Note

hello! speaking of eugène, do you know if sisi ever kept in touch with or referenced her beauharnais cousins, like the bernadottes or leuchtenbergs? do we know what she thought of them (if she did at all)?

Hello! This is something that I've also been wondering for a while. They did met sometimes with the Bernadottes, but I don't know if they treated each other as cousins. In Valerie's diary I found two mentions of them, first in 1885 in a letter of Franz Josef to Valerie about a visit of King Oscar II of Sweden (Josephine of Leuchtenberg's son and therefore Elisabeth and FJ's first cousin once removed). However I have no idea what the letter said because Richard Sexau, the guy that transcribed the diary in which the published edition is based off, decided to not transcribe it. The second mention is from 1886, when Valerie and Elisabeth were in Baden and met the Crown Prince Gustaf of Sweden (future Gustaf V, and grandson of Josephine of Leuchteberg) and his wife Crown Princess Victoria. The Crown Prince and Princess hanged out with them, Duchess Mathilde (Sisi's sister), and her daughter Maria Theresa "Mädi", whom apparently was close friends with Victoria (Valerie calls her "Mädi's beloved Viki" and also notes that she's very likeable). This is all I could find, but there probably is more.

I don't know about Elisabeth, but Archduke Max did kept contact with Empress Amelie of Brazil (Auguste and Eugène's daughter) even after Princess Maria Amelia (his fianceé) died. He visited her often, and I'm pretty sure they mentioned in each other's wills. Also I read in a biography of him that when he was Viceroy of Lombardy-Venice he tried to imitate Eugène, but I'm not sure how accurate this is.

About the rest of the Leuchtenbergs: Auguste, 2nd Duke of Leuchtenberg married Maria II of Portugal in 1834 but died shortly after without issue. His brother Maximilian, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg married Emperor Nicholas I's daughter Grand Duchess Maria Nikolayevna and moved to Russia, and for what I gathered eventually this branch loss all its connections to Bavaria. Eugénie (who was present at Sisi's birth and was one of her namesakes) married a prince of Hohenzollern; they visited Munich many times so maybe she met Sisi when she was more grown up, but she died in 1847 and had no children. And lastly Theodolinde, the youngest surviving daughter, married the future Wilhelm, 1st Duke of Urach, had four daughters and died in 1857. I know nothing more about this branch, but fun fact: Duke Wilhelm remarried and had a son, who later married Duchess Amelie in Bavaria, a niece of Empress Elisabeth.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Josef Albert

Maria Josepha of Portugal, Duchess of Bavaria

circa 1874

457 notes

·

View notes

Photo

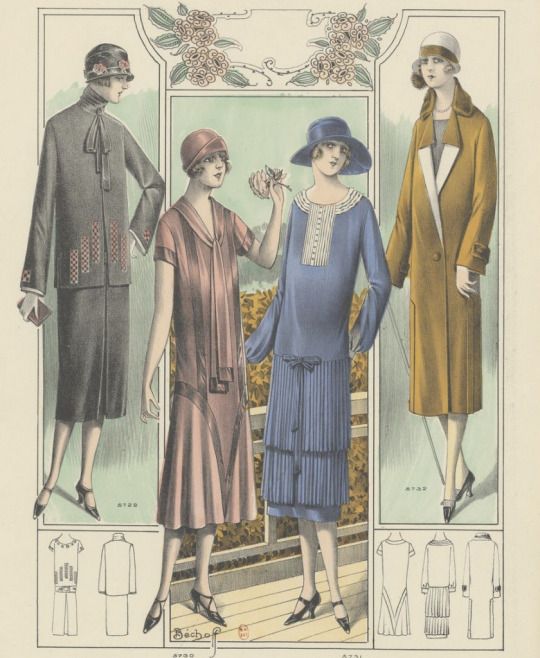

La Mode nationale, no. 32, 11 août 1894, Paris. No. 1. Toilette d'intérieur. Bibliothèque nationale de France

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archduchess Mathilde of Austria-Teschen, by Unknown artist (left). Although it was auctioned in March 2022 as a portrait of Archduchess Margarethe Sophie, the painting is clearly based after this photography of Mathilde (right).

Via Neumeister

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Albert Gustaf Aristides Edelfelt (Finland-Swedish, 1854-1905)

Young Woman In Black, 19th-20th century

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Early Victorian Antique Portrait, 1850

Oval portrait of a serene woman with upswept hair. Could be a mourning piece as there isn’t anything going on below the neckline. [x]

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Follow Victorians, Vile Victorians in Patreon for more original fiction like this for free.

"But you can't wear the red scarf, ma'am!" But the black scarf, Sarah admits, is still in to soak, having become unbearably frowsty, and the white one, despite Sarah's best attempts, is streaked with dull yellow stains. Why anyone thought of wearing white silk next to their neck is a mystery to her. "You could wear a shawl?" Sarah suggests tentatively, but her mistress doesn't reply. She detests shawls, they remind her of market women.

Sarah is not elevated to the status of a lady's maid, and washing the black scarf had taken its place alongside tasks like cleaning out the fires. Mrs Ampleforth had noted, even as a child, that while her mother professed to be exhausted after a tea party, Sarah and her workmates were banging about the kitchen before it was light, and could be heard still clearing up long after she had gone to bed. It had left her slightly in awe of servants, and the feeling had never quite worn off.

Anyway, she explained to her employee, though the sun is bright there is a chill gusty wind, it is still only February, Pedro needs his walk, and who is she going to meet on the Common at this time in the morning? She opens the front door, then steps smartly back inside. Fumbling under her coat, she releases the strings of her crinoline, steps out of it, and hangs it over the newel post at the foot of the stairs. "Madam!" says Sarah in horror. "You'd best pop that straight upstairs, in case anyone calls" she replies calmly, and steps out into the tail end of the storm, her skirts clutched firmly in her hand.

If she hadn't got out of the house, she says to herself, she would have screamed and, having screamed, started smashing the china. The sandy paths, though still damp, hold no puddles, and progress is far easier (and her legs warmer) without the crinoline swaying and bucking in the wind. The scarf cracks and flaps like a flag, pulling out every time she tucks it in, and she ends up clutching it in her other hand. It's a good job there are no gates to open, she thinks, as she doesn't have a hand free. The broad brimmed hat wasn't the best idea, but it is so firmly pinned to her tight plaits that its efforts to escape are futile.

She was wrong, however, about meeting no-one. She passes several working men, and an old lady collecting firewood blown down overnight, who count, for social purposes as No-one, but then she realises the figure chasing his round hat into a clump of juniper is the vicar. In Westheath, the church is out at the end of a lane, and this must be his short cut to the village.

"A red scarf, Mrs Ampleforth?" he says, instead of the customary how-d'ye-do. As he has started the conversation without the usual grace notes, she will follow suit. "Red is God's colour too, Vicar. I am not aware of the Bible discriminating amongst shades." This is clearly more than he bargained for, and he bows and walks on without anything more. She resists the urge to turn her head and see if he is looking back at her.

Nonetheless, the sermon the next Sunday, taking as its text "Render unto Caesar", seems rather pointed to Mrs Ampleforth, seated in the third row in her clean black scarf. Several working men and an old lady collecting firewood have been quite sufficient to pass the news round the village that Mrs Ampleforth had been seen wearing scarlet, while still in second mourning, although fortunately the collective lack of sartorial acuity had barely noticed that her gown had seemed rather bedraggled, and not identified the actual lack of crinoline.

The vicar expands, at length, on the topic of fitting in with our fellows, conforming with what is expected of us, and generally not outraging public decency. As Mrs Ampleforth is close to the front, everyone else has the luxury of staring at the back of her head, while she has only elderly Major Binks to hide behind, and he is asleep as usual. She holds her gaze with rigid stoicism on the altar cross and refuses to blink.

The rest of the service passes in its normal dreariness, and if the vicar, standing to greet his parishioners in the porch before they step out into the rain awaits Mrs Ampleforth with chagrin, he gives no sign of it. Perhaps he is ready with forgiving compassion for her to step forward, eyes downcast. Not a bit of it. "An interesting sermon, Vicar" she observes sharply "one wonders what Our Lord would make of the suggestion that we should take worldly opinion as our moral guide?" She has had half an hour to sharpen and perfect her barb, and is pleased with her firm delivery.

If the vicar has flinched, if she has hit home, she does not see, for she has stepped out into the drizzle with her nose in the air and her gaze straight ahead. On Monday morning, however, when she walks down to the post office with Pedro at her side, she is wearing the scarlet silk scarf like a flag of war.

Reactions are so varied that she is soon too amused to feel any awkwardness. The better sort of villagers simply pretend they have not seen her. Those below her in the social scale blush, or try to hide a sly smile. The children, of course, are unaware of the depths of her outrage, although some of the older ones gasp open mouthed, vaguely conscious they are witnessing a phenomenon. Does she really hear a low buzz of voices as she ducks to go through the low door of the post office, or is she imagining it?

In the darkened room there is only the postmaster, yet even he leans forward and speaks in low, conspiratorial tones. "Aren't you concerned about what Mr Ampleforth might say, looking down?" His tone is amused, the way he raises his eyes to heaven theatrical rather than pious. "Scarlet was his favourite colour, and it was he who gave me the scarf." she says tight-lipped. It is her prepared speech, but the post-master breaks into a broad grin. "Good for you, ma'am", and she finds herself smiling shyly in return.

The postmaster is a notorious free-thinker, and rumoured socialist: but he is also the village's news-service, and she knows that the fact that the disgraceful scarlet-wearing is a tribute to her tenderness for the late Mr Ampleforth rather than an insult to his memory will be disseminated very quickly. But as she and Pedro make their way back, she is restless and fidgety. She may wear a scarlet scarf every day for a month, but it hardly signifies anything other that a desire to tweak the vicar's nose.

Other women, she vaguely appreciates, experience a dissatisfaction with the ways things are arranged. Not such quibbling and, she trusts now purely temporary, inconveniences such as those affecting property, or education, or the vote: these, she is confident, will sooner or later be swept away by Progress, in this modern age. The Sarahs of this world, she is embarrassingly aware, have good reason to be as dissatisfied with the Mrs Ampleforths as with the law. Does the postmaster's rumoured socialism free the Sarahs from tyranny, or only their fathers and husbands, she wonders. She must ask him next week.

Her sister-in-law Jessica has Turned To Rome, which she feels must only make things worse, not better. As if having a husband wasn't bad enough! she catches herself thinking, which is strange, because she never thought it while Henry was alive.... Her mother recommends Good Works, and her brother says she should marry again, and is rather offended at the response he gets. "You need children" he goes on, undefeated. "No I don't!" she snaps, surprising herself.

Turning to the catalogues of progressive publishers, she embarks on a course of reading, but each new book sways her one way until the next comes along to sway her another. The solution to poverty isn't penwipers, and there is more wrong with women than Rational Dress can solve (though it is very tempting): the postmaster, tentatively consulted, concurs and supplies her with a bundle of pamphlets. She agrees with everything they propose, but finds their suggested methods of achieving it naive in the extreme.

Westheath may be charmingly rural, but the train from the little station beyond the windmill whisks her into the centre of London within half an hour. Sensibly shod and soberly dressed, red scarf apart, she tries every institution and library. She attends lectures with titles like "What is religion?" or "An Examination Of The Proposed Methods For Reforming The Plebiscite" and finds, regardless of the advertisement, regardless of the serious, nodding heads in the auditorium, that the point has been sorely missed somewhere along the way.

The old vicar, his grey hairs no doubt dragged down in sorrow, if not to the grave at least to Bournemouth, retires, and his place is taken by a wiry, nervous man who has earned Westheath by service in the East End. She attends church, which she had not quite given up doing, to hear what he has to say. His first sermon explores an obscure point of theology in Saint Augustine. After the service, at the church porch, she shakes hands. "Did you preach like that in the East End?" she asks with wide-eyed innocence. "Good Lord, no. It was all very Evangelical. Why, do you think it went over their heads?" She cannot resist a smile. "Well, it certainly went over mine!" and leaves him there, blushing slightly.

She is of course, by now, no longer young, and the beauty that turned Mr Ampleforth's head is not there to cause awkwardness between her and the Reverend Hughes. Nevertheless, villages being villages, their conversations are conducted at the church porch, or in front of the post office, and are brief. "You should try the Greeks" he ventures one week, having divined from the ether a need. "Which ones?" she asks, thinking vaguely of heavily-bearded church fathers. "I'll make you a list." he promises, boldly. If Mrs Ampleforth has put on weight, and grown grey: if her teeth are no longer so numerous as they were, she is still an imposing woman. "I don't read Greek..." she adds cautiously. "I never for a moment supposed you did." And they laugh nervously at his temerity.

She orders the books on the list from a publisher specialising in cheap editions for the working man. They are refreshingly small, after some of the books she has waded through. They are also surprisingly hard. If people were at this stage more than two thousand years ago, even before Christianity, how is it the world is still such a muddle? "You must try Marcus Aurelius next" says the Reverend Hughes. "I found him a great solace during my worst times." Somewhat alarmed at this encomium, she orders him too.

Somewhat later, she orders a deluxe edition, bound in green morocco with gold tooling. The Reverend Hughes has moved on to Anglo Saxon poetry, and though she is warmly appreciative of the copy of The Wanderer, beautifully calligraphied in his own handwriting, which falls from her Christmas card, she tells him she is more the Ancient Roman than the Dane. The difference of taste does not sour their friendship.

As the years pass, Mrs Ampleforth gets heavier, and greyer, and more of her teeth fall prey to the dentist, while the Reverend Hughes gets leaner, and wirier, (a difference which may be due to her distinct fondness for cake, and his for long solitary walks) and continues to deliver his baffling sermons. The Reverend Hughes flirts briefly with Kierkegaard, but Mrs Ampleforth, despite her other reading, remains faithful to Marcus Aurelius.

As she had predicted during an argument with her sister, all those injustices of property, and education, and politics which had exercised them so wither progressively with the passing of the years, leaving her nieces and, in time, great-nieces aware only of others, as yet unresolved. People forget there was ever a Mr Ampleforth, regarding her title as an honorific, like that bestowed on cooks. She gains, and keeps into extreme old age, a reputation for not suffering fools gladly, and being a good place to turn in a crisis. She watches her contemporaries decline into complacency or fretfulness - all except the Reverend Hughes, who expires in the fullness of years while wrestling with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

Mrs Ampleforth lives on, missing him less than she had expected. The older she gets, the fuller her days seem to be. Her maid, Sarah's grand-daughter ("Don't think of it as 'service' " says Granny, "think of it as quite a cushy job with a nice boss. You don't have to stay forever, just till she finds someone else." Which was twenty years ago...) reads the newspaper to her every evening, as the print has got so small these days, a task which is especially bonding during the Great War, when Mrs Ampleforth loses a favourite great-nephew and Sarah's granddaughter loses her sweetheart. She sinks slowly and gently, much comforted by Marcus Aurelius, and eventually passes during the General Strike, her main feeling one of irritation at not knowing how it will end.

She encounters the Reverend Hughes again almost immediately. He is wearing a goatskin, and his wiry limbs are very sunbrowned. She, for her part, seems to be dressed in something soft and loose and pale - bliss after a lifetime of corsets - and her arms, when she glances down at them, are bare and unwrinkled. Looking further, she sees, peeking out from under the creamy wool, feet that have never been forced into tight patent leather boots. Her own dress is expected enough, but his is a puzzle.

"Is this heaven?" she asks tentatively, gazing into a crystalline distance resembling, quite remarkably, that in John Martin's painting at the Tate. "I rather think" says the Reverend Hughes, leaning picturesquely on a staff of rough wood "it must be the Elysian Fields". But just as she no longer cares what happened in the general strike, she meets this observation with quiet calm. "And is everybody here? Or is there ... another place?" The Reverend Hughes observes that this is rather unlikely, as he has met a number of people who would undoubtedly be in it, if there were.

"Really? Anyone interesting?" asks Mrs Ampleforth with excitement, thinking of Ivan the Terrible or Caligula. "Not really..." says the vicar, brushing away an affectionate butterfly "only my Latin tutor and the like. I haven't yet encountered anyone I didn't already know." As she ponders this intriguing peculiarity, a speck in the distant meadow resolves itself into the shape of a bounding, hairy animal with a long pink tongue. "It's Pedro!" she cries, pressing her hands together. "Oh, how awfully, awfully glorious!" Behind the dog labours a figure in an embarrassingly short tunic, carrying a basket. It is the postmaster.

"I say, Emily!" he hails, approaching. Who? My goodness, that will take some getting used to! She hasn't been Emily to anyone since her sister-in-law died. Which is a thought: she wonders what Jessica Ampleforth makes of the present arrangement? The postmaster is breathing a little hard from climbing the hill. "I say!" he repeats "What ho, Fred? Would either of you like a fig? They're awfully good this year Emily. Did you get the vote yet?" The figs are large, a lustrous purple, and wonderfully sweet. "Oh yes, ages ago. Straight after the War." He looks blank. "Which one?" She takes another fig and says "Never mind, eh?" Pedro runs round them in circles, chasing the butterflies.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Victorian Mourning Dress, c. 1880, black silk and netting, lent by Evan Michelson. Photo by Irving Solero.

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Widow with a child at her husband’s grave” (c. 1830s-1840s) by Wincenty Smokowski

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evening dress 1887-89. Cotton, silk

Via The Met https://bit.ly/3uvKscG

948 notes

·

View notes