind of planning might have made Silverado a modern classic instead of just a fun diversion.

My Brilliant Career (1979)

Judy Davis stars (opposite an impossibly young Sam Neill) as Sybylla Melvyn, a young Australian woman determined to resist not just her family’s efforts to marry her off but also the inclinations of her own heart. Sybylla is a wonderful character, a luminous, frizzy-haired bull in a china shop of convention, and she’s riveting in every scene. (Neill’s job is to look alternately hapless and patient, which he does well enough -- a fate that’s perfectly fair given the generations upon generations of actresses who have been stuck with the same role.) Extra points for Gillian Armstrong’s direction, which consistently delivers establishing shots you want to linger on without being too showy about them, and for sticking with an ending that, Sybylla-style, bucks movie expectations.

(This is an adaptation of Miles Franklin’s 1901 autobiographical novel, which I now want to read. Franklin also wrote a book called All That Swagger, which is such a great title that I’m happy just thinking about it.)

Red River (1948)

A friend recommended this movie -- the first collaboration between Howard Hawks and John Wayne -- after reading my take on Rio Bravo. And I’m glad he did: Wayne is terrific as Tom Dunson, a hard-driving rancher whose cattle drive to Missouri becomes an obsession that leads him into madness, and he’s evenly matched with Montgomery Clift, who’s his son in all but name.

Dunson begins as the movie’s hero and gradually morphs into its villain, with Wayne letting us see his doubts and regrets and also his inability to acknowledge them and so steer himself back to reality. Clift, making his debut as Matt Garth, is solid in a more conventional role (he looks eerily like Tom Cruise), and Walter Brennan happily chews scenery as Wayne’s sidekick and nagging conscience.

And there’s a lot of scenery to chew -- it’s wonderful to watch the herd in motion, particularly in a shot from over Brennan’s shoulder as the cattle cross a river -- and Hawks brings a palpable sense of dread to the nighttime scenes as things start to go wrong.

I would have liked Red River more if I hadn’t already seen Rio Bravo, though. Brennan plays the exact same role in that movie as he does here, Clift’s character is very similar to Ricky Nelson’s, and Hawks even nicked a melody from Red River to reuse 11 years later. (Hawks was a serial recycler -- he essentially remade Rio Bravo twice.)

A more fundamental problem is that Red River falls apart when Hawks jams Tess Millay into the story. We’re introduced to Tess, played by Joanne Dru, when Clift intervenes to save a wagon train besieged by Apaches, and her nattering at Clift during a gunfight is so annoying that I was hoping an arrow would find its mark and silence her. (She is hit by an arrow, but it only makes her talk more.)

Tess then falls for Clift, who seems mostly befuddled by her interest but blandly acquiesces. This is funny for a number of reasons: Beyond some really dopey staging, Clift’s love interest is pretty clearly a cowboy played by John Ireland and given the unlikely name of Cherry Valance. Their relationship is a bit of gay subtext that wouldn’t need much of a nudge to become text. Tess goes on to annoy Wayne in an endless scene that exists to forklift in a klutzy parallel with the movie’s beginning, and then shows up at the end to derail the climax in an eye-rolling fashion that leaves everyone involved looking mildly embarrassed. (Dru does the best she can; none of this is her fault.)

I was left wondering what on earth had happened, so I read up and discovered that -- a la Suspicion -- the ending was changed, destroying a logical and satisfying outcome penned by Borden Chase. Tess is a hand-wave to bring about that different ending, a bad idea executed so poorly that it wrecks the movie. Give me a few weeks and I’ll happily remember all the things Red River does right, from those soaring vistas to Wayne’s seething march through Abilene. But I’ll also remember how the last reel took an ax to everything that had been built with such care.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

I joined my new Zoom besties Amy Ratcliffe and Mike Chen to discuss our From a Certain Point of View: The Empire Strikes Back stories with Tim and Tom from Echo Base.

0 notes

Link

Talking with the awesome Tom Hoeler about my Wedge Antilles story in From a Certain Point of View: The Empire Strikes Back. This book was such a pleasure to be a part of!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Winter rolls along! No baseball! That means catching up with more classic movies everybody’s seen but me!

The Sugarland Express (1974)

This is Steven Spielberg’s first big-screen feature (1971′s Duel was made for TV), and it’s amazing to think it arrived just a year before Jaws, which would change American movies forever.

It’s impossible to watch The Sugarland Express without analyzing it in terms of Spielberg style, which is too bad, because it can be enjoyed perfectly well if you don’t know who the director is. Yes, there are some trademark long takes and inventive camerawork -- the most famous bit is a tricky 360-degree shot inside the getaway car that’s particularly impressive because it’s so easy not to notice -- but this is also a great character movie.

Goldie Hawn’s Lou Jean is simultaneously conniving and childlike, ruthless and clueless, and Hawn brings a frantic intensity to the part. Her husband Clovis is doomed the moment Lou Jean puts her half-assed plan in motion, and William Atherton (of Die Hard fame) does a superb job with an understated role, in which Clovis’s real tragedy is how timidly he navigates the constrained possibilities of his life. They’re joined by Michael Sacks as a kidnapped state trooper, and the three make for a compelling ensemble -- people who understand each other and grasp that their circumstances could easily have been switched around by a chance here or there.

The movie’s ambitious and thoroughly modern -- it’s a chase movie and a marital comedy and a slice of social commentary, and it switches lanes with skill and self-confidence. Maybe it doesn’t quite stick the landing -- there’s a little too much movie blood and the sun-soaked last shot feels like a stylistic departure -- but the ending is gripping even though it unfolds the only way it could, and that’s a hard trick to pull off.

Extra credit because even a relatively uninformed movie fan like me will have a blast moving both forward and backward from The Sugarland Express -- it wouldn’t exist without Bonnie & Clyde, but Raising Arizona wouldn’t exist without it, to identify just two beads on an intriguing string.

Rio Bravo (1959)

Westerns are my comfort food -- give me the right proportions of dusty streets and swinging doors and cacti against sunsets and I’ll overlook a fair number of cinematic/narrative sins. And Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo whips up the classic ingredients with the nonchalant skill of a veteran short-order cook in a beloved diner -- a tumbleweed even rolls into one of the leads in the first reel, as if to say, “What? It’s a western!”

Rio Bravo is usually framed as a rebuke to High Noon and 3:10 to Yuma, which Hawks and John Wayne despised because those movies dared to depart from the western tropes of flinty-eyed, self-reliant sheriffs and frontier folk banding together. The film Hawks and Wayne made in response is rock-ribbed in its values, unfolds at a languorous pace, and is often mawkish. (It also jerks to a halt for back-to-back duets with Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson, while Wayne stands there and smiles.) It shouldn’t work -- and, to be clear, I don’t think it’s nearly as interesting as the movies it’s arguing with -- but it does.

For one thing, there’s immense skill brought to the storytelling and filmmaking. There’s a self-confidence behind that languor that draws you in, and while the characters are hoary stock figures, their interactions rarely if ever ring false. The actors are solid, too: Martin is a lot better than you might guess as Dude, the deputy with an alcohol problem; Nelson holds his own as a young gunslinger who doesn’t want to get involved but of course eventually does; Walter Brennan has a grand time bouncing off Martin and Wayne in their shared scenes; Angie Dickinson brings some shade and nuance to the role of a gambler’s widow trying to extricate herself from a checkered past; and the bit players are all threatening, comedic, hapless and helpful in the proportions you expect and want.

But unsurprisingly, Wayne is the secret weapon -- the story treatment for Rio Bravo didn’t bother giving his character a name, just calling him “John Wayne.” Imitations of Wayne focus on the swagger and the tough-guy talk but miss that his performances turn on the moments when his characters’ weaknesses undermine their strengths. Wayne’s Sheriff John T. Chance is gentle with Dude’s struggles, knowing well-chosen nudges are the best way to keep his troubled deputy on the right path, and he’s utterly at sea navigating his feelings for Feathers, Dickinson’s character. The Wayne-Dickinson pairing is yet another of those May-December romances that movies of the era were always foisting on actresses, but Wayne wisely leans into the problem, letting Chance be tongue-tied and awkward as the more confident Feathers steers him through uncharted emotional terrain.

Wayne became more cranky and reactionary as he aged, but he never lost the insight that strength is only interesting if paired with weakness. That dynamic sells Chance and Rio Bravo wonderfully. And hey, the Martin-Nelson duets are actually pretty good.

Hawks and Wayne would essentially remake Rio Bravo two more times, first as El Dorado and then as Rio Lobo, and while I’ll tell you now that I don’t feel the need to see either one, jump ahead a couple of years to a late night where I think, “a western would be fun right now,” and I’ll probably wind up watching one of them. Because I bet they’ll work.

That Thing You Do! (1996)

The story of a one-hit wonder band, written and directed by Tom Hanks. The cast is terrific, particularly the luminous Liv Tyler; the title song (written by Adam Schlesinger of Fountains of Wayne) is not only good but also pitch-perfect for its era; and the giddy whoosh of the Wonders’ sudden rise to fame carries the movie along effortlessly for quite a while.

There are only two problems -- but unfortunately, they’re pretty big ones.

First of all, the movie jumps the track completely in its last 20 minutes or so. Tyler’s big speech to her self-obsessed boyfriend feels completely out of character; Tom Everett Scott’s drummer hangs around the most accommodating studio in music history and has a miraculous chance meeting with the jazz musician he idolizes; the hotel’s magical concierge uses the same gag twice and then breaks the fourth wall ... and all of this happens in such rapid succession that I thought I’d hit my head. The movie’s humming along pleasantly enough and then WHAM! everything stops making sense and it never regains its footing.

Second, after a couple of hours it’s already fading from memory, leaving behind the title song, the fun of life on the road and Tyler. I think that’s because while That Thing You Do! is invariably pleasant, it’s also utterly bloodless.

Nothing is played for any stakes. Giovanni Ribsi breaks his arm and loses his spot in the band to Scott, but never seems bothered that he missed out on his friends’ rocket ride. The Wonders’ first manager excuses himself with nary a peep once Hanks arrives to take over. The veteran bands on tour with the Wonders brush the newcomers off at first, but pretty soon they’re all friends. The Wonders’ bassist is infatuated with a Black singer, which would have raised eyebrows in 1964, but the relationship barely makes a ripple. Despite ample warnings that it’s coming, the conflict in the band is mild at worst. Even the love triangle involving Tyler is resolved simply and with no particular fuss -- the Wonders’ lead singer breaks up with her, the drummer takes up with her, and all is well.

The movie presents an attractive surface -- despite all of the above, when I heard there was an extended cut I thought, “I’d hang around with these characters for 40 more minutes” -- but there’s absolutely nothing underneath it. Given the talent on both sides of the camera and the obvious care with which it was made, that’s a shame.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

More classic movies everybody’s seen but me!

Night of the Hunter (1955)

Just an amazingly strange film. It’s an American gothic, directed by Charles Laughton, of all people. How a veteran English actor wound up creating a singularly original piece of primal American outsider art is a fascinating puzzle, but he sure did. I watched Night of the Hunter in bemusement, not quite sure what I was watching, but know parts of it will stay with me forever. There’s Robert Mitchum’s shadow falling on a window, the mesmerizing shot of a dead woman underwater, the slow boat trip through dreamlike vistas, and the spiritual that becomes a duet between Mitchum’s killer and Lillian Gish’s devout protector. And more that I’m sure will bubble up over time.

In a Lonely Place (1950)

A taut film noir starting Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame, whom you’ll probably remember as Violet, the bad girl from It’s a Wonderful Life. Bogart is terrific, channeling the manic, slightly dangerous intensity he brought to some of his earliest roles and never becoming a caricature, and Grahame is every bit his equal. Extra credit because Grahame was married to director Nicholas Ray, and the knowledge that their marriage was failing as the movie took shape adds an uneasy frisson to the plot. (Grahame’s life would make a movie that’s almost too crazy to be believed, but that’s another story.)

Cimarron (1931)

A pre-Code Western about the settling of Oklahoma, Cimarron is derided now as a period piece not worthy of the honors it garnered, but while I didn’t find it particularly compelling, so harsh a judgment seems unfair. The story has sweep and ambition that holds up, uses a wonderful visual cue of opening each act with a view of the Oklahoma town and how it’s changing, and it was probably a lot more progressive in its day than it’s given credit for. There’s a wonderful bit where Yancey Cravat (played by Richard Dix) is in a shootout with an outlaw, and the sandbag next to him springs a hole and leaks sand after a bullet hits it. Standard-issue movie magic now, perhaps, but I bet it was innovative at the time, and it’s a bit that still works perfectly.

The Great Train Robbery (1978)

One of two Sean Connery movies I watched after hearing of his death. This one’s a big, brassy heist movie, but the performances elevate it above that perfectly serviceable level. Donald Sutherland merrily chews the scenery as Connery’s partner in crime, and there’s a thrilling bit where an impression has to be made of a key in terrifyingly short order.

The Man Who Would Be King (1975)

Connery is solid in this adaptation of the Rudyard Kipling story, directed by John Huston, though Michael Caine walks away with the picture as his sidekick. Interestingly, Huston had been trying to make the movie for years, and originally wanted Clark Cable and Humphrey Bogart in the parts that went to Connery and Caine. There isn’t an enormous amount that will stick with you, perhaps, but you’ll be entertained for two hours, and sometimes that’s more than enough.

Blithe Spirit (1945)

Maybe I was just tired, but this one didn’t do much for me. David Lean’s considerable gifts aren’t put to much use, and the characters keep behaving in ways that are convenient for setting up gags but don’t have much resemblance to things actual people would do. Still, there is some sharp/fizzy dialogue, as you’d expect from something based on a Noël Coward play.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Our A Met for All Seasons series at Faith and Fear in Flushing continues with a chronicle of my quest for a decent color photo of momentary Met Al Schmelz. (Hint: This isn’t it.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m halfway through The Clone Wars: Stories of Light and Dark and it’s about what I expected, it’s mostly just straightforward retellings of the episodes. I had hoped for a bit more thoughts being woven into the perspectives, though I wouldn’t say any one of the stories I’ve read yet is worthless, either. It’s perfectly serviceable so far, is generally my feeling. (Mild, mostly general feelings spoilers so far, but feel free to block the “#solad spoilers” tag if you want to remain completely unspoiled!)

General thoughts on the stories I’ve read:

“Sharing the Same Face” (Yoda) by Jason Fry

- I’ve always enjoyed Fry’s writing and he really does a great job with Yoda’s point of view and the mix of whimsy and ancient wisdom that he contains in this mysterious mix. The moments Fry describes in the story, especially Yoda first touching down on Rigosa, the way he’s constantly feeling the clones’ emotions, the sense of wonder at the life around him, the way he sits down mid-battle to meditate left me feeling wonder at that anew, really are exactly what an anthology like this should be. I’d have read the book just for this story alone.

“Dooku Captured” (Dooku) by Lou Anders

- I like Anders’ writing as well and this was a very solid Dooku pov. A lot more could have been done with it, I feel like it was a missed opportunity to examine Dooku’s feelings on his lineage (there is one line that mentions Qui-Gon that got me in the feelings place, though!) or a chance to really go full-throttle with the hilarity like he did with Pirate’s Price, but it was more middle of the road and a fairly straightforward retelling. I think it would have been served better picking a lane (hilarious or feels-laden) instead of half-and-half between the two, but I did take notes for caps that I wanted to yell about, so clearly I enjoyed it.

“Hostage Crisis” (Anakin) by Preeti Chhibber

- I think my own expectations of Anakin’s complexities of character got in the way of this story, because it has some cute Anidala moments, but other than that it’s a very straightforward retelling of the episode that really doesn’t examine Anakin’s character at all or the bigger themes in SW, which felt like a huge missed opportunity for me. But, again, those were my expectations going on and the tone of the story wasn’t what I expected, so that’s not really fair. Worth reading if you want some cute, light-hearted Anidala moments.

“Pursuit of Peace" (Padme) by Anne Ursu

- I have mixed feelings about this one, I feel like it’s a mix of my own expectations getting in the way again, that there are moments that I really enjoyed about Padme’s view of the Republic falling into economic ruin, that she’s really kind of unsympathetic to Mina’s point of view, and of course all the discourse surrounding Padme’s speed about how buying people is making the Republic poor. Other than the way she thinks about the bounty hunters (giving snide nicknames to them didn’t really feel like Padme to me, but that might be a personal thing), I feel it was pretty faithful to what would have been going through Padme’s head in the episodes. It’s just that that’s kind of complicated re: whether that makes for a good Padme story.

“The Shadow of Umbara” (Rex) by Yoon Ha Lee

- Sadly, this one was actually the most disappointing to me, because it’s such an intense arc in the show and it’s not that Rex’s character doesn’t have weight here, but that there’s really nothing added to what we already get on the screen. It’s a perfectly fine retelling of the story in text form, but with such an important arc to the story, I wish there’d been something more to this version of it. There’s nothing wrong at all with the story itself! It’s in what I can’t help wishing it had been instead.

“Bane’s Story” (Cad Bane) by Tom Angleberger

- Angleberger does great with upbeat, fun narrative styles (Chewbacca and the Forest of Fear! is a hilarious book for that) and I very much enjoyed his take on Cad Bane. It doesn’t add anything to the episode, you don’t really get a sense of who Cad Bane is that you didn’t already know, but it’s an enjoyable ride along the way, just a fun story to read.

“The Lost Nightsister” (Ventress) by Zoraida Córdova

- This is the strongest story of the book so far, imo! I’m only halfway through it, but this is what I wish the whole book had been like–there’s a lot of moments that really dig into Asajj’s character and what place she’s in mentally/emotionally after the genocide of her people by Dooku and Grievous. The sense of aimlessness, the scattered and hurt feelings, the lack of focus, the loss of her sisters, it’s all woven in really well. I’m only halfway through the story but it’s packing exactly the punch I’d hope for from it.

151 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New book out today! The Clone Wars: Stories of Light and Dark adapts TCW episodes with a wonderful roster of authors, including some folks who are new to the GFFA. (Welcome, shinies!)

My story, “Sharing the Same Face,” retells the episode “Ambush” from Yoda’s point of view, and checks something off my bucket list -- despite writing a lot of books and stories, I’d never had a chance to write Yoda beyond a cameo or two.

Hope you’ll check out the book and enjoy it!

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via This One Has a Chance)

Our A Met for All Seasons series continues at Faith and Fear in Flushing with Mike Piazza, 2001 and a home run for the ages.

0 notes

Video

youtube

(via The Shot Heard Through the Spring)

Before the Mets play baseball again on Friday, a look back at the last moment of 2019. Thank you, Dom Smith -- thank you more than any of us could have known.

0 notes

Photo

Faith and Fear in Flushing’s A Met for All Seasons series continues with an appreciation of Todd Pratt, a backup catcher whose moment in the sun was a long time coming -- and joyous indeed.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

With baseball quickly approaching (for who knows how long), time for a pandemic installment of Classic Movies Everyone’s Seen But Me!

Summertime (1955)

David Lean works small (for him) in terms of both running time and vistas. He does a wonderful job with Venice, making the city practically a character in its own right -- and as someone who knows Venice well and loves it, I only caught Lean cheating on the geography a couple of times.

The real star isn’t the setting but Katherine Hepburn. Hepburn plays Jane Hudson, a middle-aged secretary from Akron, Ohio, who claims to have given up on romance. She hasn’t, of course, but it appears as if romance has given up on her -- Jane is a third wheel for the movie’s other couples and feels left out of even men on the make’s appraisals, spending the early part of the movie bonding with a street kid and the widow who runs her pensione. I’d write that it’s the kind of part that wasn’t written for actresses in the 1950s, but it’s the kind of part that isn’t written for actresses today. Hepburn inhabits the character beautifully, letting you see Jane’s hesitation and heartbreak in piercing scenes that sometimes rely entirely on body language, and Lean gives her the space to work, even when it’s an uncomfortable experience. A near-flawless performance.

The love story feels a little slight at first, but the ambiguity about what you should feel is intriguing. (Apparently this was even more the case in The Time of the Cuckoo, the play upon which Summertime was based.) Extra points for the Code-evading shot that tells us two characters have consummated their relationship. It’s only slightly subtler than the famous conclusion of North by Northwest.

Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941)

Claude Rains has a marvelous time as the title character, an unruffled bureaucrat in charge of the afterlife who has to fix the case of a boxer taken up to Heaven a bit too soon. (The film was remade in the 70s with Warren Beatty and called Heaven Can Wait, the name used in its first incarnation as a play.) Rains is terrific, but the rest of the movie is pretty forgettable: Robert Montgomery is genial but not particularly memorable as prizefighter Joe Pendleton, and the plot logic breaks down completely in the endgame.

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Another Rains vehicle, in he stars as the evil Prince John, scheming brother of Richard the Lionhearted and foe of Robin Hood, played (of course) by Errol Flynn. Rains somehow retains his dignity despite a horrific wig and some astonishing costumes -- there’s one black and silver getup whose shoes have to be seen to be believed.

But all the characters are wearing ridiculous things all the time, shown off via the movie’s thoroughly saturated palette. There are men-at-arms in purple and pink motley, the merry men’s green tights, Flynn’s honest-to-goodness bedazzled emerald top, a lady-in-waiting’s Fancy Shriner fez, and we haven’t even discussed the get-ups Olivia de Havilland sports. The costume designer whizzes past All Too Much before the first reel’s over and just keeps going. And the dialogue keeps up with the costumes. Robin Hood may be the campiest movie I’ve ever seen -- it makes The Birdcage look like Shoah.

Flynn is capable with a sword and performs his stunts with swashes properly buckling, but man oh man could he not act. He has two basic expressions: fighting and making merry, and looks a little lost when the story requires him to investigate whether a situation requires choosing between the two.

Fortunately that doesn’t happen too often, and you’ll have fun anyway. This is the template for about a billion adventure stories made since then, and it’s entertaining even when you’re not elbowing the other person on the couch to point out what was waiting in Claude Rains’s dressing room this time. Think of it as a live-action cartoon and enjoy the ride.

Love in the Afternoon (1957)

Audrey Hepburn is the innocent, cello-playing daughter of a Paris private investigator (Maurice Chevalier) who interferes with her father’s work by preventing an American playboy (Gary Cooper) from getting shot by a jealous husband, then pretends to outdo the playboy at his own no-consequences game.

The story is light and amusing, with Chevalier ably serving as the fulcrum who helps it turn into something poignant and more interesting at the end. (The voiceover as coda, by the way, was added for Code reasons.) And Billy Wilder (co-writing and directing) guides the ship with a light, skilled hand -- the scenes between Cooper’s Frank Flanagan and his hired band are particularly fun.

There’s a fatal flaw, though: While Hepburn has never been more luminous, Cooper is too old to be the leading man. Wilder knew this, using soft focus and dim lighting in an effort to be kind that just calls attention to the movie’s fatal flaw. Moreover, Flanagan’s neither particularly interesting nor pleasant, so you never believe Hepburn’s Ariane would actually be interested in him. (He’s rich, granted, but she doesn’t seem to care about that.)

Directors kept doing this to Audrey Hepburn in the 1950s: Three years earlier, Wilder stuck her with a half-rotted Humphrey Bogart in Sabrina; in 1957 she also had to put up with a mummified Fred Astaire in Funny Face. Beyond the fact that it’s creepy, it doesn’t work for those stories.

I’m going to look on the bright side: Hepburn deserves even more adulation than she gets, since she rises above her AARP romantic leads to carry all three pictures.

The 39 Steps (1935)

A clever early Hitchcock I found intriguing because you can see the visible language of film evolving before your eyes. Some scenes look utterly modern, with intriguing camera angles and blocking, but they’re right next to oddly static compositions, or scenes filled with cuts that cross the line for no apparent reason. But there’s also a justifiably famous transition shot from a cleaning woman’s horrified discovery to a train whistle, a tricky perspective change from inside a car, and some other nice surprises.

The movie is a prototype Hitchcock thriller, with a plot that carries you along provided you don’t ask too many questions. (Or any questions, really.) But the movie hits its stride surprisingly late, coming into focus once Robert Donat’s Richard Hannay winds up manacled to Madeleine Carroll’s Pamela. Hang around that long and you’ll be well entertained.

McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

This one made my list because it was an inspiration for Solo, a Star Wars spinoff movie I think deserved a better reception and suspect will be viewed more fondly in time. Yep, that’s Warren Beatty’s fur coat that Alden Ehrenreich wears, and the bar Beatty visits in the town of Presbyterian Church is a dead ringer for the one where Han and Lando Calrissian meet over cards.

So that was fun. As for the rest, after my usual post-movie reading, I get what Robert Altman was going for. This is an anti-Western that relentlessly inverts the genre’s tropes, with the climactic gunfight happening not in the center of town before all eyes, but scarcely noticed as the townspeople rush to put out a fire.

But I found that more interesting to read about than to watch. I was never invested in Beatty’s McCabe or Julie Christie’s Mrs. Miller, finding them less memorable than a young visitor who runs afoul of trouble (Keith Carradine) or the lead bounty hunter sent after McCabe (Hugh Millais, exuding genial menace).

Still, the movie has a powerful sense of place, I keep finding myself thinking about it, and lots of people whose opinions I respect consider it a classic. So perhaps I’ll revisit this one someday. But for now, my conclusion is that I’m missing whatever gene you need to appreciate chilly, airless Hollywood art-house movies of the 1970s -- a movement, ironically, that screeched to a halt when Jaws and Star Wars introduced the era of the summer blockbuster.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Our A Met for All Seasons series continues at Faith and Fear in Flushing with 1996, Rey Ordonez, and hearing that sound. Oh, and we’ll discuss this amazing play.

0 notes

Link

Faith and Fear in Flushing’s next Met for All Seasons is Wilmer Flores, who was front and center for one of my most enduring and affecting Mets memories.

0 notes