Photo

#Mew#Comforting Sounds - 9 minute Version#Frengers#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture#Jeg elsker Mews musik#Jeg elsker Mew#Jonas Bjerre har smukke hvalpehundeøjne og jeg kan ikke engang lide hvide fyre!

47 notes

·

View notes

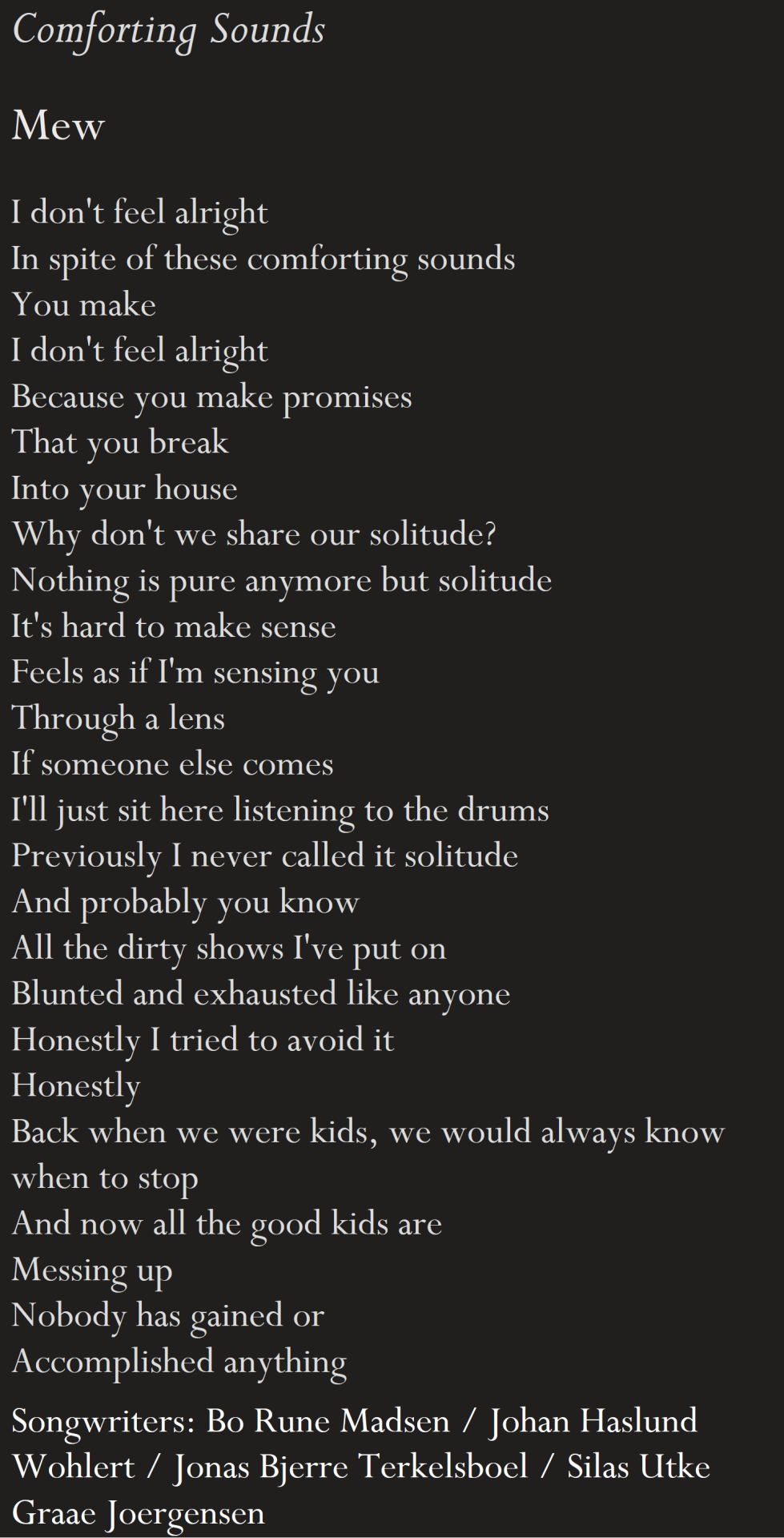

Photo

#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture#Accidental Art#How the fuck did I manage to get this shot!?

0 notes

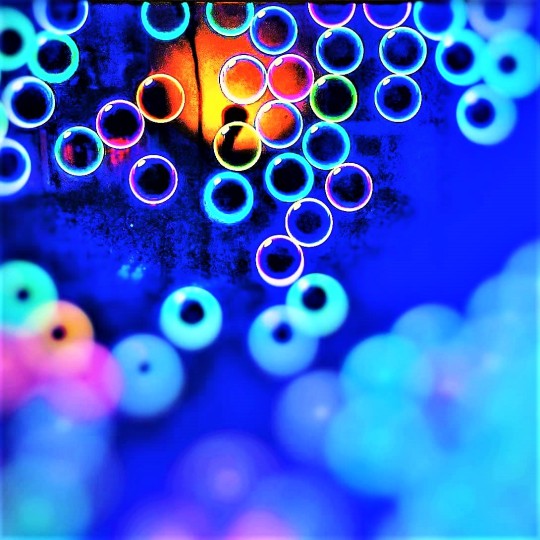

Photo

#The Smiths#Morrissey#Johnny Marr#How Soon Is Now?#I am human and I need to be loved - just like everybody else does#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

would you prefer to learn French or Italian before you die?

the threatening aura of this message reads like it was sent by the duolingo owl

104K notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Archer#Danger Zone!#Slightly-darker black tactical turtleneck#Rampage#Lana-Lana!-LANAAAA! - ---- WHAT!?#Are wenot doing phrasing anymore?#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

0 notes

Text

MY KIA

#KIA CERATO GT Turbo Runway Red#18" Alloy Wheels#7-Speed DCT Transmission#150kW@6000RPM#265Nm@1500-4500#Michelin Pilot Sport 225/40Z R18 Tyres#I Love Cars!#Machine Genders Are Fluid Too!#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

0 notes

Text

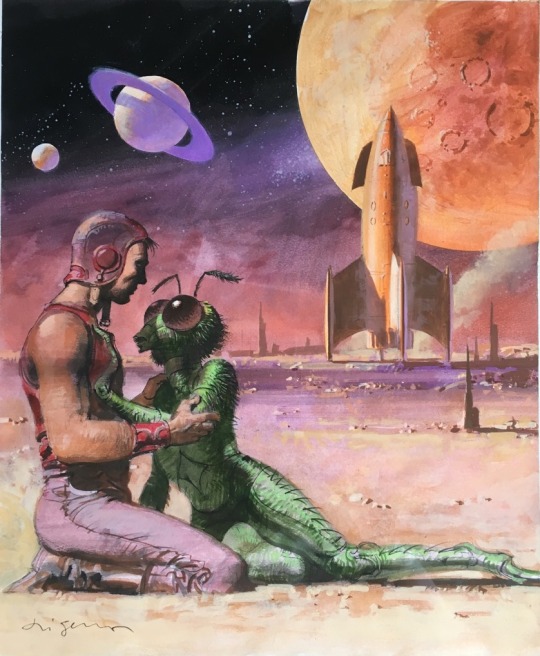

Pulp sci-fi illustration by Italian artist, Aldo Di Gennaro (b. 1938).

100K notes

·

View notes

Photo

0 notes

Photo

#Mew#Snow Brigade#Frengers#2003#Danish Indie-Alternative#Jeg elsker Mews musik!#Mew er mit yndlingsband i hele verden!#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

1 note

·

View note

Text

the thing about being someone who’s never catcalled is that you start to wonder why like is it because im ugly???

and then you realize that youre judging your worth by whether or not you are objectifiable to a man and thats so fucked up like honestly its so fucked up

but the worst part about the patriarchy is that it still sits at the back of your mind regardless like “nobody thinks youre pretty because they dont see you as a sex object” like somehow thats a desirable thing and it fucks me up

345K notes

·

View notes

Photo

SO SAY WE ALL.

stokely always kept it 100

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Manic Street Preachers#If You Tolerate This Then Your Children Will Be Next#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture#British Music is better most of the time!

1 note

·

View note

Text

PROFESSIONAL WRITING - A GOVERNMENT PROPOSAL

A proposal for a Very Fast Train from Brisbane to Melbourne

1. Purpose

This proposal recommends a study into a Very Fast Train network, based on France’s Train à Grande Vitesse to be built, firstly from Melbourne to Sydney. Further lines would then be built from Sydney to Brisbane, and Canberra to Sydney and Melbourne. This would be an important nation-building exercise that would extend Australia’s infrastructure and provide thousands of jobs, and once completed would bring prosperity to the nation and the regions the railway passes through.

2. Key Points

Opportunity

A train trip from Sydney to Melbourne currently takes between eleven and thirteen hours (1). A trip on the TGV of similar distance in France, from Paris to Marseilles, takes between three and a half hours and four and a half hours (2). When considering these differences, the length of time it takes to travel from Sydney to Melbourne by train is simply unacceptable in an advanced country such as Australia. Before we accept the benefits of a high-speed rail network in Australia, we must consider alternative forms of transport such as private vehicles, buses, and aeroplanes and their related costs. A bus from Sydney to Melbourne, in this case Greyhound Buses, which travels via Canberra and costs $99 (3) seems like an excellent choice. The relative economic benefits of this mode of travel are made redundant by the length of time it takes for the journey, a total of twenty-five hours (4). A journey in a private vehicle would take nine hours and would require two full tanks of petrol. At $1.50 per litre and making an approximation that the average vehicle has a tank capacity of fifty-five litres, this comes to a total cost of $165 (5 6). There are ancillary costs involved in driving a motor vehicle, such as tyres, servicing, and the like. This makes driving between Sydney and Melbourne and unattractive prospect. At present, flying from Sydney to Melbourne is the fastest method of travel, taking only one hour and 35 minutes and costing from $130 one way (7). Air travel is beset by security concerns which increase the travel time, plus there are other concerns, such as the possibility of suffering deep vein thrombosis due to the length of time spent sitting in a cramped space with no chance of exercise (8). On a train, passengers can get up and walk around, the seats are generally less cramped than airline seats, and there is the possibility of a train having a dining car which makes high speed rail travel much more acceptable.

Challenges

The greatest challenge to building a high-speed rail network in Australia is the cost. One of the most recent TGV lines-built cost USD$15 million per kilometre, and this included several viaducts and tunnels (9). This would put the cost of a line from Sydney to Melbourne at approximately $18 billion dollars. This is a significant cost and is the project’s greatest challenge. This cost may change depending on how many viaducts and tunnels need to be built to accommodate the line, and these are secondary challenges.

Solution

A fact-finding mission to France, Germany, and Japan should be undertaken to determine whether the TGV is best for Australia. A full report should be generated based on these missions. SNCF, France’s national rail operator should be brought on board to advise in the planning and construction of a high-speed network if the TGV is chosen.

3. Background

The TGV is both a commercial and a technical success (10). Due to increased comfort levels, competitive fares and safety, the TGV has become an unparalleled success story in France, as by the end of 2003, the TGV had carried one billion passengers (11).

4. Audiences and Outcomes

Report — the audience for the report will be the Minister for Transport’s office. The report will address the concerns of the department and lay out all the stakeholders who will be involved in the construction of a high-speed rail network in Australia.

Speech — the audience for the speech will be both the Australian public and the Australian media. The idea is to sell the concept of high-speed rail to the Australian public.

5. Key Messages

Report — High-speed rail is a necessary and vital nation-building project for Australia that will provide thousands of jobs and stimulate the economy.

Speech — Australia can only benefit from a project like this and despite the cost, the positives outweigh the negatives.

6. Structure

Report — The report will be similar in structure to this proposal but will be filled with greater detail and information.

Speech — The speech will be a rousing testament to Australia’s other great nation building projects like the Snowy River Hydro Scheme and a call for Australia to take on a great project that will bring lasting benefits to the country.

Sources:

1. Google Maps, September 2018

2. Google Maps, September 2018

3. Greyhound Australia, https://www.greyhound.com.au/coach-travel/popular-routes/from-new-south-wales/sydney-melbourne/. September 2018

4. Google Maps, September 2018

5. Google Maps, September 2018

6. Here is the cheapest petrol in Sydney. https://www.triplem.com.au/news/sydney/here-is-the-cheapest-petrol-in-sydney?station=sydney. September 2018

7. Google Maps, September 2018

8. Blood Clots and Travel: What You Need to Know. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/travel.html. September 2018

9. French TGV Network Development. http://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr40/f22_ard.html. September 2018

10. French TGV Network Development. http://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr40/f22_ard.html. September 2018

11. French TGV Network Development. http://www.ejrcf.or.jp/jrtr/jrtr40/f22_ard.html. September 2018

#Professional Writing#Mock Government Proposal#Do NOT plagiarise my work - it has been submitted to Turnitin - you will be caught!#Writing Majors don't just compose poems and short stories#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

0 notes

Text

Cyborg Identities – Media and Identity – The Terminator & Terminator 2: Judgement Day

On the internet, we are able to create new cyber-personalities, avatars that bear no resemblance to ourselves, and free ourselves from the constraints of the physical limitations of the real world. You are posthuman, (Becker, 362). Identities are always changing shape, in the same way water takes the shape of whichever containers it fills. This happens in real life (IRL) as well as in the internet domain.

Becker (362) notes theorist Donna Haraway states humans have already become cyborgs, and any delineations between human and machine are evaporating. We should not be afraid. There is nothing to fear. Skynet (Cameron, 1984) is not coming online anytime soon, and no Cyberdyne Systems Model 101 (ibid) is going to come from the future and say “Your clothes. Give them to me,” (ibid). Haraway and Butler state that “gender and sex,” (Becker, 362) are not natural but imposed upon us by particular debates and forced on our bodies by society (362). Haraway notes that our bodies cannot be considered as amalgamated units with delineations and definitive, static identities (362). New models such as computer code, optical, copper, and Wi-Fi networks — the whole global data network, of which the internet is only a part, and the fragmentation of technologies and media, have eliminated the idea that the only thing anyone can be sure of is that they exist, and genuine knowledge of anything else is unachievable (362).

“This is deep!” - John Connor, Terminator 2 (Cameron, 1991).

In the postmodern world, we appear to be living in a situation of overexposure. Telotte notes Jean Baudrillard finds this “obscene” and “everything…immediately transparent, visible, exposed,” (26). Telotte, writing in 1992, thought that true science fiction films echoed Baudrillard’s notes on the overexposure that focused on the synthetic, the “robot, cyborg, android…” (26). These unnatural bodies threaten and frighten us. They make us feel as if we are headed for our own destruction if technologies relating to cyborgs, robots, and androids are left to continue on their current paths (26).

The two Terminator films show a conflict between humans and robots, cyborgs, and machines. Humans have been subjected to nuclear genocide by machines, led by the autonomous defence computer network, known as Skynet. The survivors band together and strike back at Skynet and the machines in the year 2029, in Los Angeles. The Resistance, as they are known, are so successful that Skynet decides to send — first, a cyborg back in time to kill the mother of the leader of the Resistance — and a second, more dangerous, implacable, inexorable Terminator to kill the Resistance leader, John Connor, while he is still a child (Telotte, 26).

The first film The Terminator (Cameron, 1984), shows the cyborg body, a technological threat that plays on society’s fears of what Telotte calls “Technophobia,” (Telotte, 28). The danger is not just for Sarah Connor, played by Linda Hamilton, if she is killed by the Terminator (T1), played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, the future of humanity is at stake (28).

Telotte argues that showing us the “technologized body” as a threat from the T1, plays to a societal fear of “technophobia” (28). The T1 passes easily for a human. He sweats, his skin is shiny and oily, and his first interaction with some punks does not go well. At first, the T1 repeats what the punks say. He is completely naked, and the epitome of hegemonic masculinity. He kills one punk, the rest but one run away. The T1 then says his iconic line: “Your clothes. Give them to me,” (Cameron, 1984).

The T1 is so difficult to “read” that Kyle Reese, played by Michael Biehn — sent back through time by the Resistance, as the protector of Sarah Connor — cannot shoot the T1 in the nightclub, where Sarah is holed up, until the T1 makes his move.

After this shootout, and the following chase, in which Reese is arrested and Sarah gives a statement, the T1 shows up at the police station. He surveys the flimsy structure and says: “I’ll be back,” (Cameron, 1984). He then ploughs a car into the front of the station and massacres police in search for Sarah. Reese and Sarah escape.

The T1 is now shown to be more machine than cyborg. He has a damaged hand that he must repair — he cuts the living tissue off, exposing the metal skeleton — and fixes his damaged hand. His organic eye is irreparably damaged, so the T1 simply cuts out the organic eye covering, exposing the digital video camera he has in place of eyes, (Telotte, 28).

In Terminator 2: Judgement Day (Cameron, 1991), Telotte argues that the T1 is not a threat, but a protector. “Holy shit! My own Terminator, cool!” – John Connor, (Cameron, 1991). Sarah and John remove and alter the cyborg’s CPU so it can begin to learn (29).

Terminator 2: Judgement Day (Cameron, 1991) shows the rehabilitation of one Terminator, but the introduction of a second, more deadly, more unstoppable Terminator — the T-1000, played by Robert Patrick. It has no organic covering, no metallic endoskeleton — it is “all surface,” (Telotte, 29). The T-1000 has no gender, it is a “poly-mimetic alloy,” (Cameron, 1991) that can take on whatever shape it touches. Telotte argues that the T-1000, being all surface and no depth, or inner workings, indicates misleading reassurances that society may feel about the increasing hegemony of technology in our everyday lives (29).

The T-1000 is a genderless, fluid thing. It can form solid metal objects: stabbing weapons, prying tools, and other human beings —both women and men, with near-perfect accuracy. (It does not know John’s dog’s name.) “Your foster parents are already dead,” – The T1, (Cameron, 1991). The T-1000’s formless shape gives rise to a new kind of fear — “what shapes we give to our technological imaginings — and what shapes they could, in turn, give to us,” (Telotte, 30).

Judith Butler states in Performative Acts and Gender Constitution that gender is “not a stable identity,” and gender is “…an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts,” (519). The T1 is the ultimate in male hegemonic masculinity. He is tall, well-muscled, with razor-sharp cheekbones, and a square cut jawline. His appearing naked also showed a shot of his penis, leaving no doubt that this cyborg stands for a masculine gender performance. Once the T1 has the punk’s clothes, and later the iconic image of him wearing sunglasses at night; this repetition of acts that carries over through two films, cements the T1 as the apex of hegemonic masculinity. He performs his gender by wearing punk clothes, by wearing sunglasses, by the use of weapons, by his muscle-bound frame, by his ultra-violence, and by riding a Harley-Davidson in Terminator 2, (Cameron, 1991).

Sarah Connor is an interesting case for her gender performance. As Butler contends; “the body becomes its gender through a series of acts which are renewed, revised, and consolidated through time,” (523). In The Terminator (Cameron, 1984), Sarah is first presented as an example of the opposite of the epitome of the 1984 female. She performs her gender by wearing jeans, riding a motorcycle, and when she is stood up by her off-screen boyfriend, she goes to the movies alone. She ends up in a restaurant, eating pizza, where she discovers, not only that a second Sarah Connor from Los Angeles has been executed, but also a third. When Kyle Reese saves (and kidnaps) her from the T1, and forces her to listen to him, she relents — and becomes passive, “I can’t even balance my check book!” – Sarah Connor, (Cameron, 1984). Later the pair have sex, conceiving John Connor.

By the end of The Terminator (Cameron, 1984), Sarah has changed her gender performativities that have been placed on her by the T1’s inexorable quest to terminate her. After Reese dies to save Sarah, she lures the remnants of the T1 into a hydraulic press. As she presses the button, crushing and destroying the T1, she says in a firm and deep voice: “You’re terminated, motherfucker!” (Cameron, 1984).

Sarah undergoes a dramatic gender performance change in the second film. The first time the viewer sees her, she is sweating, oily-skinned, and doing pull-ups on her upturned bedframe. Not only has she become a cyborg, but also, she has changed her stylised acts of repetition. Sarah has become masculinised in the way she performs her gender. She looks like a Terminator — well-muscled and prone to violence and aggression. She is a weapons expert; she is in Pescadaro State Mental Facility because she was caught trying to blow up a computer factory, (Cameron, 1991).

The T1 performs his gender in much the same way as he did in the first film, except this time he is the protector, not the Terminator. After alteration of the T1’s CPU, he begins to learn — as he is lowered into molten steel, after hugging John and saying “Sorry John, I must go away now,” the T1 says “I know now why you cry,” (Cameron, 1991).

John Connor, played by Edward Furlong, performs his gender in a series of repetitions that become clearer throughout the film. At first, his performativity is that of the rebellious teen — he rides a motorbike and does not listen to his foster parents. In time, it becomes clear that John is compassionate. He discovers that the T1 must obey him, so he commands it not kill people anymore. The T1 now shoots them in the legs: “He’ll live,” says the T1 after shooting a security guard in the leg, (Cameron, 1991).

There is a moment in Terminator 2 where Sarah, fully armed and become a Terminator herself, masculinised and with deadly violent intent — goes to Miles Dyson’s house. Dyson, the inventor of Skynet, is days away from making a breakthrough which will set the future on a course of nuclear annihilation in 1997. At a considerable distance, the Terminator, Sarah Connor, aims an assault rifle with a laser scope at the back of Dyson’s head. She pulls the trigger. Dyson bends down at the last millisecond, and Sarah misses. She switches to fully automatic and begins spraying Dyson’s office with bullets. The magazine is empty, she pulls out an automatic 9mm pistol, and begins firing at Dyson, still a Terminator.

She enters the house and at close range, shoots Dyson through the shoulder. His family come rushing in and his son leaps onto his father. “Please don’t kill my boy,” Dyson begs. Sarah falters. Is she still a Terminator? She is a mother, with a son of her own. She slumps against a wall and begins to cry as John and the T1 enter. John hugs his mother, asks her if she is hurt and she becomes fully human in this moment: “I just couldn’t do it…I just couldn’t…I just couldn’t...I just…” - Sarah Connor says. John holds her tightly as she begins to sob heavily. She is no Terminator. (Cameron, 1991).

Throughout the denouement of the film, Sarah regains and keeps her masculinised gender performance until the T1 is immolated, wherein she hugs the distraught John, in an act of motherly compassion.

Works Cited

Becker, Barbara. "Cyborgs, Agents, and Transhumanists: Crossing Traditional Borders of Body and Identity in the Context of New Technology." Leonardo 33.5 (2000): 361-356. PDF. 16 October 2020. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1576879>.

Butler, Judith. "Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory." Theatre Journal 40.4 (1988): 519-531. 16 October 2020. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/3207893>.

Telotte, J.P. "The Terminator, Terminator 2, & the exposed body." Journal of Popular Film & Television 20.2 (1992): 26-34. PDF. 16 October 2020.

Terminator 2: Judgment Day (Director's Cut). By James Cameron and William Wisher. Dir. James Cameron. Perf. Arnold Schwarzenegger, et al. Prods. James Cameron and Stephanie Austin. TriStar Pictures, 1991. Digital Video. 10 October 2020.

The Terminator. By James Cameron, Gale Anne Hurd and William Wisher. Dir. James Cameron. Perf. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn. Prod. Gale Anne Hurd. Orion Pictures, 1984. Digital Video. 10 October 2020.

#The terminator#Terminator 2: Jugement Day#Academic Paper - submitted to Turnitin - so don't plagiarise it!#I'm trusting Tumblr here#Be good to me#Cyborgs & Identity#Media & Identity#university#Brisbane#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

0 notes

Text

JAKARTA LEGACY

My mental state began to deteriorate when the Australian Embassy was bombed on the 9th September 2004. I was standing on my balcony, eight hundred metres away from the embassy when the bomb went off. The sound was like no other that I have ever heard, it was like a flat smack! The blast wave knocked me backwards against the wall of the balcony.

Foolishly, I decided to have a look at the bomb site. My ex-boyfriend Todo, with whom I had only broken up with about a month before, worked in the embassy in the AUSAID department. I tried to get him on the phone, but it just kept going to voicemail. I was worried about him; I still had some remnants of care from our relationship. When I got there, the scene was carnage. People were walking around aimlessly in a dazed state. Windows within a 500-metre radius were shattered, paper was falling from these jagged openings like rain, cars were destroyed, trees and bushes were shredded, burnt, and stripped of their leaves, and body parts were strewn around the bomb crater.

After about ten minutes, I realised I was going into shock, so I ran back home and called Arman to find out where he was. I was so terrified he had been near the blast. He was on the north side of Jakarta and had not even heard the bomb explode.

I would never have guessed that on my first day in Jakarta I would be leaving in severely deteriorated mental health. My first day in Jakarta was somewhat of a disappointment. My boyfriend at the time, Todo had decided to go to work on my first day in this strange and wondrous — and confusing city, leaving me to my own devices, not speaking a word of Indonesian and not knowing a thing about Jakarta.

I had come to Indonesia because Todo had arranged a job interview with English First, a private English language school. Luckily, I had organised an internet friend to be my tour guide. His name was Jojo and he was extremely cute. He was a little shorter than me, with close cropped hair, kind almond-shaped eyes, and kooky teeth like David Bowie’s. He met me outside the Australian Embassy, we grabbed a taxi, and set off to explore Jakarta.

Jojo took me to the place where the Hotel Indonesia and the Plaza Indonesia sit side by side in a circular formation. Plaza Indonesia is a giant shopping mall with all the Western trappings one might expect to find. Next, we went to Monas – Monumen Nasional, sometime jokingly referred by westerners as “Sukarno’s last erection.” This is chiefly because it resembles a phallus and I’m assured that this is no accident. We climbed all the way to the top and looked out over the city, then we went back down to the museum at the bottom of the monument and took in some of Indonesia’s great history. After this, we went to a karaoke bar on the north side of the city and we sang a few songs and made out like teenagers. The day having been spent, Jojo and I went back to the Australian Embassy where I waited for my boyfriend to finish work.

Todo did not stay my boyfriend for long. I had lived with him in a shitty little boarding house known locally as a kost. These were everywhere in Central Jakarta, some of them cheap and rat-infested and others at the more luxurious end of the scale. Todo was a tightwad and even though I had my own cash, in those first few weeks of being in Jakarta, I had no idea of what to do or where to go — and I couldn’t speak the language yet. So, we lived in one of the shittier kosts. We never went anywhere and never ate out, despite this being a cheap thing to do. He left me to my own devices day after day as he went to work, and I suppose this was kind of a good thing — I got a crash course in Bahasa Indonesia from the other residents of the kost.

One night, Todo took me to a gay nightclub called Two-Faces where he spent the night guard-dogging me against any guys that showed an interest. But that all changed when Arman walked in and we locked eyes from across the room. He managed to sidle his way over to me and sit down next to me. We exchanged pleasantries and he gave me his business card — he was a finance worker for Mitsubishi, and this is the lie I told Todo— that I was interested in buying a car from Arman.

Three weeks later Arman and I were living together in a more upmarket kost where they cleaned your rooms daily and did your laundry, and there was a little café out the front where you could get breakfast. Salted duck eggs, rice, little fish called terasi served with peanuts. It was paradise compared to my previous kost.

My medical troubles in Jakarta began in earnest in September 2004 when I woke up vomiting a chocolate-coloured mess and having no feeling down my left side. As ambulances in Jakarta were mostly for ferrying the dead to graveyards, we had to call a friend who had a car as we didn’t have one at this stage. They were reluctant to help us initially until I shouted down the phone:

“I’ve had a stroke!”

On the way to the hospital, I insisted on smoking several cigarettes as I knew I wouldn’t be able to smoke in hospital. Arman, now my husband, to his credit took a week off work and slept beside my hospital bed every night. I had only known him for three months, so that’s when I knew he was a keeper. With Arman’s help and a lot of effort, I recovered from my stroke and regained the use of my left side. My speech was not affected but to this day, I sometimes transpose letters when I’m handwriting, as I’m left-handed. I credit Arman and my neurologist for my return to health. My neurologist was a fabulous woman in her thirties who had long, red, fake nails and whose lipstick bled through her cloth mask. I got on with her very well and it was her psychiatrist father who treated me later.

The next knock to my mental state occurred when we were living on the top floor of a 46-storey building. Arman was managing a company for his friend in Japan at this point and they had bought an apartment for us. At 02:00 one morning there was a 7.3 earthquake that shook the whole building waking us in fright. We ran all the way down the stairs — 46 storeys that took us over 25 minutes to get to the ground. I suppose you could say that I had PTSD at this stage as I had nightmares and slept poorly, waiting for the next earthquake.

My other medical troubles involved drugs but not illegal drugs. One afternoon after I had finished work, I decided to go to the Rumah Sakit Tebet, which is a typical, small, Christian-run hospital. I went into the emergency waiting room and there was a cliché nurse in a pressed, white uniform. She even had a little white hat on.

“Bisa Bahasa Inggris?” I asked

“Ya, sedikit-sedikit,” she replied

“I’m having a panic attack, I can’t breathe properly, and my heart is racing. Can you please help me?”

“Ok, you wait here,” she said.

I sat down in the waiting room, my legs jiggling and my hands shaking. I waited for what seemed like an eternity, but it was only about twenty minutes. A tall, grey-headed doctor came out and waved me in. He sat me down and asked for my symptoms. I repeated what I had told the nurse, can’t breathe properly, heart racing, I feel panicked. He asked me what I wanted him to do and I said,

“I need some diazepam.”

“Oh, I see. Have you ever had it before?” he asked.

“Yes, I used to be on it when I lived in Australia. It’s essential medication for me.”

“Well, I can give you some tablets today,” he said.

This doctor, this soft touch, became my go-to for my future diazepam needs. I would present at emergency, spin the same yarn about having a panic attack and I always got what I wanted. Sometimes it was diazepam, sometimes it was lorazepam — sometimes I even managed to convince the good doctor to give me a 10mg diazepam injection — which was magnificent, and it eased my troubled mind — at least for a short while.

When this doctor had finally had enough of my histrionics, I went above his head and bribed the doctor in charge of the hospital to continue to supply me with the drugs — it worked, corruption is endemic in Indonesia and it penetrates all levels of society — I craved those chemicals to calm my traumatised mind.

My mental problems grew increasingly worse after another earthquake struck, this one worse — 7.6 in magnitude and only 170 km to the north-west, off the coast of Jakarta. I was in the lift of my apartment building at the time and it began to sway from side to side, smashing into the walls of the elevator shaft as it went up. When I got out of the elevator, I couldn’t stand up because the building was swaying so violently. There were several people there with me and one of them was yelling “Oh Tuhan, oh Tuhan, oh Tuhan,” right in my ear. Tuhan being a cry to god. I couldn’t stand it, so I got up along the wall to my apartment and went inside, smoked three pipes of weed, and lay on the couch until the earthquake subsided — I did not care if the building collapsed — I was on the top floor, and there was absolutely nothing I could do.

It was at this point my mental health took a turn for the worse. I engaged in further drug-seeking behaviour and would often turn up for work under the influence of whatever I could get my hands on — diazepam, morphine, tramadol, gabapentin. No one at work noticed but I was buzzed every day. It was not at all for pleasure; it was self-medicating for the mental trauma I was suffering.

The next brush with death occurred on the 14th July 2009, when Arman and I ate at the Srivijaya buffet room in the J.W. Marriott Hotel in Kuningan, Jakarta. Three days later, on the 17th July, a suicide bomber walked in with a backpack full of explosives and detonated his bombs. At the same moment, another suicide bomber walked into the foyer of the Ritz-Carlton, directly opposite the Marriott, but he was stopped by security, wherein he detonated his bomb. I was quite disconcerted by this experience.

At the time the bombs went off in the Marriott and the Ritz-Carlton, I was teaching a Study In Australia Program (SIAP) to captains and majors in the Indonesian military. The SIAP IELTS program was designed to ready these military personnel to a level of English that would allow them to undertake master’s degrees in counterterrorism and the like at Australian universities. It was a cooperative effort between my school, the Australian Embassy, the Department of Defence, and ABRI, the Indonesian Military.

When we heard the bombs go off; I asked my military students if they knew who was behind the bombings. I was with several majors and captains, smoking outside during a break from class. I had some idea as I had heard talk from my in-school students, some of whom were the children of government workers and big businesspeople.

“I think I know who was behind the bombing,” I said.

“Who do you think it was?” asked one of the majors

“Was it the guy who’s running for vice-president with XXXXXXX?”

“I don’t want you to say that again,” said the major.

“So, am I right?” I asked.

“Please, you can’t talk about this anymore. It is dangerous for you,” he said with finality.

Since then, I have been enduring the weight of knowing who was behind the twin bombings of the Ritz-Carlton and J.W. Marriott Hotels in 2009.

Arman and I decided that it was best if we go and live in Australia, where I could get the medical help I so desperately needed and the support from my family. Arman set out to become a permanent resident of Australia and he had to do this by himself, as I had to work and was of little use.

My mental state began to decline further and people at work noticed there was something wrong with me. I missed a promotion and my reaction was ugly to say the least. I began to act out and soon other teachers noticed my behaviour and would ask me if I was ok. I lied and said I was, but things were deteriorating. My manager called me into his office

“I’m going to get down to it straight away,” he said. “Would you like to take a few weeks off, to get your head right?’

“No,” I shook my head in denial. “No, please. I’m fine. I can still teach. I’m doing my job well, I think. There’s been no complaints.”

“I’ve heard things from the other teachers, they say it sounds like you’re not coping well. Please consider a holiday. I think it’ll be of great benefit.”

“No really, I’m okay. I’m coping well. I really don’t want to take time off. I don’t need it.”

After this, things became so bad that I broke down and cried in a class full of children, who I’m sure were scarred by the experience.

Arman was working hard getting his permanent residency and I became too much to handle. We went to see a psychiatrist, the father of my neurologist, who put me on a raft of psychoactive drugs and then decided that I should be admitted to a psychiatric hospital. It was an odd feeling being in an Indonesian psychiatric hospital, for a start I couldn’t communicate well with the other patients and it was hard interacting with the staff.

I did make one friend — a 19-year-old boy who apparently was suffering from major depression. From my perspective, he seemed like a shy, introverted nineteen-year-old boy, whom I suspected was gay. His parents had admitted him when he failed to thrive at ITB (Institut Teknologi Bnndung) university. He and I would talk every day while we smoked in the outdoor area. I developed a bond with him and after a few days, we were fast friends. He told me all about his inability to cope at university and his parent’s insistence that there was something wrong with him. I strongly believed there was nothing wrong with him at all.

The food was abysmal — sloppy rice with fish and other such tasteless muck. My psychiatrist insisted that I stay in the hospital for three weeks, which did not mesh with Arman’s arrangements for us to go to Australia. He telephoned my parents who in turn telephoned the Australian embassy. They then sent out two consular officials who demanded my immediate release from the hospital. My doctor had no choice but to comply.

Arman had organised everything, his permanent residency, our tickets to Australia and he had arranged for our belongings to be sent via air freight to Brisbane airport. So, I found myself on my way home to Australia doped up to the eyeballs on alprazolam, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, and several other drugs. It was a rough flight home but I’m usually a good flier. I found myself popping 2mg alprazolam every other hour because I could not cope with the panic.

When we arrived home, my parents almost did not recognise me, I knew because I saw their shocked looks. My face was all puffy, I was bloated, I had put on weight and I had dark circles under my eyes. My mum cried when she saw me, so I must have looked a mess. My mum and dad had organised a caravan for us to live in in my sister’s backyard.

It was a dramatic comedown from living on top of one of the tallest buildings in the middle of one of the largest cities in the world.

I began to get proper medical care. I saw a G.P. who referred me to a psychiatrist who then took me off most of the drugs they had put me on in Jakarta. I slowly began to improve but to this day I have Bipolar II Disorder, PTSD, anxiety, and panic, and ADHD – Inattentive Type.

I am on the Disability Support Pension.

This is one side of the legacy of my time in Jakarta. One day, I shall tell the rest of my Jakarta legacy.

©2019 against-a-dark-background

#Jakarta Legacy#Fictional Memoir#Psychotic Break#Self Medication#Drug Misuse#Bipolar II Disorder#PTSD#9th September Australian Embassy Bombing - Jakarta - 2004#2009 JW Marriott & Ritz-Carlton Suicide Bombings#7.5Earthquake while on the 46th floor of an apartment building#Charles' Fictional Memoirs & Sci-Fi & Pop Culture

0 notes