Photo

Hong Kong to kill 2,000 hamsters because of suspected animal-to-human coronavirus transmission

By Shibani Mahtani and Theodora Yu

January 18, 2022

Hong Kong has asked pet shops and owners to hand over close to 2,000 hamsters for culling by authorities, after 11 of the small rodents tested positive for the coronavirus in a pet shop. The territory has also suspended the import of small animals.

Authorities announced the decision Tuesday after the city’s health experts found two groups of hamsters, which originated in the Netherlands and arrived in Hong Kong on Dec. 22 and Jan. 7, to be “high-risk” for carrying the novel coronavirus. The hamsters turned over by pet owners will be killed to “cut the transmission chain,” health officials said.

“Evidence shows that the hamsters are infected with the covid-19 virus. It is impossible to quarantine and observe each of them and their incubation period could be long,” said Leung Siu-fai, the director of Hong Kong’s Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department.

Hong Kong had a year to vaccinate its elderly. As omicron spreads, low uptake has left them vulnerable.

The role of pets in coronavirus transmission has been studied and debated since the start of the pandemic, but for the most part, infection appears to be a one-way street, with animals catching the virus from their owners and generally recovering quickly.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called the risk of animals spreading the virus to people “low” but noted that it “can spread from people to animals during close contact.” The exception appears to be minks, with cases of humans being infected by them.

In 2020, Denmark culled some 17 million commercially raised minks after they were found to be at risk of carrying the coronavirus. The government later admitted that the minks were improperly killed and buried, and a commission has been established to look into the case.

In cramped Hong Kong, hamsters have been popular as cute and low-maintenance pets.

The city, like mainland China, is holding firm to a policy of “zero covid,” imposing extreme, 21-day quarantine requirements on anyone arriving from overseas. The territory was able to maintain zero local infections for weeks until December, when two flight attendants returning from the United States who were infected with the highly transmissible omicron variant went out into the community.

Last week, a 23-year-old woman working at a pet shop called Little Boss in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay was found to be infected with the delta variant, which has been rare in the city. At the same time, several hamsters in the pet shop also tested positive for the coronavirus. Health officials in Hong Kong are investigating this as a possible case of animal-to-human transmission because two other human infections, one confirmed and one preliminary, have been linked to the pet store.

Thomas Sit, a veterinarian and assistant director of the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, said that the government did not want to cull all the hamsters but that it was a public health decision.

“You need to realize that the hamsters [which] have already got infected are excreting the virus; they can infect other animals, other hamsters and human beings,” Sit said. “We have to protect public health, and we have no choice.”

Sit added that if investigations found the hamsters were infected during importation, special testing of hamsters would be added before future imports, and the government would gauge other risks for other animals later.

Health authorities have ordered the closure of all pet shops selling hamsters as well as the mandatory testing of anyone who has bought a hamster since Dec. 22.

“We urge all pet owners to observe strict hygiene when handling their pets and cages. Do not kiss or abandon them on the streets,” Leung said.

Animal concern groups immediately expressed outrage at the government’s decision. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Hong Kong said in a Facebook post that it was “shocked and concerned” about the announcement ... which did not take animal welfare and human-animal bonds into consideration.”

Speaking to the local daily the Standard, Sophia Chan, a representative of a hamster concern group, said she has received dozens of calls from hamster owners since the government’s announcement.

Owners told Chan that their relatives were threatening to turn the pets over to the authorities. One hamster owner said that after her family dumped her hamster in their building’s garbage room without telling her, “she had searched through every bag of garbage and still couldn’t locate her pet,” Chan said.

Hong Kong’s government has responded to the most recent coronavirus wave by imposing some of the strictest social distancing and isolation measures adopted since the start of the pandemic here two years ago. Flights from eight countries including the United States and Britain and transit flights from 150 countries are banned, and students have returned to remote learning at home.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Americans adopted millions of dogs during the pandemic. Now what do we do with them?

With the country thrust into uncertainty by the omicron variant, a nation of dog lovers grapples with how to return to ‘normal life’ and care for their pandemic pups

Jacob Bogage

January 7, 2022

Americans face a moment of reckoning with their pandemic pups — and the money they spend on them.

Apollo, a black Labrador in Silver City, N.M., is complicating his owner’s moving budget with his voracious appetite. In Los Angeles, Zuri the Chihuahua mix’s surprise bee allergy has her mom fretting over more unexpected medical bills. In Sacramento, Cowboy the labradoodle’s parents are trying to train him out of his shoe-chewing separation anxiety.

With the country thrust into uncertainty by the omicron variant of the coronavirus, the millions of Americans who welcomed pets into their homes since the first shutdowns in March 2020 are facing shocks to their household budgets and logistical challenges as they try to predict the course of the pandemic and make preparations to return to work and social activities in person.

More than 23 million American households — nearly 1 in 5 nationwide — adopted a pet during the pandemic, according to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). Even President Biden adopted a new dog, Commander.

And many dog owners have spent the pandemic pampering those pooches. Americans spent $21.4 billion on nonmedical pet products through November, plus another $28.4 billion on dog food, according to market research firm Euromonitor International. Rover, a gig-economy platform that focuses on overnight boarding and dog-sitting, reported a record $157.1 million in revenue for the quarter ending Sept. 30.

Now some puppy parents are facing as much as thousands of dollars in additional costs as they prepare to return to life in person.

With many doggy day cares and boarding centers nationwide reporting months-long waiting lists — and newly adopted pets often lacking the socialization for boarding — pandemic pet owners are appealing to families, friends and businesses to ensure their dogs are living their best lives, or at least not spending the day alone. Veterinary practices report being slammed with appointment requests. Vet emergency rooms are warning of longer wait times.

In a pandemic, these pups have made all the difference

Gig-economy dog-walking and boarding platforms Wag and Rover say they have received waves of new customers as different parts of the country emerge from social distancing. So far, Wag CEO Garrett Smallwood said, spending and memberships have followed red state/blue state lines, with Republican-leaning states more likely to open up faster. The newest customers are about 20 percent more active on Wag than customers pre-pandemic, Smallwood told The Washington Post.

“If you had your pet before the pandemic, you had a routine, you knew what you were doing,” Smallwood said. “Whereas, if you adopted your pup during the pandemic, you’re building this routine together now, and you’re learning about leaving your dog alone.”

Danielle Diaz, a county government employee in Silver City, N.M., adopted Apollo, a black Labrador retriever, as a birthday present to herself in July 2020. He was 4 weeks old and he’d been weaned too early. Diaz fed him a paste of puppy food mushed with water when she first got him home, because he wasn’t old enough to eat dry kibble.

Nearly a year and a half later, Apollo is 100 pounds. He eats 12 cups of dog food per day, a $45 40-pound bag of dog food every three weeks.

Adopting Apollo cost $80, Diaz said, an easy investment for a loyal companion. She’s spent probably thousands of dollars more on him since. Day care costs $400 a month. Between food, toys, treats and vet bills — he’s had multiple infections after eating deer and rabbit droppings in the yard — “pretty much all my money, my whole paycheck, goes to him,” Diaz said.

The additional expenses have complicated plans to save for a house with her boyfriend when Diaz finishes graduate school in a couple of years.

“I’ve never sat down and done the math, because I don’t want to know how much it is in total,” Diaz said.

Many dog owners report spending the money saved during the pandemic — from not commuting, going out to eat or taking vacations — on their pets.

Fauci is my dog

Barkbox, the subscription treat and toy service, saw membership increase by 39 percent compared with the same period a year ago, the company told The Post, and revenue increased by 130 percent between April and September compared with the same period in 2020.

Siobhan McKenna, a high school teacher in the Boston suburbs, found a day care run out of the home of a veterinary technician for her Australian shepherd, Smokey, when she returned to in-person work at the start of the 2020 school year.

Compared with other day cares with their own storefronts, this one is much cheaper, she said, but she and her boyfriend still felt they had to cut things out of their budget.

They don’t go out for date nights as much, both to practice caution during the pandemic and to save money for Smokey. McKenna and her boyfriend are cooking at home more, rather than grabbing Chipotle on a weeknight or buying lunch.

McKenna said she hopes to get a dog walker for Smokey this year on the days when her pup does not go to day care. Lately, though, she’s more interested in taking training classes with Smokey for more mental stimulation and to ease separation anxiety.

Others are easing their dogs back in to the day-care routine — and that can be costly.

Dog days

Amy Mercadante, the owner of Affectionate Pet Care, a boarding, grooming and day-care facility in Fairfax City, Va., said some regulars kept up their monthly membership payments during the pandemic, even though they weren’t bringing in their dogs, so their pups could return to a familiar routine when their humans return to work.

In Los Angeles, Janet Kim, who owns the day care Oh Hello Dog, turned her “introduction to day care” training course — basically, How To Be A Dog 101 — into a break-even business and a feeder program to build up her day-care client roster. Her new dog evaluation schedule has a four-week waiting list.

Zuri the 1-year-old Chihuahua mix’s surprise bee allergy upended owner Cheyenne Matthews-Hoffman’s budget the same week of the pup’s adoption, when she swallowed a bee in the backyard.

Within moments, Zuri’s eyes fluttered and she passed out — requiring a trip to the nearest veterinary emergency room. Matthews-Hoffman handed her seven-pound puppy to a vet and bawled, then walked to a nearby Target to buy treats and dog toys.

Zuri emerged two hours later with a healthy strut and a wagging tail. Matthews-Hoffman, a digital content creator in Los Angeles, came out with a $600 bill, which she paid in two installments because she’d already spent hundreds of dollars preparing her home for Zuri’s adoption.

“After I paid that bill, I thought, I have to find a vet that’s not that expensive,” she said. “And was this expensive because it was an emergency, or are all vet appointments like that? I didn’t do any research on how much emergency vet appointments cost. And then I had to research how to get rid of bees in your backyard.”

The lofty cost of such care is not uncommon for people who adopted pets during the pandemic, said Rebecca Axelrad, who runs the nonprofit Buddy’s Healing Paws, which raises money to help pay for emergency veterinary treatment.

Dog owners can budget costs in advance for food and toys and routine vet bills, but that’s harder for emergency medical expenses.

The voices we make when we pretend our dogs can talk

The costs can leave pet owners in an unthinkable position: scrape together the money to care for a suffering animal, or euthanize a creature many people view as part of the family.

“During the pandemic, I’ve had a lot of people reach out to me saying they got a dog or cat during the pandemic but then they lost their job, or their spouse lost their job, or money got tight,” Axelrad said.

Since August 2020, Buddy’s has disbursed more than $20,000, Axelrad said, raising it through online donor campaigns and auctions.

For Matthews-Hoffman, it means saving more. “I’ve kept the mind-set, to make me feel a little bit better, I always think she’s going to exceed however much I’m saving for her, so maybe I should save a little more,” Matthews-Hoffman said about her budget for Zuri. “You literally never know what could happen. What if she’s allergic to something else?”

Changing schedules and separation anxiety

Cowboy the labradoodle is a professional sleeper. He cuddles up to his toys while his human mom, Caroline Cirrincione, works from home outside Sacramento. He sleeps in the car on the way to and from his monthly grooming session. He squeezes in between Cirrincione and her boyfriend on the bed when they go to sleep at night.

He also chews on her shoes.

“All of my Christmas gifts this year were shoes,” Cirrincione said. “I had to do a big overhaul after he ate a few pairs.”

As Cirrincione, who works in advocacy around the California state legislature, spends more time outside the house for work, an anxious Cowboy has fallen into some destructive habits.

He’s learned how to open the closet door to access shoes. Locked in a bedroom once while Cirrincione tried to get him accustomed to being alone, he chewed a hole in the door.

“Everyone says he has the purest intentions, but he’s this massive dog with no boundaries and he chews your shoes,” Cirrincione said. “He knows when he’s done it and it’s wrong, and we’ll look at each other and he’ll look at me like, ‘I’m so sorry I did this.’”

Cirrincione and her boyfriend are experimenting with sending Cowboy to day care as they venture out of the house after getting their vaccine booster shots. They’ve found one that fits their budget but can only send Cowboy a couple of days a week. In the meantime, they’re making more of an effort to bring Cowboy with them on vacation, out to eat or when visiting with friends to cut down on his chances to gnaw on their footwear.

Caitlin Mahoney, a musician and office worker in New York, has leaned on family, neighbors and a hired dog walker for her 2-year-old Chihuahua-cattle dog mix Annie.

Mahoney is fully vaccinated and got a booster shot before Thanksgiving. She is starting to play shows again in New York and thinking about scheduling tour dates — which would probably not be compatible with a canine’s schedule.

In the new year, she is moving to Los Angeles and booking West Coast tour dates for her forthcoming album. She’s in the market for a new dog-sitter.

“It’s been a great joy,” she said, “to learn how to share Annie.”

Best friend and business inspiration

For Sekayi and Farai Fraser of North Potomac, Md., their 20-month-old black Lab, Brock, went from the center of their family’s affection — complete with a raincoat and a Christmas tracksuit that he refuses to wear — to the hub of a growing neighborhood business.

After a family friend offered Sekayi, 16, and Farai, 14, a few dollars to look after their dog for a night, the boys founded “Potomac Pooch Pals.”

They charge $35 a night to check in on a dog at another home or to bring a dog over to spend the night with Brock. The dogs end up tuckering each other out, said the boys’ mother, Mondi Kumbula-Fraser. The extra exercise means Brock needs fewer sessions at day care.

Before the emergence of the omicron variant, Sekayi and Farai were preparing for an uptick in business around Christmastime. By the start of December, they already had four reservations. Then, their booking calendar — and plans to expand their business — were scrambled by increasing infection rates. Both boys are vaccinated, but while omicron rages, taking new clients is difficult. Kumbula-Fraser is wary of other dog owners coming into their home to drop off their pups and of her sons going into others’ homes.

The boys are making plans to sign up new clients as soon as coronavirus cases in their community drop again. They’ve recruited friends from school and around the neighborhood to market their services and walk dogs, too. A cousin promised to advertise in her neighborhood.

There’s one condition, Sekayi said: The dogs must be compatible with Brock. “I don’t want to take any clients that don’t get along with priority numero uno.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Hair-Raising Hypothesis About Rodent Hair

A new paper posits that the guard hairs of rodents and other small mammals may help sense the heat of predators, though more research is needed.

By Cara Giaimo

Dec. 16, 2021

It’s tough out there for a mouse. Outdoors, its enemies lurk on all sides: owls above, snakes below, weasels around the bend. Indoors, a mouse may find itself targeted by broom-wielding humans or bored cats.

Mice compensate with sharp senses of sight, hearing and smell. But they may have another set of tools we’ve overlooked. A paper published last week in Royal Society Open Science details striking similarities between the internal structures of certain small mammal and marsupial hairs and those of man-made optical instruments.

In this paper as well as other unpublished experiments, the author, Ian Baker, a physicist who works in private industry, posits that these hairs may act as heat-sensing “infrared antennae” — further cluing the animals into the presence of warm-blooded predators.

Although much more work is necessary to connect the structure of these hairs to this potential function, the study paints an “intriguing picture,” said Tim Caro, a professor of evolutionary ecology at the University of Bristol in England who was not involved.

Dr. Baker has spent decades working with thermal imaging cameras, which visualize infrared radiation produced by heat. For his employer, the British defense company Leonardo UK Ltd., he researches and designs infrared sensors.

But in his spare time he often takes the cameras to fields and forests near his home in Southampton, England, to film wildlife. Over the years, he has developed an appreciation for “how comfortable animals are in complete darkness,” he said. That led him to wonder about the extent of their sensory powers.

Observations of predator behavior further piqued his interest. While filming and playing back his videos, he noted how cats stack their bodies behind their faces when they’re hunting. He interprets this, he said, as cats “trying to hide their heat” with their cold noses. He has also observed barn owls twisting as they swoop down, perhaps to shield their warmer parts — legs and wingpits — with cooler ones.

Maybe, he thought, “predators have to conceal their infrared to be able to catch a mouse.”

Eventually, these and other musings led Dr. Baker to place mouse hairs under a microscope. As it came into view, he felt a strong sense of familiarity. The guard hair in particular — the bristliest type of mouse hair — contained evenly-spaced bands of pigment that, to Dr. Baker, closely resembled structures that allow optical sensors to tune into specific wavelengths of light.

Thermal cameras, for instance, focus specifically on 10-micron radiation: the slice of the spectrum that most closely corresponds with heat released by living things. By measuring the stripes, Dr. Baker found they were tuned to 10 microns as well — apparently homed in on life’s most common heat signature. “That was my Eureka moment,” he said.

He found the same spacing in the equivalent hairs of a number of other species, including shrews, squirrels, rabbits and a small mousy marsupial called the agile antechinus. The antechinus hair in particular suggested “some really sophisticated optical filtering,” starting with a less sensitive absorber at the top of the hair and ending with patterns at the base that eliminated noise, he said.

As these hairs are distributed evenly around the body, their potential infrared-sensing powers could help a mouse “spot” a cat or owl in any direction, Dr. Baker said.

Dr. Baker’s hunch that these hairs help small mammals perceive predators is “plausible,” said Helmut Schmitz, a researcher at the University of Bonn in Germany who has investigated infrared-detecting mechanisms in fire beetles. (These beetles use organs in their exoskeletons to sense the radiation, which leads them to the recently burned forests where they lay their eggs.)

But jumping straight from structural properties to a biological function is risky, he said. To show that the hairs serve this purpose, it is necessary to prove that the skin cells they’re attached to are able to recognize very small differences in temperature — something that has not been observed, even though these cells have heavily been studied, Dr. Schmitz said.

Dr. Baker has continued to look into this question, designing his own observational tests. (One recent endeavor involves filming how rats respond to “Hot Eyes,” an infrared emitter he built that mimics the eyes of a barn owl.) As these experiments were not controlled, they were not included in the published paper. But now that he has lit this metaphorical torch, Dr. Baker hopes to pass it to others who can look deeper into these anatomical questions, and design more rigorous experiments.

“Animals that operate at night have secrets,” he said. “There must be a huge amount we don’t understand.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I Can’t Stop Wondering What’s Going On Inside My Cat’s HeadAug. 27, 2021

By Farhad Manjoo

Some people keep pets for the cuddles and companionship; it turns out what I enjoy are the philosophical rabbit holes, the sudden tumbles into life’s deepest, most intractable mysteries.

Like, when my new kittens look at me, what do they see? As their provider of food and shelter, do they regard me as a parent? Or, with my towering (relative) size, my powers over light and dark and my apparently infinite supply of cardboard boxes, am I more like a deity to them?

But here I am doing it again — I’m projecting my own human intuition onto my felines. While some behavioral studies suggest cats respond to human social cues and may even like interacting with people, the research also says that there’s wide variation in individual cats’ attitudes. And because cats tend to be far less cooperative with humans’ silly experiments than are dogs, we generally know quite little about what’s happening in their heads. To imagine that my cats spend any time considering my place in their lives might be flattering myself. To them I could be nothing more than a natural resource to exploit, what the beehive is to the honey-loving bear. (See the classic Onion story “Vacationing Woman Thinks Cats Miss Her.”)

I’m getting way ahead of myself. Leo and Luna joined my family almost two months ago. They are 5-month-old Bengal kittens, inseparable siblings who resemble tiny leopards and behave like madcap professional wrestlers with a side gig in street parkour. They are our family’s first pets; we thought they’d be a kind of post-pandemic celebration, though you see how well that has panned out. Yet even with a resurgent virus and this summer’s other disappointments, the kittens have cast a joyous spell over our season.

It’s not only because they are impossibly cute. What I have found magical is the way the kittens help lift my gaze above dreary immediate circumstance. There is a lot going on in the world, a lot of it unpleasant. Watching the cats romp about has become a reliable way to escape all that. I find myself jumping from small questions — does Luna seriously not realize, yet, that she is attached to her tail? — to larger, more abstract and eternal ones: Does Luna even understand that she is — does she, in the way René Descartes conceived it, possess knowledge of a self?

More specifically: What is it like to be my cats? Are they “conscious” in the way I am? What, anyway, is consciousness? And if a cat can be conscious, can a computer?

Yes, these sound like questions one asks when the edible hits. That, though, is my point. Compared with dogs, who have lived with humans for tens of thousands of years and have evolved to read human body language to induce our affection, cats are almost alien in their unanthropomorphizable aloofness. House cats have likely been with humans for less than 10,000 years, and genetically they are little different from cats in the wild. They don’t really even need humans to survive. I think this is what I love about them: Cats are just precisely not-human-enough to confound you, and the confounding is the intoxicating pleasure of them.

Consider the question of a cat’s consciousness. Leo and Luna behave in very ordinary kitteny ways. To them, no hole is too small to explore, no perch too high to aim for, no dangling object too dull to resist. It can often appear as if they are driven mainly by simple, hard-coded instinct and response: IF something moves, THEN pounce. To Descartes, this sort of reflexive behavior suggested that animals were “automata,” essentially mindless machines that lacked the subjective experience of a conscious self.

I’ve been throwing around the term “consciousness” as if everyone knows what I mean, but defining consciousness is actually one of the more difficult aspects of studying it. “Consciousness” is an ambiguous term that refers to an ambiguous concept, the subjective experience of life. The philosopher David Chalmers, one of the subject’s foremost scholars, describes consciousness as a “felt quality” — consciousness is what it feels like to see the sun set or hear a trumpet call or smell the rain on a spring morning.

If this strikes you as vague, you’re not alone. Consciousness has been puzzled over for millenniums, but because it is an internal, subjective experience, merely trying to describe it can hurt your brain. This gets to what Chalmers calls the “hard problem” of consciousness — the mystery over why subjective experience arises out of biological processes, like why when light of a specific wavelength hits your eyeballs you experience the feeling of seeing a shade of vivid red. “Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all?” Chalmers asked in a seminal 1995 paper. “It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does.”

Getting back to my kitties: When they hear me pop open a can of yummy chicken slop and come running and meowing, I sometimes imagine a little dialogue playing out in their furry heads. Perhaps “Food, yay, food, food, now!” or maybe “Chicken, again?!” Descartes would call me crazy for thinking this; to him, the cats are responding only to the sound of the can opening and the smell of the slop, all reflex and no higher-order experience.

Modern scholarship has pretty much undone Descartes’s view. One reason to suspect animals possess consciousness is that we are animals and we possess consciousness — suggesting that creatures with similar evolutionary histories and brain structures, including all mammals, “feel” in similar ways.

There is also evidence that nonmammalian creatures with quite different brain structures possess a conscious self. In 2012, after reviewing research on how animals think, a group of neuroscientists and others who study cognition put out a document declaring animals to be conscious. They wrote that the “weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness,” which they said could likely be found in “nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses.” It is not only possible, then, that my kittens feel the subjective experience of being served chicken slop several times a day — it might be likely that they feel something, even if we have no way of knowing what it is.

Still, I don’t blame you if after all this you’re left asking, Hey, Farhad, I’m glad you like your cats, but why does it matter to anyone what’s playing out in their heads?

I’ll end with a couple thoughts, one slightly obvious and one less so. The obvious reason: Consciousness matters because it confers ethical and moral status. If we agree that our dogs and cats are conscious, then it becomes very difficult to argue that pigs and cows and whales and even catfish and chickens are not. Yet if all these creatures experience consciousness analogous to ours then one has to conclude that our species is engaged in a great moral catastrophe — because in food production facilities all over the world, we routinely treat nonhuman animals as Descartes saw them, as machines without feeling or experience. This view lets us inflict any torture necessary for productive efficiency.

The other reason to contemplate a cat’s consciousness is that we might learn something about those other creatures over which we now hold dominion — robots.

Humanity is presently engaged in a grand effort to transfer many cognitive tasks from humans to machines. Today’s artificial intelligence systems program our social-networking feeds and identify faces in a crowd; in the future, computers may drive us to work, target missiles in war and offer guidance on big decisions in business and life.

Monitoring these machines is already difficult; many A.I. systems are so complex that even the engineers who built them don’t completely understand how they operate. Consciousness would only exacerbate the difficulty. If sufficiently complex A.I. systems could somehow develop consciousness, they might prove more inscrutable and unpredictable than we can now imagine. Not to put too fine a point on it, but depending on the powers we grant them, conscious A.I. could go full Terminator on us.

Machine consciousness may strike you as an absurd proposition. But consider that we have no real understanding of how consciousness comes about, nor any real way of detecting and measuring consciousness in anyone beyond ourselves. Given how little we know about the phenomenon, it would be myopic to suppose that machines could never attain consciousness — as naïve as it was for Descartes to conclude that animals aren’t conscious.

Do you need pet cats to begin to ask these questions? Of course not. It sure helps, though. Before Leo and Luna arrived in my home, I rarely had occasion to consider the inner lives of nonhumans. But cats are a trip; in their everyday, ordinary strangeness, they seem to demand you puzzle out why they’re doing what they’re doing.

You might never solve these riddles; cats don’t give up their secrets easily. But the challenge is why I’m a cat person rather than a dog person. Dogs — they’re just like us! They present little mystery. Cats are the more cerebral companion. The fun is figuring them out.

0 notes

Photo

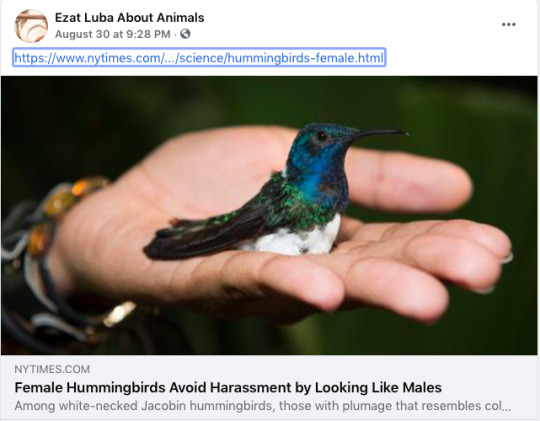

Female Hummingbirds Avoid Harassment by Looking Like Males

Among white-necked Jacobin hummingbirds, those with plumage that resembles colors found on males get harassed less.

By Sabrina Imbler

Aug. 26, 2021

Sign up for Science Times Get stories that capture the wonders of nature, the cosmos and the human body. Get it sent to your inbox.

An adult female white-necked Jacobin hummingbird is no stranger to invisible labor.

When she lays an egg, the male hummingbird who played an equal role in the conception of said egg is nowhere to be seen. It is only thanks to her hours of weaving that the egg has a nest at all. When her chick hatches, she alone will feed it regurgitated food from her long bill.

And then there is the constant harassment. As the muted-green females visit flowers to sip on nectar, they are chased, pecked at and body-slammed by aggressive males of their species, whose heads are a flamboyant blue.

But some female white-necked Jacobins, which are found from Mexico to Brazil, have a trick up their wing: Instead of garbing themselves in green plumage, they take on bright blue ornamentation and appear essentially identical to male hummingbirds. Scientists found these male look-alikes avoid harassment directed toward green females, according to a paper published Thursday in the journal Current Biology.

For the last 50 years, most scientists have relied on the theory of sexual selection, or mate choice, to explain why so many male birds have such foppish traits, such as a peacock’s mirage of tail-feathers or a hummingbird’s sapphire blue head, said Jay Falk, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington and an author of the paper. Dr. Falk led the research on the paper as a graduate student at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and while working with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

But these theories can disintegrate when applied to female birds, which can evolve ornamentation of their own for evolutionary advantages that have nothing to do with seeking male mates.

“If we focus too much on males and sexual selection we inevitably miss the big picture and fail to provide a comprehensive view of nature,” Dr. Falk said. In his eyes, the antidote is social selection: a theory that considers the social lives of the whole species as a driving factor in evolution.

“The assumption that these extravagant traits have to do with sexual selection is something that requires testing,” said Kimberly Rosvall, a biologist at Indiana University, Bloomington, who was not involved with Dr. Falk’s research. “Females compete in all sorts of contexts but only some of those have anything to do with competition for mates.”

The white-necked Jacobin weighs as much as a nickel and a penny, and males grow as long as a toilet paper roll. The birds are also hams, often tail-fanning and back flipping to show off. Dr. Falk calls them “the jocks of the hummingbird world.”

But their varying colors among females are a long-running mystery. During his studies, Dr. Falk came across a paper published in 1950 describing a mélange of white-necked female Jacobin hummingbirds. Some were green, but others were so convincingly male that the original collectors had underlined the symbol ♀ twice for emphasis next to one blue-headed female specimen.

In 2015, to investigate why the female Jacobins resembled males, Dr. Falk went to the town of Gamboa, Panama, one of the hummingbirds’ more accessible haunts.

After sexing 401 birds that visited feeders placed around town and in a nearby forest, Dr. Falk found that around 28 percent of all females resembled the blue-headed males. More specifically, all the young females had the flashy blue plumage of males, while ornamentation tapered to 20 percent of adult females. So all the juvenile birds looked like males, but as the females grew up most molted into a muted green.

The discovery of the male-like juveniles did not align with the idea of sexual selection.

“They’re wearing this beautiful ornamentation when they don’t care about mates at all,” Dr. Falk said.

Dr. Falk wanted to see how the Jacobins would react to the green birds and the flashy blue birds. He painted clay mounts in the style of the birds, but the birds were not moved — artistically or sexually. So he turned to taxidermied mounts, placing combinations of green females, blue males and blue females on feeders to see how passing hummingbirds would react.

If sexual selection were at play, Dr. Falk hypothesized that the male hummingbirds would prefer the flashy, male-like females. But the males had a clear sexual preference for green females. And the Jacobins as well as other species of birds more often directed territorial aggression toward the green females than blue females and males, regardless of the mount’s sex, although they don’t know why.

These experiments matched up with the researchers’ footage of white-necked Jacobin chases in the wild, which revealed green females were chased more than 10 times as often as their blue-headed kin.

The blue-headed females clearly enjoyed more personal space, but were there other benefits? To test this, Dr. Falk monitored the feeding behaviors of green females, blue-headed females and blue-headed males using implanted tracking tags. An analysis of 88,000 feeding visits over nine months revealed the blue-headed females visited feeders more frequently and for longer spells of time than green females.

Forget males; food seems to be the ultimate driver of female ornamentation in white-necked Jacobin hummingbirds. The blue-headed females feed longer and are chased less — a boon for a bird that burns through energy like no other.

“Hummingbirds live on the margins energetically,” Dr. Rosvall said. “An ever-so-slight advantage in acquiring food is a real advantage.”

The question of how, exactly, some females stick with their male coloration remains a mystery. Dr. Falk said he hoped to investigate the mechanism behind this plumage.

If you see a green Jacobin and a blue-headed Jacobin in the wild, they might appear to be a mating pair. But they could also be two females, going about their days quite unbothered by everyone’s assumptions.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Baby bats babble like human infants

Repeated vocalizations could help young bats to practise the sounds they will need as adults.

A greater sac-winged bat (Saccopteryx bilineata) pup babbling. Researchers think the young bats make these sounds to practise their vocal skills.

Pups of the greater sac-winged bat develop their vocal skills by babbling in a similar way to human babies — a discovery that could help researchers to explore the underlying neuroscience of how mammals learn to communicate with one another.

“Even though there are millions of years of different evolutionary pathways between bats and humans, it’s astonishing to see such a similar vocal practice behaviour leading to the same result — acquiring a large vocal repertoire,” says Ahana Fernandez, an animal behavioural ecologist at the Berlin Museum of Natural History and a co-author of the study, which was published on 19 August in Science.

Sat-nav neurons tell bats where to go

Human babies babble to practise speech sounds, which require precise motor control over their voice boxes, research suggests. Young songbirds also babble, but there are very few other recorded examples of babbling behaviour among animals — the bat research is the first to identify baby babble produced by a mammal that isn’t a primate. Like humans, bats need extraordinary control over their vocal apparatus, because they rely on their calls to navigate and find food through echolocation, and to communicate during courtship and mating, says Fernandez.

To understand how greater sac-winged bat (Saccopteryx bilineata) pups learn to communicate, Fernandez and her colleagues recorded 216 babbling bouts in 20 wild bat pups in Costa Rica and Panama. The researchers used ultrasonic sound equipment to capture the individual ‘syllables’ of the pups’ high-pitched squeals, and identified most of the 25 different syllables heard in the vocal repertoire of adult bats.

The team converted these audio snippets into images called spectrograms that show the pitch and intensity of the sound over time. This enabled them to search for eight key features that characterize babbling in human babies, including repetition of syllables and rhythm in the sounds. Their analysis found that the bats’ babble had all eight of these features.

Surprisingly, both male and female bats learnt and produced the syllables that make up the adult male territorial song. The females might use their experience in producing these sounds to help them make mating decisions later in life, the authors suggest.

“It’s interesting to see the similarities in babbling between bats and humans, given the differences between human language and how bats use their vocalizations,” says Jill Soha, an ethologist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who studies vocal development in songbirds. The researchers analysed an “impressive number of syllables” without disturbing the bats, she adds.

Mirjam Knörnschild, an animal behavioural ecologist at the Berlin Museum of Natural History and a co-author of the study, accidentally discovered the bats’ babbling behaviour more than 17 years ago, when she was working on her master’s degree thesis. “You hear these bats and you immediately think of [human] babies,” she says. Although she and her colleagues reported these findings in 2006, some scientists were sceptical that the sounds represented true babbling. The new comparison of the bat pups’ vocalizations with those of human infants should put those doubts to rest, Knörnschild says.

Analysing the bat pups’ brains could help researchers to study the fundamental processes involved in vocal learning, she adds. “These bats are basically waving a red flag, telling us, ‘I am learning right now!’” Knörnschild says. “That means we can ask questions like: what’s going on in the brain while the bat is babbling? Or, what sort of environment do they need to learn better?”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bears, baboons, tigers are getting COVID vaccines at zoos across the U.S.

Here’s what you should know about the experimental COVID-19 vaccine rolling out to zoo animals—and why your pets aren’t getting it.

A chimpanzee examines an toy at California’s Oakland Zoo in April 2020. The ape is one of 48 animals at the zoo to receive a COVID-19 vaccine made exclusively for animals. Thousands more doses are rolling out to zoos, research institutions, and sanctuaries around the United States.

BYNATASHA DALY

AUGUST 20, 2021

Kern the brown bear got his COVID-19 vaccine on July 21. Then he ate whipped cream straight from the can.

Along with their vaccines, the tigers got their favorite meat—beef tenderloin—on shish kebab skewers, and a spritz of goat milk in their mouths. The siamangs—big black-furred gibbons—each got a large marshmallow. The baboons: gummy fruit snacks and a (peeled) hard-boiled egg.

At the Oakland Zoo, in California, 48 animals—including hyenas, chimpanzees, and mountain lions—have received at least one dose of an experimental COVID-19 vaccine made exclusively for animals. Half are already fully vaccinated.

The Oakland Zoo is among dozens of zoos, research institutions, and sanctuaries that have requested the vaccines from veterinary pharmaceutical company Zoetis. The requests came in the wake of news that great apes at the San Diego Zoo became the first zoo animals in the country to receive the vaccines; that was in February, as first reported by National Geographic.

“The story sparked interest from so many of the other zoos, and that’s what led to our big donation plans,” says Mahesh Kumar, senior vice president of global biologics at Zoetis, which developed the vaccine.

Those plans include fulfilling requests to send some 11,000 doses of the animal vaccine to more than 80 institutions in 27 states for free. It’s a promising development for zoo animals, which are at risk of the disease because of their proximity to humans.

But much remains unknown. How effective will the vaccines be? Will they protect animals against the Delta variant? Will the rollout be complicated by anti-vaxxers’ loud objections? And will pets ever need to be vaccinated? The scientists and institutions at the heart of the animal vaccine rollout hope to find answers in the coming months.

Why vaccinate zoo animals?

Since early in the pandemic, zoo animals have contracted the virus. First, tigers and lions at the Bronx Zoo in April 2020; later, a gorilla troop at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. In June 2021, two lions died at a zoo in India after testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have such a large spectrum of animals to care for, from little poison dart frogs to elephants,” says Alex Herman, vice president of veterinary services at the Oakland Zoo.

Although the Oakland Zoo hasn’t detected symptoms of COVID-19 in its animals, “we knew our animals were at risk,” Herman says. Her staff are all fully vaccinated, but “we don’t know how severe Delta will be” or the risk of transmission to animals, she says.

“This virus originated in animals and spread to people, and we know it can be spread back to animals,” adds Nadine Lamberski, chief conservation and wildlife health officer at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. In addition to wanting to keep more of the San Diego Zoo animals safe, “we wanted to do our best to interrupt that [transmission] cycle to prevent the virus from sticking around.”

Getting an experimental vaccine to zoos

After a dog tested positive for the virus in Hong Kong in February 2020—the first reported case in a domesticated animal—Zoetis began developing a COVID-19 vaccine for dogs and cats. By October 2020 the pharmaceutical company had confidence it was safe and effective in both species.

The experimental vaccine, Kumar says, works similarly to the Novavax vaccine for humans, which is currently in large-scale efficacy tests. Instead of using mRNA (like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines), a viral vector (like the Johnson & Johnson vaccine), or a live virus, it uses synthetic spike proteins to trigger the same antibodies the live virus would. (Here’s the latest on COVID-19 vaccines.)

The vaccines are being distributed to zoos on an experimental basis. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is not considering commercial approval of any vaccines for animals, with the exception of mink on fur farms where outbreaks have spread widely, Kumar says. (At least 12,000 mink have died from COVID-19 on fur farms in the U.S. alone and are believed to have transmitted the virus to humans in some cases.)

Prior to each shipment, Zoetis must get case-by-case approval from both the USDA and the state veterinarian where the zoo is located. “There’s a lot of work,” says Kumar, who is overseeing 80 individual [zoo] agreements and 80 individual requests to the USDA and state veterinarians. So far, Zoetis has completed the process for 15 zoos and sent out about 2,000 doses.

The company has received many requests from zoos and other facilities internationally, but the added logistics of navigating various countries’ regulations will be a challenge, Kumar says. For now, they’re focused on U.S. zoos.

Deciding which animals get the vaccine

A year and a half into the pandemic, scientists still know little about how the virus affects non-human animals. Some studies have identified species that may be at heightened risk. In many cases, the veterinary community must rely on limited data sets, learning what it can from individual clinical cases and sporadic outbreaks in a handful of species.

Both the San Diego Zoo and Oakland Zoo requested vaccines for all of their primates and carnivorans—a group of animals that includes big cats, bears, hyenas, ferrets, and mink, among others. These animals are known to be susceptible to the virus, but aside from the deaths of the two lions in India, the majority of big cats and primates have had only minor respiratory symptoms and have made full recoveries.

At the San Diego Zoo and the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, 266 animals have received at least one dose of the vaccine. None of the animals there or at the Oakland Zoo have shown any side effects, according to Lamberski and Herman.

Harley the hyena gets her COVID-19 vaccine at the Oakland Zoo on July 8. She enjoyed eating favorite treat—deer ribs—while veterinarians gave her the shot.

Animal anti-vaxxers

After the Oakland Zoo announced plans to vaccinate some of its animals, it immediately faced backlash from anti-vaxxers on social media, by phone, and by email. Anti-vaxxer Instagram influencers with tens of thousands of followers helped amplify the attacks.

“It was such an onslaught,” says Erin Harrison, vice president of marketing and communications at the Oakland Zoo. “Saying you’re poisoning your animals, killing your animals.”

Many of the messages, filled with misinformation, took the fact that the vaccine is legally defined as experimental to be an indication that zoos were conducting experiments on their animals. “Half of them said we’re going to report you to PETA,” Harrison says.

PETA, for its part, then put out a statement in support of the Oakland Zoo, noting, “These vaccines have been clinically tested and administered to animals only after deep consideration by veterinary professionals. Since growing numbers of big cats, apes, and otters in zoos are contracting SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—from asymptomatic humans, the evidence clearly indicates that the benefits of vaccination in susceptible species far outweigh the dire risks of infection for unvaccinated animals.”

The Oakland and San Diego zoos plan to do antibody testing of the vaccinated animals and share the results with the zoological community to build a database that can help determine the vaccine’s efficacy in various species.

Why zoo animals are getting COVID-19 vaccines and your pet isn't

Although dogs and cats have tested positive for COVID-19 in a smattering of cases around the world, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) don’t recommend vaccinating pets, due to their relatively mild clinical signs and the lack of evidence that pets can transmit the virus to humans.

“It remains our opinion that there is no need for owners to consider vaccinating their pets against SARS-CoV-2 at this time,” notes WSAVA in an April 29 report. (Michael Lappin, chairperson of WSAVA’s One Health Committee, confirms that WSAVA’s opinion has not changed.)

Between zoo visitors and animal caretakers, the chances of a zoo animal getting exposed to the virus is higher, Zoetis’s Kumar says. When compared to lions and tigers, “I wouldn’t say that [domestic] cats are less susceptible—just that the cat is getting exposed to people probably a lot less.”

Any request to vaccinate a cat or dog would have to go through the same process as vaccine requests for zoo animals, with individual approval from the USDA and state veterinarian. “You can imagine if we got 100,000 requests for cats and dogs. So it’s not a practical way for us to supply it,” says Kumar.

Vaccinations for cats and dogs would depend on the government soliciting and authorizing broad commercial use, he says. The USDA is currently only accepting applications for animal COVID-19 vaccines for mink, so unless that changes, the Zoetis vaccine will only be available for other species on an experimental, case-by-case basis.

“The best way to prevent [COVID-19] in dogs and cats is not to let their people become infected,” says Lappin. In other words, Kumar says to pet owners, “vaccinate yourself.”

0 notes

Photo

Killer whales form killer friendships, new drone footage suggests

Cetacean “social touching” rivals that of some primates

17 JUN 2021

BYCHRISTA LESTÉ-LASSERRE

In the animal kingdom, killer whales are social stars: They travel in extended, varied family groups, care for grandchildren after menopause, and even imitate human speech. Now, marine biologists are adding one more behavior to the list: forming fast friendships. A new study suggests the whales rival chimpanzees, macaques, and even humans when it comes to the kinds of "social touching" that indicates strong bonds.

The study marks "a very important contribution to the field" of social behavior in dolphins and whales, says José Zamorano-Abramson, a comparative psychologist at the Complutense University of Madrid who wasn't involved in the work. "These new images show lots of touching of many different types, probably related to different kinds of emotions, much like the complex social dynamics we see in great apes."

Audio and video recordings have shown how some marine mammals maintain social structures—including male dolphins that learn the "names" of close allies. But there is little footage of wild killer whales—which hunt and play in open water. Although the whales only swim at about 6 kilometers per hour, it's hard to fully observe them from boats, and they might not act naturally near humans, Zamorano-Abramson says.

That's where drone technology came swooping in. Michael Weiss, a behavioral ecologist at the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, Washington, teamed up with colleagues to launch unmanned drones from their 6.5-meter motorboat and from the shores of the northern Pacific Ocean, flying them 30 to 120 meters above a pod of 22 southern resident killer whales. That was high enough to respect federal aviation requirements—and not bother the whales. They logged 10 hours of footage over a 10-day period, marking the first time drones have been used to study friendly physical contacts in any cetacean.

To their surprise, the researchers recorded more than 800 instances of physical contact between individuals, they report this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Those included slippery hugs, back-to-back and nose-to-nose rubs, and "flipper slaps" between pairs of whales, all dispersed around bouts of leaping out of the water in perfect synchrony. Other whales playfully tossed calves into the air, letting them splash back into the water next to them.

Those interactions weren't just random, Weiss says. The drone images revealed clear preferences among individuals, usually for one "best friend" of the same sex and age. Take J49 and J51—two distantly related young males ages 9 and 6—for instance. "Every time you see a group of whales, those two are right there interacting with each other," Weiss says. "I wouldn't hesitate to use the word friendship here."

These rates of social interaction paralleled those seen in humans and nonhuman primates. "They're making friends and reinforcing that bond with all this physical contact," Weiss says. "We suspected killer whales were supertactile, but even we were surprised with how tactile they [actually] are." The researchers also noted more than 1600 instances of synchronized jumping and breathing, behaviors that imply social cooperation, he adds.

The youngsters led most of these interactions, rather than older females or males. That runs contrary to a body of evidence showing older females' central role in pods. Older males in particular were more "peripheral," Weiss says. "The young individuals really seem to be the glue holding the groups together."

This gradual loss of "centrality" as individuals age is known in many social mammals, including humans, and suggests a "kind of decline in sociality," Weiss says. "One hypothesis is that as animals senesce, they are less able to engage in social interactions."

That finding is "especially intriguing" for biological anthropologist Stacey Tecot at the University of Arizona, who wasn't involved in the study. Scientists have long observed this "social aging" trend in primates, but "there are still a lot of unanswered questions," she says. She hopes for more footage of the whales to learn more.

And that's certainly on the researchers' radar. "We're already gathering new data, with more advanced equipment," says Weiss, speaking from San Juan Island's Snug Harbor, where his team just moored its boat for the night. "This study is just one piece of a much bigger movement to study different aspects of behavior in marine mammals."

0 notes

Photo

Dog adoptions and sales soar during the pandemic

Shelters, rescues and breeders report increased demand as Americans try to fill voids with canine companion

By Kim Kavin

August 12, 2020

The Cabbage Patch Kids craze of 1985. The Tickle Me Elmo mania of 1996. To understand what has been happening with the sales and adoptions of real, live puppies and dogs during the novel coronavirus pandemic, you have to think back to buying frenzies that consumed the consciousness of the entire nation.

“Within my circle of friends, there are at least five people who have gotten a puppy,” says Tess Karaskevicus, a schoolteacher from Springfield, Va., whose boxer puppy, Koda, joined her family on May 28. “It’s been great. We’ve been having friends come over and play with the puppy while we socially distance. They’re getting a puppy dosage of happiness. It’s been really amazing.”

What began in mid-March as a sudden surge in demand had, as of mid-July, become a bona fide sales boom. Shelters, nonprofit rescues, private breeders, pet stores — all reported more consumer demand than there were dogs and puppies to fill it. Some rescues were reporting dozens of applications for individual dogs. Some breeders were reporting waiting lists well into 2021. Americans kept trying to fill voids with canine companions, either because they were stuck working from home with children who needed something to do, or had no work and lots of free time, or felt lonely with no way to socialize.

At the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Los Angeles, a nonprofit shelter, adoptions were double their usual rate in late June, with 10 or 13 adoptions a day, president Madeline Bernstein said. A waiting list had formed for certain types of dogs, and for puppies in general, because so few were left in the shelter.

“My inventory is low,” she said. “All the shelters are in the same boat, but people still want to adopt.”

Bernstein saw the continuing demand as a second wave happening within the coronavirus crisis. The first wave, when the virus initially struck, consisted of people fostering and adopting in part to help clear the shelters before they had to shut down. Months later, she said, a different type of adopter has come forward.

“There’s been a realization that this is going to go on for a while,” she said. “People will not be getting on planes to travel. They’re going to plan staycations or driving vacations that are more amenable to pets. So they’ll adopt now. This is like a second group of people on a whole other timeline.”

On the other side of the country, at Animal Care Centers of NYC, about 25 percent of the people who agreed to take in foster dogs temporarily at the start of the pandemic had adopted them permanently by late June. Usually, that foster-turned-adopter figure is 10 percent, said Katy Hansen, director of marketing and communications.

And the New York shelter was seeing lower-than-usual return rates on adopted dogs, she added. More adoptions may be working out, she said, in part because of the way the virus forced shelters to change their processes. There have always been pre-adoption forms to fill out in most parts of the country, along with things like home checks and reference calls to verify adopters’ information — some adopters have joked in the past that it’s easier to bring home a child than a dog. Now there are more virtual touch points added to the pre-adoption process.

“There’s so much more interaction with the shelters before the adoption,” Hansen said. “You’re getting people who have found the animal on your website or on social media, have seen the video, read the bio, sent the email, asked for more information, then we do the virtual meet-and-greet — there’s a lot more interaction before the adoption happens. It shows that the person is really invested.”

Breeders, too, reported unusual levels of business continuing into midsummer. Hank Grosenbacher, a breeder of Pembroke Welsh corgis who owns the Heartland Sales auction in Cabool, Mo. — where commercially licensed breeders often buy and sell dogs as breeding stock — said that as of late June, some breeders were investing more heavily than usual in puppies they could raise into breeding-age dogs. Other breeders were reporting pet stores buying full litters of puppies that hadn’t been born yet, putting the money down in advance just to try to keep inventory in the pipeline going forward.

“That means everyone thinks this boom will go on at least another 60 to 90 days,” Grosenbacher said. “For most breeders, business is the best it’s ever been.”

Joe Watson, CEO of Petland, which operates dozens of pet stores in the United States, says demand was so strong in May and June that the breeders the company usually works with saw a flood of new buyers for puppies.

“Demand for all pets were strong in May and June and continues thus far,” Watson said in mid-July.

Many consumers caught in the demand crunch have found themselves navigating the shopper’s equivalent of an obstacle course to bring home a dog from any type of source.

Natalia Neerdaels, a scientist from Sea Ranch, Calif., tried for weeks to adopt a dog from a rescue group while she and her husband, who is in the tech business, were both working from home alongside their 11-year-old daughter. Neerdaels said she contacted nonprofit groups from the San Francisco Bay area all the way up the West Coast to Oregon. All of them were overwhelmed with applications.

“The majority, when I got a reply, said they just didn’t have enough dogs,” Neerdaels said. “They said: ‘You’re too late. Don’t even leave your name.’”

She ended up paying $1,375 for a toy poodle puppy on Craigslist. The family named her Cala Lili.

“She’s now 11 weeks old, and she’s wonderful,” Neerdaels said. “We are very happy. I had wanted to help a dog, to rescue, but it wasn’t possible.”

Ginger Mitchell of Grand Junction, Colo., also came up empty in her initial search. She could find larger dogs in her state’s shelters, but the 68-year-old retiree didn’t want a German shepherd or pit bull.

She turned to the Internet, too, and found a 3-year-old, 15-pound terrier mix named Sammy on the PetSmart Charities website, which features adoptable dogs from around the country. Sammy was in San Antonio with a nonprofit organization called CareTX Rescue.

“This was in early April, and the airlines were starting to shut everything down,” Mitchell said. “You couldn’t ship a dog on a flight that required a connection. It had to be nonstop. There were no nonstops from San Antonio, so these lovely people drove Sammy and some other dogs about five hours to Dallas-Fort Worth. They were supposed to ship him here to Grand Junction on a direct flight from there, but both flights were canceled. We ended up having to drive four hours over the mountains to Denver. It was in the 20s, and there was snow on the ground. It took four attempts to get him to us.”

Sammy was traumatized from the journey, Mitchell said, but soon settled in with her and her husband, who is also retired.

“We had a lot of time to spend with him and bond,” she said. “If not for the pandemic, we’d probably be traveling.”

Karaskevicus, who got her boxer puppy from a breeder her family knew, said her only worry now is about what will happen with the upcoming school year. Both she and her husband are teachers, and if schools reopen, she wants Koda to be ready for a new daily routine without any people at home.

“I thought we should pretend to go to work every day in the garage or she’d have separation anxiety,” Karaskevicus said. “So we crate trained her, just for like 45 minutes a day, we’ll go in the front yard or grocery shopping just so she can get used to us being away.”

Shelter directors, too, are wondering what will happen as Americans start returning to school and work. Bernstein, in Los Angeles, said there could be an increase in dogs being abandoned, or the dogs may have bonded so much with their families that they’ll keep them forever. Like so many things with the coronavirus, the territory is uncharted. Just as nobody predicted that the start of a pandemic would lead to a buying spree for pet dogs, nobody is quite sure what the end of a pandemic will mean for the pups either.

“While we have general ideas and can make good guesses, we really don’t know how this will turn out,” Bernstein said. “Nobody has ever done this before.”

0 notes

Photo

Our dogs have been there for us. Will we be

there for them when the pandemic ends?

When life returns to normal, we mustn’t abandon our pets to loneliness

Clive D.L. Wynne

Photos by Calla Kessler

Aug. 24, 2020

Dogs did not do well in plagues past. Since at least the Middle Ages, the twin terrors of mad street curs and rampant disease were easily connected in frightened minds during the hot and sticky days of late summer. Men and boys alert to their civic duty grabbed cudgels and brained all the mutts they could find. In London, in 1886, constables had to be equipped with special truncheons when the standard nightstick proved inadequate for the task. In Phoenix, during the 1918 influenza pandemic, the population turned against their dogs when the flu hit town. People killed their own pets, or handed them over to the police if they didn’t have the heart for the work. Police also took responsibility for wiping out strays on the streets.

The novel coronavirus pandemic may be the first in human history for which the modes of transmission were known almost as soon as the disease was identified and while some household pets have been diagnosed with the virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said the risk of animals spreading the virus is low.

In fact, dogs are having a pretty good pandemic.

India has declared the feeding of street dogs, who lost food sources when restaurants and street vendors shut down, an essential service.

In March and April, when much of Europe was under total lockdown, one of the few permissible reasons to leave one’s house was to exercise a four-legged friend. People offered their dogs for rent on social media. One man in northern Spain was caught dragging a stuffed toy on a leash, and another disguised his daughter as a Dalmatian to get out of his apartment. A mayor on the Italian island of Sardinia felt compelled to offer the clarification that to qualify for a walk, the dog “must be alive.”

In the United States, people are crying out for canine companionship. Dogs for adoption remain as scarce as toilet paper was at the start of the pandemic. Shelter intake of dogs has halved, and many centers now have no dogs to offer prospective adopters.

The first pandemic in a century feels like a throwback to the lives and deaths of our ancestors. At the beginning of the 20th century, the top three leading causes of death were all infectious. By that century’s end, none of them were. But we suffer a new scourge: loneliness.

The proportion of people in the United States with no one to go home to has more than doubled in the past century. Solitude doesn’t kill, but it can sap purpose from life, and its negative health impacts have been compared to smoking: It has been called “one of the nation’s most serious public health challenges.”

This is where our canine companions step up. We have fired dogs from most of the jobs they once held. Sheepdogs seldom herd animals to market and the turnspit dogs that used to walk in wheels keeping our mutton evenly roasted are long gone. In place of so much diverse employment, however, our dogs perform one absolutely critical task: They protect us from loneliness.

This calling draws on one of dogs’ most ancient skills: the ability to form strong emotional bonds across species boundaries. Where most animals seek friendships only with their own kind, dogs readily form loving connections with many beings.

We love our dogs for the unconditional affection they bring into our lives. But what becomes of them when this is all over? A clue may be found in the fact that the most commonly reported behavioral issue in pet dogs is labeled “separation anxiety,” which makes it sound like an unreasonable reaction to normal circumstances. It isn’t.

We love dogs for their friendly natures, but then too often we sentence them to endless hours of solitary confinement. This isn’t what dogs were built for. They cannot just be switched off like our other smart gadgets.

Winston Churchill is credited with saying, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.” When this pandemic is finally through, our lives will have been changed in a great many ways — most of which we will have had no control over — but there are habits we can and should change for ourselves. It seems highly likely that many of us will continue to work from home, where we have built a form of life that is much more compatible with our canine companions.

As our opportunities to get out of the house improve, we must not forget the dogs we are leaving behind. Those beings who kept us company during the long months when we were too afraid to venture out now in turn deserve our support in protecting them from loneliness. We should slowly get them back into expecting us to leave the house without them by going off on dogless errands from time to time so that they are not taken too much by surprise when duty and pleasure calls us away without them.

As older habits take us out of the house for a larger portion of the day, we must think about how to provide Fido with company. Remember: Most dogs make friends very easily. You may have a home-working buddy or neighbor who would love to pop over and perhaps take your dog along to a coffee shop. And just because dogs so easily make friends outside their own species does not mean that they cannot have buddies of their own kind. A well-run canine day care may be the ideal protection against doggy despondency.

When we were lonely and afraid and didn’t know where else to turn, our dogs stepped up and gave us the emotional support we so badly needed. So in our new normal, we must pay them back at least some of what they gave us.

0 notes

Photo

How Old Is the Maltese, Really?

Many dog fanciers like to trace their favorite breed to antiquity, but the researchers who study the modern and ancient DNA of dogs have a different perspective.

Musette, a Maltese immortalized in porcelain by the French artist Jean-Baptiste Gille, after a model by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse, circa 1855 to 1868.

By James Gorman

Oct. 4, 2021

“The tiny Maltese,” the American Kennel Club tells us, “has been sitting in the lap of luxury since the Bible was a work in progress.”

This is also the opinion of my friend the Maltese owner (the dog is also my friend), who recently invoked the Greeks and the Romans as early admirers of the breed.

I have these conversations on occasion with people who are devoted to one breed or another and I usually nod and say, well, maybe, sort of. True, Aristotle did praise the proportions of a kind of lap dog described as a Melitaean dog. Scholars debate whether this meant the dog came from Malta, or another island called Melite or Miljet, or maybe a town in Sicily. It was a long time ago, after all. Aristotle also compared the dog to a marten, a member of the weasel family, perhaps because of its size. And yes, the Romans absolutely loved these dogs.

So there is little doubt that there were little white lap dogs 2,000 years ago. The question is whether the modern Maltese breed is directly descended from the pets Romans scratched behind the ears.

I have not mentioned this to the dog herself, who would prefer to remain anonymous because the internet can be vicious. And I doubt she would pay much attention to genealogical intrigue. Her interests, from what I can see, run more toward treats, arrogant and intolerable chipmunks and smelly places to roll around in.

It’s not just Maltese fanciers who are interested in their breed’s ancient roots. Basenjis, Pomeranians, Samoyeds, Salukis, terriers and others have supporters who want to trace the breeds back to ancient times. But the Maltese seemed a good dog to discuss because the historical record is so rich. Obviously the Maltese is an ancient breed. Right?

I brought this question to several of the scientists I turn to when I have dog DNA questions. Is the modern Maltese breed, in fact, ancient? The scientists, you will be shocked to learn, said no. But, as with anything involving dogs and science, it’s complicated.

A couple of points to set the stage. All dogs are descended from the first dogs, just as all humans can trace their ancestry to the first Homo sapiens. None of us, or our dogs, have a more ancient ancestry than any other. What people seem to want to know is whether those ancestors were mutts or nobles, William the Conqueror or one of the conquered, a dog on a lap who got into a portrait, or a dog on the street who got into trouble.

I’m not looking at this from the outside, by the way. I’ve been there myself, digging as deep as I could into the long and honorable history of my cairn terriers and Pomeranians. I’ve also tried to trace my family’s O’Connors and O’Learys and Fallons and Goritzes. (I haven’t found any conquerors yet.) But the idea of valuing genetic purity feels creepy sometimes, even if it is in animals who like to roll in cow pies when they get the chance.

Elaine Ostrander, a dog genomics specialist at the National Institutes of Health, has gone as deep into breed differences and history as any scientist. She said the hunger for old breed ancestry is similar to the desire to reach back to the Mayflower for human antecedents. “We think that way about ourselves. So we think that way about our dogs.”

“The Pharaoh hound people were the first to approach me and ask that question,” she recalled.

“Do our dogs really date back to the time of the Pharaoh?” the breeders asked. Unfortunately not. That breed, Dr. Ostrander said, was “totally recreated by mixing and matching existing breeds” after World War II.

Other breeds were established by picking an existing group of dogs in the Victorian era and classifying them as a breed with a definition that meant only dogs whose names were in a registry or whose ancestors could be identified as being in that registry, fit the breed. And 2,000 years ago, she said, “the concept of a breed did not exist.”

Nor does DNA show any direct line from ancient to modern Maltese. To understand what dog DNA research is all about, it’s worth taking a step back. The genetic markers that Dr. Ostrander and other researchers use in genome comparisons to identify breeds are mostly not the genes that contain the recipe for floppy ears or bent legs or a certain color coat.

They are not seeking a genetic recipe for a Basset hound or beagle, but a way to see how closely related one is to the other. Most DNA in humans and dogs has no known function. Only a portion of a genome makes up actual genes. And repetitive stretches of DNA of unknown purpose, if any, have proven to be useful in comparing groups and individuals. They change more from generation to generation and so offer more variation for scientists to work with in comparing breeds. What researchers develop is a breed fingerprint, but not a blueprint.

Neither Dr. Ostrander nor Heidi Parker, a colleague and collaborator at N.I.H., gave a firm answer on how far back a breed could be traced, but they agreed that it basically depended on how long a breed club had been keeping records, not on what’s in a dog’s DNA. Before that time, breeding was not so regulated.

The genomes of the Maltese, the havanese, the bichon and the Bolognese (the dog not the sauce) are all related, Dr. Parker said. The breeds may have split from a common ancestor a few hundred years ago and that common ancestor may no longer exist, or it might have been closer to one of the breeds than the others. But there’s no DNA line to be traced to the time of Aristotle.

When I asked Greger Larson, of the University of Oxford, who studies ancient and modern DNA of dogs and other animals, whether any breeds date to antiquity, he looked, as best I could tell from his Zoom image, like I had asked him if the Earth might really be flat.

“Breeds have closed breeding lines,” he said. “That’s the idea. Once they get established, you’re not allowed to bring anything into it. And that concept of breeding toward an aesthetic and closing the breeding line — that whole thing is only mid-19th century U.K.”

“I don’t care whether you’re talking about a pug or a New Guinea singing dog or a basenji,” he said. Breeds, by definition, are recent.

There have, however, been lineages of dogs bred to the chase, or the lap, or to herd the sheep, for a long, long time. One such lineage, call it Maltese-adjacent, might be defined as “really small dogs with short legs and they require a lot of attention and people are in love with them,” Dr. Larson said. That lineage was certainly around in ancient Rome.

My friend the Maltese partisan sent me images of old paintings. Mary Queen of Scots has some kind of little dog in a portrait from around 1580, but I have to say it looks more like the ghost of a Papillon than a living Maltese. Queen Elizabeth also has a small dog in a portrait from around the same time, which looks like a little white dog, more or less.

There are lots of others, but I doubt they would qualify for the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. And none of this means that the modern Maltese or any other modern breed is the same as the dogs of antiquity.

“We want to say that our dog is very old in its current form, that it hasn’t been changed,” Dr. Larson said. “Like the Maltese is the Maltese for the last 2,000 years. And that’s just clearly” not true. Although “not true” was not the expression he used.